Why Should You Watch Movies With Sound?

Published:

Being born as an “older” Generation Z, I was fortunate to grow up without iPads and smartphones for the first decade of my life. However, kids are naturally drawn to screens; for young me, it was the movie theater.

I’m not sure if you’ve ever been trapped in a highly restrained, dark, noisy, and crowded space for 14 hours straight, but I’m sure you have if you’ve ever flown from Canada to Asia. What made it worse was when the flight attendant cheerfully informed passengers that they no longer provided earphones; apparently, budget cuts had reached new heights at 30,000 feet. That’s how I gained my first thorough understanding of how utterly lifeless a movie can be without sound. Watching Tom Cruise’s lips move silently while he presumably saved the world was, in some sense, more confusing than inspiring.

This experience motivated my exploration into film music. The University of Waterloo offers a fascinating course on soundtracks, taught by professional film score composer Simon Wood. As an avid music history enthusiast, this course not only satisfied my curiosity about film score history, but also revealed the various connections between modern pop music and motion pictures. If you’re interested, I have a separate post on modern pop music history.

This document, adapted from my course notes, presents a journey through the evolution of film music, from the silent era’s live accompaniments to today’s hybrid orchestral scores. We’ll explore how composers like Max Steiner, Bernard Herrmann, and Hans Zimmer shaped the language of cinema, and discover how music doesn’t just accompany films, but fundamentally transforms how we experience stories on screen.

Though often referred to as “soundtracks,” this exploration focuses primarily on “scores”—instrumental music crafted specifically for films. It’s worth noting that a great score isn’t always great music in isolation; its true power lies in how it enhances a scene, not in standing alone as a masterpiece to win a Grammy. Interestingly, modern music and film emerged around the same time, and they complement each other ever since. To set the stage, we’ll begin with a broad preview of key concepts and examples, revisiting each in greater depth later.

Assorted Ideas

Our First Scene: Apollo 13 (1995)

James Horner, a brilliant composer we’ll encounter frequently, tragically died a few years ago when he crashed his personal jet into a mountain. Apollo 13 focuses on the third lunar mission. Since it was the third attempt, the public had largely lost interest in moon landings, making it an interesting choice for Hollywood drama. The film follows three astronauts who used mathematical ingenuity to survive when everything went wrong.

Scene 1: Wife Showering

An astronaut’s wife grapples with anxiety about her husband’s upcoming moon trip. She’s convinced that Apollo “13” is cursed, and when her wedding ring slips off and goes missing, she takes it as an ominous sign that she might lose her husband.

Scene 2: Astronauts Getting Ready

Cut to the three astronauts suiting up while technicians meticulously check every piece of equipment. The tension builds as we transition to the launch site, where history is about to unfold.

Cues, Not Songs

The music here is called a cue, not a song. Let’s reserve “song” for when someone’s actually singing. A cue is music crafted specifically for a film scene, designed to synchronize perfectly with what’s happening on screen.

Effects of Music

We watched these Apollo 13 scenes twice: first in silence, then with sound. Since there’s minimal dialogue, the music’s impact became crystal clear:

- Scene Transitions: Without music, jumping from one scene to another feels jarring. The music creeps in at the end of the first scene, gradually building volume and creating anticipation that makes the transition smooth. This can happen three ways:

- Music starts before the transition, building expectations so the shift feels natural

- Music hits right at the transition; perfect for shocking the audience or delivering jump scares

- Music enters after the transition, often following something dramatic like a death, giving audiences a moment to process before the emotional guidance resumes

Intimacy in Silence: The shower scene is mostly music-free, and for good reason. Add music here and it becomes overly dramatic. Without it, you focus on the wife’s actual emotions rather than what the composer wants you to feel. This silence also creates breathing room before eight minutes of intense musical drama. Where music isn’t can be just as important as where it is. Think horror movies: the real terror isn’t during the musical buildup, it’s when everything goes dead quiet right before the scare.

Emotional Ambiguity: Without music, you can’t tell what the astronauts are feeling. Nervous? Excited? The visuals alone leave you guessing.

Instrumentation and Symbolism: The astronaut preparation music features brass and synthesizer bass. Brass evokes military strength; historically chosen because it doesn’t shatter like violins during combat. Most early astronauts were military, so it also signals heroism and sacrifice. The synthesizer bass provides a steady beat that represents technology and precision: when you’re heading to the moon, you want reliable consistency.

Musical Style: The score uses a chorale style (赞美诗): church hymns from the 1600s-1700s. It follows a pattern of rhythmic notes, pause, repeat, designed so regular people could sing along without running out of breath. The astronauts even extend their arms like a crucifix at one point, reinforcing the faith and sacrifice theme. This particular style is classified as “Protestant Hymn.”

Tempo: Slow and steady reinforces professionalism. A constantly changing tempo would feel too emotional for a mission requiring mathematical precision. The controlled pace signals that this is serious business.

- Texture Evolution: As Scene 2 wraps up, strings and woodwinds take over the same melody. This smooths the transition while adding hope and grandeur, building anticipation for the rocket launch.

The Four Functions of Film Music

Why include music in films?

Picture this image with happy music: instant wholesome family vibes. Now imagine it with ominous music: suddenly it’s a completely different story. Music hijacks your emotions faster than you can think.

Movies exist to tell stories and make you believe in them, even temporarily. They want you to achieve “suspension of disbelief”: that state where you forget you’re watching actors pretend in front of cameras. Even Harry Potter needs you to buy into the wizarding world, which is why anachronisms break the spell instantly.

But here’s the paradox: music completely violates this suspension of disbelief. Real life doesn’t come with a soundtrack. So why does every movie have one? Because music is simply too powerful to ignore.

Film music operates somewhere between “emotion” and “action”: it either makes you feel something or enhances what’s happening on screen. More specifically, it serves four main purposes, often simultaneously:

Creating Atmosphere of Time and Place: Music instantly transports you. Hear Chuck Berry, and you’re in the 1950s. Pentatonic scales evoke China (or at least Hollywood’s version of it). When characters get in a car and the music gets muffled, you know they’re hearing the radio. But this relies on audience assumptions, often centered on American perspectives, which can lead to stereotypical musical choices, especially in films before the 1950s.

Underlining or Creating Emotional/Psychological Depth: Music can support what’s obviously happening or reveal hidden subtext. Picture a cheerful party where two people smile and chat, but the music turns dark: suddenly you know these two have unresolved conflict, even if they’re acting friendly.

Providing Continuity: As Apollo 13 showed us, without music, scene cuts feel abrupt. Movies need frequent cuts to compress time, and music acts as the glue, especially in montages (蒙太奇手法): those rapid sequences that compress hours into minutes. Picture a shopping montage: friend says no, friend says no, friend nods, cut to them carrying shopping bags. Without music, it’s just confusing jump cuts.

Supporting Theatrical Buildup and Finality: Music controls the emotional pacing of films. It builds tension, releases it, and provides that satisfying sense of closure when everything wraps up.

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Composer: John Williams, a master of the craft.

F3: Continuity

The film rockets from the Himalayas to Egypt in rapid succession. Music becomes the thread that keeps this geographic transition smooth.

F1: Where and When

The score flows from the iconic Indiana Jones theme (major scale, appropriately heroic) to a love theme (also major, but with strings for romantic warmth) to “Egyptian” music (harmonic minor starting on the 5th degree: the “snake charmer” sound familiar to American audiences, though culturally stereotypical). The love theme hints at romance before it actually develops, demonstrating how film composers use musical foreshadowing.

F4: Pacing

After an intense action sequence, the film needs to slow down for dialogue and plot development. The music mirrors this shift, cooling down from high energy to conversational.

Alien Resurrection (1997)

Composer: John Frizzell. The fourth Alien movie: the first two were acclaimed, the third faltered, and this one puzzles audiences but features an excellent score. It follows a woman resurrected because she carried alien queen DNA, which pirates want to weaponize.

Scene Breakdown: The resurrected woman (now part alien) plays basketball when pirates attempt to flirt with her. She ignores them until she’s had enough, then thoroughly defeats them. The pirate boss appears, she walks away, and casually sinks a backwards shot.

F4: Pacing

- Dead silence during the harassment: no music means you feel the full discomfort without emotional buffer.

- When she starts fighting, dark musical “clouds” roll in, but without much rhythm since everyone’s too shocked to process what’s happening.

- She catches the ball one-handed, and the music begins its rhythmic buildup.

- After she defeats the second pirate, the music cuts out to punctuate the end of the fight.

- It builds again when the boss arrives and questions start flying, then stops before her impossible shot so you hear nothing but the swish.

F2: Revealing Hidden Information

Call is a spy among the pirates, sent to kill Ripley (the resurrected woman), but she only knows the name, not the face. When the boss reveals she’s Ripley, Call’s reaction gets a heavy musical emphasis, foreshadowing her secret mission though the audience doesn’t know she’s a spy yet.

Watch the scene here

This above was our “greatest hits” album. Now let’s get more systematic with proper definitions and frameworks.

Diegesis

The diegesis (叙事) is the world described by the narrative. This encompasses all characters, events, and elements depicted by the film, whether explicitly shown or implicitly understood.

For example, Star Wars explicitly shows us starships, but we assume bathrooms exist on Earth within that universe even though they’re never depicted. Both are part of the diegesis.

Diegetic Music / Source Music

Music whose source exists within the diegesis. The characters in the film can hear it just as the audience can. Picture a character putting on headphones while a muffled pop song plays: that’s diegetic music.

This is also called “source music,” “direct music,” or “foreground music.”

Functions:

- Establish time and place (F1): A character listening to Elvis immediately signals the 1960s

- Create realism and immediacy: Makes the world feel lived-in and authentic

- Offer ironic commentary: Characters fighting while a child’s music box accidentally starts playing creates ironic contrast, suggesting their behavior is childish

Nondiegetic Music / Score

Music heard only by the film audience, invisible to the characters themselves. Also called “score,” “underscore,” or “background music.” This is where we’ll spend most of our time.

Original Score: Music composed specifically for the film. Individual pieces are called cues rather than songs.

Pre-existing Music: Selected music that wasn’t originally written for the film but works perfectly for specific scenes. Many films combine both approaches: mostly original score with strategic use of pre-existing pieces.

Example: Pre-existing Music As Score, Platoon (1986)

Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” (1938), a classical piece, has appeared in numerous films including The Elephant Man (1980) and Sicko (2007). In Platoon, composer George Deleure created original scores but also incorporated Barber’s piece. Instead of intense war music, this classical selection underscores the profound sadness of loss. Watch the scene

Score vs. Soundtrack

Generally, scores are original compositions while soundtracks feature pre-existing pop songs. The distinction isn’t precise: everything else blurs together. Soundtrack songs might be decades old, say from the 1940s. A music supervisor, not a composer, selects which pop music fits each scene.

Adapted Score

Pre-existing music reworked to fit the film. Since this music wasn’t originally designed for cinema, it needs adjustment for timing, pacing, and dramatic effect. The original artist or another composer can handle the adaptation.

Example: The Sting (1973), Adapted Score

Originally composed by Scott Joplin as a ragtime classic, the music works beautifully after adaptation, though it’s historically curious: the film is set in the 1930s while ragtime peaked around 1900-1910.

Compiled Score

Pre-existing music used without adaptation, straight out of the box.

Example: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Compiled Score

Kubrick used classical pieces as-is, creating one of cinema’s most memorable musical experiences without a single note of original composition.

Describing the Music

What style characterizes the music? What instruments are used (including voice as an instrument)? How do these choices relate to the film’s needs?

Example: Restoration (1995)

Set in the 1600s, the film uses period-appropriate music, both adapted and unaltered, mostly as diegetic music. We’ll focus on Henry Purcell’s work from the late 1600s.

Purcell’s music exemplifies the baroque era (巴洛克风格), characterized by constant dynamics and tempo throughout. This reflects the 1600s emphasis on control and elegance. However, this consistency makes it problematic as film score because cinema needs F4: pacing variation and dynamic change.

James Newton Howard adapted Purcell’s music, using the same repeated melody as a character climbs stairs, but with cinematic modifications. Watch the adaptation

Example: Local Hero (1983)

The story follows an oil company employee sent to Scotland to convince a village to sell their land for an oil plant.

F1: Mark Knopfler composed an original score in Anglo-Celtic folk style. Anglo-Celtic refers to the British Isles (England, Scotland, Ireland), and the music employs traditional Scottish elements like bagpipe melodies (风笛). This creates authentic geographical atmosphere.

This plays during the film’s peaceful resolution, a happy ending that contrasts dramatically with Restoration’s intensity.

Example: The Godfather (1972)

The story centers on an aging Sicilian gang leader, the “Godfather”, facing disrespectful young criminals from other gang families and an assassination attempt. He must choose a successor from among his sons, but his most capable son wants nothing to do with the family business.

The Godfather Theme:

- Brass (trumpet) solo with echo: The solo represents the godfather’s isolation; all responsibility rests on his shoulders. The echo suggests a single voice in a vast, empty space, emphasizing loneliness.

- Transition to trumpet with woodwinds playing waltz: The happier waltz reflects the opening scene: the godfather’s daughter’s wedding. Brass appears in traditional Sicilian wedding music, while the waltz style evokes old-fashioned traditions, mirroring the traditional gang leader himself.

Emotional vs. Action Music

Film music generally falls between two approaches:

1. Playing the Drama

Music reinforces or foreshadows emotional elements within the narrative. Even if a scene appears normal, the music might be ominous, revealing hidden tension. This approach ignores momentary visual changes, camera angles, or quick cuts, focusing instead on deeper emotional currents.

2. Hitting the Action

Music directly underscores visual events. Car chase scenes get fierce, intense music that matches the on-screen action. This doesn’t include music that smooths editing cuts; that’s about continuity, not action.

Most film music combines both functions strategically.

Example: How to Train Your Dragon (2010)

Scene: Hiccup takes his first ride with Toothless, using a cheat sheet to control the dragon.

- (00:39) Theme begins by playing the drama, capturing Hiccup’s excitement

- (00:51) Music “swells” (激昂) during the overhead shot

- (00:58) Hits the action when Toothless crashes into a rock (notably, this doesn’t repeat for subsequent crashes; that would become silly)

- (01:20) HTA as the cheat sheet comes loose and Hiccup falls, the theme turning nightmarish

- (01:53) HTA as Hiccup regains control, returning to the main theme

- (02:01) Playing the drama: the main theme returns when Hiccup throws away the cheat sheet, trusting his instincts, symbolizing complete trust between boy and dragon

Musical Characteristics

1. Melody / Theme

Melody and theme are interchangeable here. Considered the most “recognizable” musical element, it’s common to assign specific characters, objects, or situations their own themes.

This isn’t new: opera has long assigned themes to characters. However, traditional opera simply repeated the same music whenever a character appeared, regardless of dramatic context.

German opera composer Richard Wagner revolutionized this with “Thematic Transformation”: themes should constantly vary in response to narrative development. Happy Birthday in major when joyful, Happy Birthday in minor and slower when the story turns gloomy. Wagner called this the “leitmotif“—we use this interchangeably with melody and theme.

Example: Star Wars (1977), Thematic Transformation

John Williams demonstrates Luke Skywalker’s theme undergoing transformation across four scenes:

- Film opening: Grand, iconic version establishing Luke’s heroic destiny

- Luke’s introduction on the farm: Gentle version with French Horn, reflecting his humble origins

- Death Star escape scene: Playful, energetic version suggesting safety and adventure

- Climactic torpedo shot: Serious, dangerous version emphasizing the high stakes

2. Tempo / Pulse

Musical speed influences narrative tempo. Romantic scenes typically use slower tempos; battle scenes demand faster ones. Sound design also affects time perception: the sharp sound of a sword being drawn makes the action feel quicker.

Example: The Return of the King (2004)

This Lord of the Rings installment features extensive battle scenes that should feel intense and fast-paced. However, the music for this apocalyptic battle is unexpectedly slow, creating sorrowful rather than triumphant feelings.

This scene also blurs the line between source music and score: The king orders a hobbit to sing during dinner (source music), but as the scene shifts to the battleground, the singing continues with added echo (becoming score). As battle progresses, orchestra joins not to enhance the singing, but to create dark, chaotic atmosphere. The music cuts precisely after the enemy’s arrow volley, returning to the king finishing his meal.

3. Harmony

The combination of notes creates different emotional atmospheres:

- Consonant or dissonant?

- Orderly or chaotic?

- Tonal or atonal?

Major scales are always consonant, orderly, and tonal. These harmonic choices fundamentally shape how we perceive the diegesis.

Example: The Cider House Rules (Highly Consonant)

Major scale, highly consonant harmony creates lovely, safe, calm feelings.

Major scale, highly consonant harmony creates lovely, safe, calm feelings.

Example: Meet Joe Black (Between Consonant and Dissonant)

The story follows Death asking a dying man why humans fear death, then falling in love with the man’s daughter. Some sections feel resolved and consonant while others feel dangerous and dissonant, reflecting the music’s movement between major and minor territories.

The story follows Death asking a dying man why humans fear death, then falling in love with the man’s daughter. Some sections feel resolved and consonant while others feel dangerous and dissonant, reflecting the music’s movement between major and minor territories.

Example: Aliens (Dissonant)

Ripley battles aliens while trying to save a girl and reach their ship. The predominantly dissonant harmony creates uncertainty about the characters’ survival, with one brief consonant moment when the girl safely boards the ship.

Ripley battles aliens while trying to save a girl and reach their ship. The predominantly dissonant harmony creates uncertainty about the characters’ survival, with one brief consonant moment when the girl safely boards the ship.

Technical Details: How It’s Done

How are films actually produced?

Note: We don’t cover computer-animated films, which follow very different processes. Voice work happens before rendering, and the production timeline differs significantly from traditional filmmaking.

Basic Timetable of Film Production

Preproduction

Gathering everything needed: script, financing, casting, costumes, location scouting, and countless other preparations.

Production

Also called “principal photography.” This involves finalizing the script and production design, then actually shooting the film.

Director vs. Producer: The producer handles business aspects (raising money, logistics, transportation), while the director focuses on the film’s creative vision and appearance.

Postproduction

After “wrap” (completion of shooting), extensive work remains. Films aren’t shot in final order; all editing happens in postproduction. Scenes at the same location are filmed together for efficiency. The same scene gets multiple takes from different camera angles: 1-shots (single character), 2-shots (two characters), etc. Editors piece these together for optimal presentation, along with visual effects.

Audio gets added here too. When actors shout in a “loud bar,” they’re actually performing in silence; bar noise gets added in postproduction.

Music is typically added after scenes are assembled, so composers work with nearly finished footage. This creates a hard deadline tied to the release date. Music becomes one of the final elements, with composers averaging 5-8 weeks to complete their work.

How Composers Make Scores

Composer involvement varies based on working style and project specifics.

Scripts

Composers can get a head start by reading scripts before shooting finishes. If set in 1980s Japan, they can research Japanese musical styles immediately. Scripts also reveal whether music should be original or pre-existing, diegetic or score.

However, scripts have limitations: they can change significantly, and they lack timing and pacing information crucial for musical composition.

Screenings

Composers see the film at various stages:

- Rushes: Daily footage from each shooting session. Limited value beyond getting a sense of the film.

- Assembly cut: All scenes the director might use, including multiple takes. Can run extremely long (9 hours for Titanic). Composers get ideas but can’t work seriously yet.

- Rough cut: Closer to the final version, better for beginning composition work.

- Fine cut/Locked cut: Nearly all editing completed, with finalized pacing and timing. Most composers begin serious work at this stage.

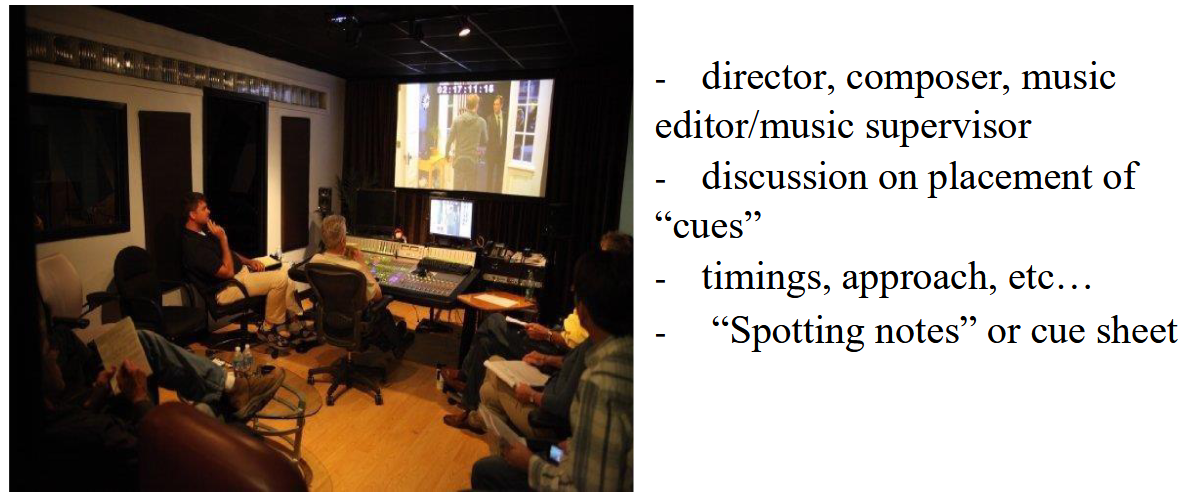

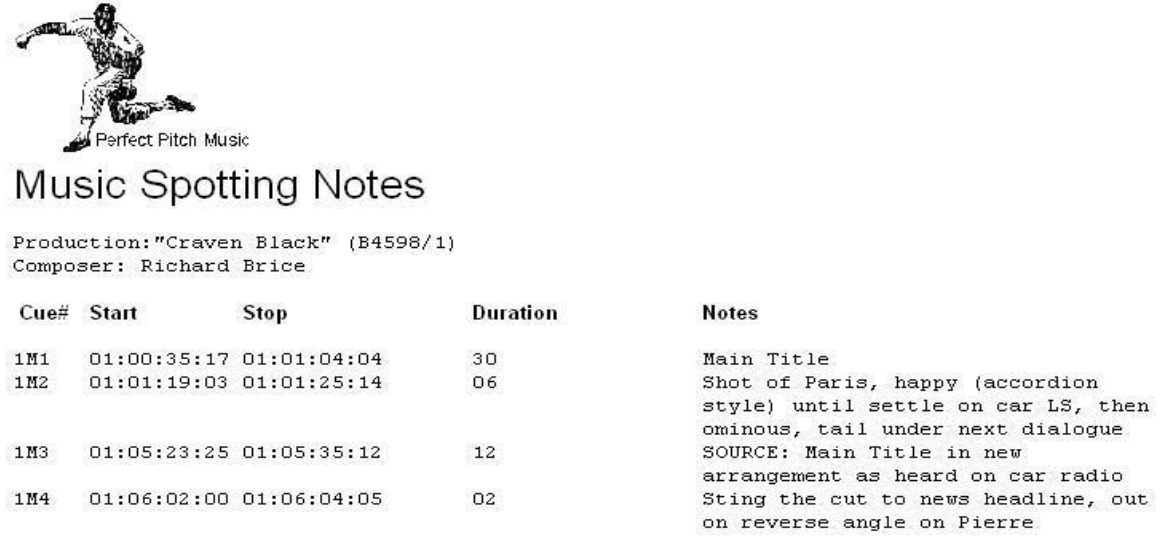

Spotting Session and Cue Sheets

After editing completion, the director, composer, and music editor review the film together, discussing music placement, timing, emotional approaches, and musical style. The music editor compiles these discussions into “spotting notes” or a “cue sheet.”

Temp Music

“Temp” (temporary) tracks present a controversial challenge. During early production, directors often want to hear scenes with music, so music editors add “temporary placeholder music” from existing films or classical pieces.

Pros: Helps directors (who may struggle to articulate musical desires) communicate their vision through reference tracks.

Cons:

- Composers hearing temp tracks first may find it hard to generate original ideas

- Directors become attached to temp music after repeated viewings, wanting to keep as much as possible without copyright issues

The tension: “Directors want to keep as much temp music as possible without legal problems; composers want to keep as little as possible without being fired.”

Composing

Usually 5-8 weeks until delivery of the finished score. The fixed release date creates short, hard deadlines. If production runs overtime, music time shrinks further.

Who’s involved?

Composers: Create musical sketches (sometimes pencil and paper) containing core musical ideas

Orchestrators: Formalize sketches, distributing melodies among instruments. Skilled in composition, music theory, and orchestral knowledge.

Synth Demonstrations: Instead of piano demos, composers now use synthesized instruments to preview music for directors before expensive recording sessions.

Copyists: Produce final sheet music for each instrument, adding performance details like bow marks for strings and breath marks for woodwinds.

Music librarians: Organize sheet music distribution, ensuring every musician receives correct parts for each scene. With expensive musicians and studio time, logistical errors are costly.

Conductors and studio musicians: Studio musicians must be excellent sight-readers. Some composers conduct their own music.

Recording sessions feature musicians and conductor performing while scenes play on a projector, often with moving markers to ensure synchronization.

Mixing

After recording, the director works with mixing engineers to balance dialogue, music, and sound effects in the final soundtrack.

Western Classical Music History

Understanding classical music history helps explain how film music developed in North America.

Baroque Period (1600-1750)

Key Composers: Vivaldi, Handel, Bach

Development of “Common Practice” that musicians still use today, including the major/minor system. Music structure held highest priority—strict rules mattered more than emotions. While pleasant, the music remained very rigid.

Consistent tempos and textures throughout, with terraced (阶梯式的) dynamics that change suddenly between preset levels.

Example: J.S. Bach, “Brandenburg Concerto No. 6” 3rd Movement (1721)

This style proves unsuitable for film because it cannot react to emotions. If a scene turns intense but the music is in a soft section, it can’t adapt.

Classical Period (1730-1820)

Key Composers: Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven

Baroque’s polyphonic complexity gave way to melody plus chords. Melody and emotion became more important, though structure remained paramount. Expanding variety of tempo, texture, and dynamics allowed more emotional responsiveness.

Example: W.A. Mozart, “Symphony No. 40” 1st Movement (1788)

Romantic Period (1800-1910)

Key Composers: Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Strauss

Expression of emotion became supreme—more important than structure. Even greater range of tempo, texture, and dynamics served emotion and narrative.

Example: R. Wagner, “The Magic Fire Music” from Die Walküre (1870)

“This sounds very much like film music.” Actually, it’s the reverse: film music sounds like Wagner. Wagner’s music dominated the 1860s-1880s. When motion pictures emerged in 1895, early film composers learned from Wagner’s innovations.

Progression of Movies

THE SILENT ERA (1895-1927)

Melodramas: Films had theatrical precursors. While most plays used little music, melodramas—popular working-class entertainment in the 1800s—featured extensive musical accompaniment. These were essentially “soap dramas” on stage.

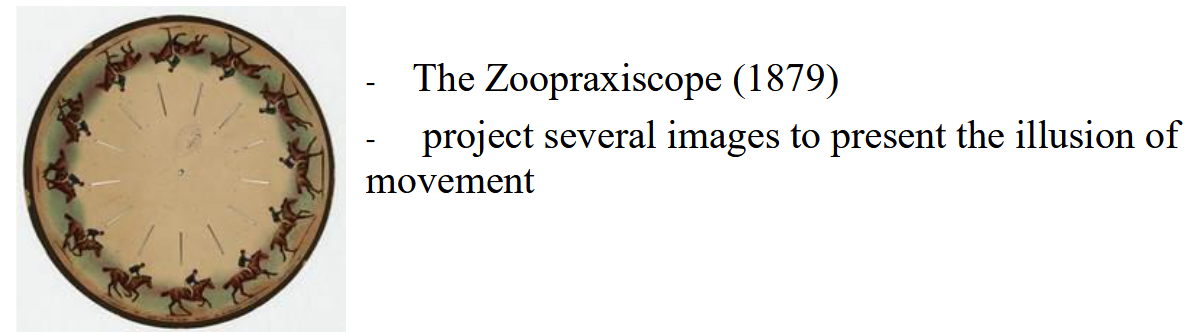

The Persistence of Vision: Scientists discovered that images played at approximately 11-12 pictures per second create the illusion of motion rather than static images.

Thomas Edison’s work

Edison’s Kinetoscope could record and play images fast enough to create motion illusion. He also developed audio recording, later combining them. However, viewers had to peek through a small hole to see images, and audio and video were intentionally unsynchronized.

First Projected Films

The Lumière Brothers, Paris, December 28th, 1895, are documented as the inventors of motion pictures. While Edison had working video devices, the Lumières were first to project video onto screens so multiple people could watch together.

Their first motion pictures showed everyday scenes: street views, picnics, trains demonstrating the technology. The train was famous because audiences thought it might burst through the wall. Notice that there was music with the video from the very beginning.

Why did the Lumière Brothers include music from the start?

Pragmatic: Mechanical noise and problems. Music entertained audiences during technical difficulties and covered projector noise.

Psychoanalytic: Audiences were disturbed by ghost-like images. First-time viewers found black-and-white, soundless moving people creepy. Music made them seem more alive, less supernatural.

Continuity of Tradition: Long history of musical accompaniment for visual presentations. Music naturally accompanied visual entertainment.

During the Silent Era

What did movies do with music during the long gap before synchronized sound?

- Adaptations/compilations of classical music

- Adaptations/compilations of pop songs (which were also emerging)

- Originally composed scores or improvised scores by talented musicians

Venues: Vaudeville Theatres

Live variety shows featuring comedians, skits, dancers—all with musical accompaniment. Found everywhere, they began including films in 1896, initially as brief intermissions that grew increasingly popular. By the 1920s, film-specific venues had largely replaced Vaudeville theatres.

Nickelodeons

, small ensembles (about 3 musicians in better establishments), or gramophones playing records.

Georges Méliès stands among the first true film directors. While not creating the first narrative motion picture, he produced some of the more “mature” examples: 10-minute films with multiple scenes, proper sets and costumes (not just whatever people happened to be wearing), and experimental camera effects. He pioneered techniques like starting the camera, having a person get “bombed,” stopping the camera, letting the person walk away, then restarting the camera to create the illusion of disappearance.

“A Trip to the Moon (1902)” featured original scoring and hand-colored prints created frame-by-frame by women workers. These colored versions were nearly impossible to copy, making them extremely rare. Watch the film

However, musical practices remained haphazard. Musicians played whatever they felt like, with no intentional effort to match scenes. Music varied drastically from venue to venue: some places had skilled musicians, others had different repertoires, and some had no music at all.

1905-1910

Narrative films gained popularity while growing longer and more complex. Directors began recognizing music’s importance. Though musical choices still varied by venue, it became clear that musicians who tried to synchronize with the movie created superior experiences.

Music’s purpose shifted from mere audience entertainment to “playing the picture”: supporting the drama and helping audiences follow the plot. Music should be “fitting” or “synchronizing.” However, this wasn’t universal; many musicians continued playing whatever they preferred, following decade-old habits.

1910-1920

, providing rich instrumentation for movie scenes. Organ pipes also created sound effects: starter pistols simulated gunshots, coconuts mimicked footsteps.

How Did Music Develop?

Early attempts at original scores existed, but standard practice involved compilation of classical or popular music, or improvisation. The major problem: the same movie featured different music at different venues.

Efforts emerged to standardize movie music:

1909: Edison Film Company

Thomas Edison began providing “musical suggestions”: scene-by-scene recommendations for appropriate music. These lacked strict timing, organizing only by scenes.

1912: Max Winkler (Carl Fischer Music)

by J.S. Zamenik included categories like “Hurry Music” and “Fighting Music.”

Musicians generally didn’t want to purchase these books, so this approach also failed.

Trade Papers About Film Music

: magazines functioning like modern blog posts. They debated rules film music should follow. Some debates were questionable but interesting:

Music should be continuous because in silent films, music provided the entire audio experience. It should start with the film and end with the film, often requiring multiple musicians for seamless coverage.

Musicians recognized the difference between diegetic (source) and non-diegetic music, arguing musicians should always try to play source music. If an army marches with a military band in the movie, the musician should play military music regardless of their instrument (piano instead of brass).

Wagner’s “musical theme” concept worked well for films: use the same song for a character every time they appear.

Some argued movies should only feature “good music” (classical like Mozart) to “educate” audiences. This was mostly arrogance; the most important thing is music that fits the film, not “high” or “low” culture.

Despite heated trade paper discussions, most 1920s film music remained unstandardized. Musicians varied in skill across venues, cue sheets and scores went missing, and some venues had no musicians at all. The ultimate solution: technology that embeds music into films for consistent synchronization across all venues.

Transitioning To Sound

Sound and silent films coexisted for several years. People didn’t immediately consider sound films superior due to economic and cultural factors.

Economic issues: Sound films required microphones during filming, amplifiers and speakers for projection—significantly more expensive.

Cultural resistance: Silent films had existed for over 20 years. People were accustomed to them and found sound films (“talkies”) weird.

Sound film demonstrations appeared as early as 1922, with two major approaches:

1. Sound On Film

Print photographs of sound waves on film tape edges.

, wants to be a pop jazz singer instead. Kicked out of his family, he returns as a successful jazz star to perform for his mother (in a scene with sound). Played by a real-life pop and movie star.

Most of the score was compiled or adapted. Used Vitaphone System to record brief dialogue, while most of the film remained music-only. Synchronizing even short dialogue required projectionists to constantly adjust tape speed. Long silences followed dialogue as projectionists switched from dialogue to music disks.

Most theaters still lacked Vitaphone, so the film had to remain mostly silent for compatibility. “Hey, if you watch this in a big New York theater, you can hear them talk!”

This became a major financial and cultural success, signaling the “beginning of the end” of the silent era. Hollywood realized sound films would dominate.

Change To Sound On Film

Sound on Disk had early advantages, but Sound on Film became standard by the late 1920s and early 1930s. Synchronization proved king—as technology improved, audio quality became adequate. However, the prolonged battle between systems made most theaters hesitant to invest in either, delaying sound system adoption until the early 1930s.

Sound film dominance changed many aspects of filmmaking:

1. Aesthetics

Film had developed as a silent visual medium. Silent film actors had to adjust their acting styles and voices. Without dialogue, emotions required exaggeration; with sound, continued exaggeration looked weird. Many silent stars had poor voices, accents, or didn’t speak English.

Many directors worried about using non-diegetic music: “Where does the music come from?” Previously, audiences knew music came from live musicians, avoiding confusion. With sound now including dialogue, music created confusion: “I can hear this music—can the characters hear it too?” Though non-diegetic music was everywhere in silent films, it largely disappeared from 1928-1932.

2. Making Films

. Expensive “sound stages” (soundproofed buildings) were built to reduce outside noise.

Script writing was just invented—no dialogue before meant no scripts needed until now!

3. Showing Films

A movie about making sound films in 1927 and the challenges faced. Issues with filming: speaking into microphones, actors not following scripts. Issues with projection: sound-picture synchronization, sound mixing.

Max Steiner (1888-1971)

- Walking back onto the stage: Club dancing music returned

This music enhanced the movie’s effectiveness. David Selznick, a leader at RKO studio, recognized Steiner’s excellent work.

Symphony of 6 Million / Bird of Paradise (1932)

—a key part of his style. In scenes where Gypo walks to a “wanted” poster of his friend offering $20 reward, music Mickey Mouses to match his steps’ rhythm, pulling down the poster, etc. Gypo’s actor was bad with rhythm, so music had to accommodate his steps.

Steiner used musical quotes, rearranging Rule Britannia to sound loud, overpowering and oppressive (with brass) as Gypo takes down his friend’s wanted poster. Through thematic transformation, Steiner portrayed Britain as villains.

Katie’s theme is jazz-influenced. Jazz can feel smart and urban, but here creates dark urban atmosphere reflecting Katie’s profession as a prostitute. It suggests she’s smarter than Gypo. Katie dresses like the Virgin Mary stereotype (pure, innocent), then transforms appearance when removing her head covering, revealing her true nature.

Excellent action-hitting occurs as she solicits customers, a client smokes, Gypo discovers this and throws out the client, she looks at the $20 poster for two tickets to America, and Gypo questions what she’s thinking about regarding the $20.

Steiner quotes a thematically transformed version of Yankee Doodle.

This movie won the Academy Award for “Best Original Score”—one of the first because original scores were just beginning to appear. Much more advanced musically compared to King Kong.

More On Max Steiner

, Casablanca (1942), and A Summer Place (1959). Steiner disliked pop songs, so he composed scores that sounded like pop songs. He created the main theme for A Summer Place, which was later rearranged into a successful pop song.

He started at RKO, moved to head of music at Warner Bros from 1937-1953, with most important works in the 1930s-50s. Credited for over 300 films throughout his career.

1930s: Defining Sound Film Conventions

Sound films began as extensions of silent films, but by the end of the 1930s, they became their own medium through technical and aesthetic changes. King Kong, despite having sound and music, still carried much silent era characteristics due to immaturity. By the late 1930s, films had developed significantly and resembled modern cinema.

Studio System

The 1930s began with many small studios, but as the industry evolved, larger ones acquired smaller ones, leaving 5 major and 3 minor big studios. The Studio System meant everyone involved in moviemaking became employees of big studios, paid weekly salaries.

This was problematic for actors: if someone signed a 5-movie contract at $100/week, then became a star after the first movie, they still had to complete the remaining 4 at the same low rate.

However, for productive filmmaking, this was beneficial because you knew exactly what a movie would cost—just add up the salaries. Thus, the 1930s became Hollywood’s most productive period. This was the height of the “Studio System.”

The “Émigré” Composer

Nazis forced out many great European artists and intellectuals (especially Jewish). Many became famous film composers. Alfred Newman and Herbert Stothart were among the few important American-born composers in this period.

- Alfred Newman: Thomas Newman’s father, composed the famous 20th Century Fox intro theme

- Herbert Stothart: composed the score for The Wizard of Oz

The next composer we’ll discuss extensively is an émigré.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

.

His father had connections with major musical figures who frequented their house since Erich was young. His piano teachers included Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

He became a famous conductor, known for interpreting Felix Mendelssohn’s music for Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (which includes the Wedding March). A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the only Shakespeare play originally designed with music.

Hollywood wanted to film A Midsummer Night’s Dream and needed someone for the music. Since Mendelssohn had long passed away, they hired Erich, known for conducting Mendelssohn’s music, in 1934.

Erich enjoyed his Hollywood experience, impressed like Steiner by the quality of musicians and facilities. However, he didn’t want studio contract constraints. He was the only major 1930s composer not on a studio contract. He worked in operas and returned to Hollywood annually when called for film music.

He won the Academy Award for Anthony Adverse (1936). In 1938, asked to score Robin Hood, he initially declined, feeling his romantic style didn’t fit action films; he actually recommended Max Steiner. But executives persisted.

However, he received a telegram upon returning to his hotel saying Austria was occupied by Nazis, forcing him to stay permanently in the U.S. He took the job to make a living, and his family managed to escape to America.

He won the Academy Award for Robin Hood, marking the first time the award went directly to the composer rather than the head of the music department (music director). Previously, composers didn’t receive awards—their music directors did.

After WWII, Korngold wanted to return to concert writing, but his style was considered old-fashioned, losing his standing as a “serious composer.” He felt depressed because he was no longer recognized for operas and concerts. His father also thought film music work was childish.

He wrote only 19 film scores in 12 years (much slower than Steiner) as a freelancer.

Korngold’s Style

Since Korngold studied in Vienna in the early 1900s, his style resembled 19th century romanticism (like Wagner). As one of the early film musicians “writing the rulebook” for film music, he considered his film scores to be like “little operas“—treating them as instrumental bits of opera without singing. He focused on “extended melodies” through thematic transformation.

Korngold pioneered music for battle scenes, which became the standard:

- Loud dynamics: battles feature many sounds (swords, horses, etc.)

- Rapid scale passages: rapid playing generates excitement, and scales are easier than complex melodies for musicians sight-reading under time pressure (expensive studio time)

- Irregular, aggressive accents: accents between beats rather than on downbeats create unstable feelings, making audiences nervous

- Occasional motive reference: interjecting villain themes when bad guys are winning, or hero themes when good guys triumph

The Sea Hawk (1940)

, while Britain employed smaller, agile ships operating like pirates to damage Spanish vessels—these were the “sea hawks.”

Opening Credits

Korngold wrote an overture during opening credits, including snippets of main themes to come. Used an ABA structure: hero theme / love theme / hero theme.

Heroic theme uses brass fanfare (喇叭或号角嘹亮的吹奏声): constant, rigid tempo with precise notes, used for grand, solemn occasions like royal events and associated with military.

Love theme uses strings: the orchestral section most effective at appealing to emotions, employing rubato (自由速度) where the orchestra slows at certain parts but speeds up later, contrasting the heroic theme’s rigid tempo.

The Battle

Applied the four battle music techniques discussed earlier. Used framing the narrative (phrasing the drama) to parallel the battle.

Music can shift between “playing the drama” and “hitting the action” if scenes change slowly enough. When changes occur too rapidly, music can’t capture everything; composers create music to “set the overall mood,” only hitting action or playing drama for particular moments. This mood-setting music is “framing the narrative.”

Harp (竖琴) featured prominently for easy rapid note playing. Music dropped during dialogue for clarity. Sustained notes built anticipation when English forces nearly surrendered, also providing pacing after intense action. The score shifted from framing narrative to hitting action more closely, allowing natural conclusion when music stops.

At battle’s end, a natural horn plays source music to signal surrender, blending source and score. Natural horns can only play certain major notes, but when this “natural horn” plays notes only possible on trumpet, it signals transition from source to score as orchestra enters—an opera technique.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

rule England unfairly over Saxons. Evil Prince John, a Norman, treats Saxons poorly, prompting Robin, also noble, to rob the rich and help the poor.

Opening Credits

Overture: ABC structure - 3 Themes

First two themes based on marches. Since marches are group activities, these aren’t “Robin Hood’s theme” but represent Robin Hood’s gang (“merry men”). Placing these first emphasizes the movie’s core message: “more people stronger.”

Final theme sounds like the love theme: rubato, strings.

Transition into diegesis: Opening credits aren’t immersive since they remind viewers this isn’t real. The end must transition smoothly into story for “suspension of disbelief.” Korngold achieved this by building to a fanfare at credits’ end, syncing drums with the drum player’s actions in film.

Robin’s Theme

Robin has his own theme: not in opening credits, fanfare style (since he’s a hero), short.

Meets Little John

Introduces a recurring theme playing when each main character joins the merry men. Little John’s version, first played, uses French horn (tough instrument, suggesting he’s a skilled hunter or woodsman).

The happy theme plays through their playful fight, implying no one gets hurt. Music blends with source music for comedy. Hits the action during short staff duel (also comedic). Mickey Mousing occurs when sidekick plays lute. Woodwind “water” theme plays when Robin falls—a common opera technique. Concludes with merry men theme.

Meets Friar Tuck

Similar to Little John scene. Initial theme played with bassoon (too high for bassoon) and muted trumpet for comedy effect.  represents Robin’s patriotic love for King Richard, played when discussing saving the country. Most dramatic when King Richard reveals himself: quiet cello.

Summary: Korngold’s Style

Wrote in 19th century Wagner romantic style from his symphonic and opera instrumental background. Focused on thematic transformations, often framing narrative. Limited Mickey Mousing, using it only for comedy—contrasting with Steiner who Mickey Moused everything, even serious scenes.

1930s: The Great Depression

, Robin Hood (1938), Wizard of Oz (1939).

Into the 1940s

The 1940s: Stories became more realistic, often set in the real world with psychological drama bringing character-driven narratives. Unlike Robin Hood’s absolute good versus Prince John’s absolute evil, 1940s characters existed somewhere between extremes, revealing the “dark side” of human condition.

Film Noir

Influenced by German Expressionism (表现主义). German films were quite mature before WWII. During the 1930s, many German directors fleeing Nazis ended up in Hollywood.

Expressionism presented humanity’s dark side through nightmarish images, making extensive use of shadows and lights. Example: Nosferatu (1922).

German film 1930s example:  they were compared to pre-war films like Wizard of Oz. They called them “black films”—Film Noir.

Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995)

. Did film work in England, 1934-1939. Due to WWII making England inconvenient for filmmaking, he moved to Hollywood while completing “The Thief of Bagdad (1940).”

was in color? Similar to sound film debates when technology first became possible, color films didn’t immediately dominate. Many films remained black and white for considerable time. Also, color films were expensive.

Big studios had difficulties accepting “modernism”:

[!quote] Quotation from Palmer, Christopher: Miklós Rózsa. A Sketch Of His Life And Work. (1975) “When it was pointed out by the head of Paramount’s music department that the score for “Double Indemnity” (1944) was anything but “attractive”, Rózsa shot back that the film was about ugly people doing vicious things to each other and the music reflected precisely that. Paramount’s music director was furious, but Rózsa enjoyed the support of the director Billy Wilder, and the music remained as Rózsa wanted.”

Spellbound (1945) and The Lost Weekend (1945)

, though this never happened. Famous Theremin player: Clara Rockmore.

The Lost Weekend Video Sample I

Author protagonist (Burnham) finishes drinking at a bar, determined to start writing, returns home. Music is consonant and energetic. Writes briefly, then sees empty liquor bottle, wants to drink again. Theremin theme starts, going from consonant to dissonant.

Music intensifies as he searches for alcohol he knows he hid while drunk. Doesn’t find alcohol, calms down, music settles with only theremin remaining.

This is visually a small scene—just a guy looking for alcohol at home. Nobody dies. However, music made the visually small scene intense and horrifying. Music is the monster here. This is common in film noir: no intense action, but dialogue and details make scenes intense.

Alcohol in 1945 was common and rarely criticized. This movie was rare in taking alcohol issues seriously.

The Lost Weekend Video Sample II

Scene where Burnham drinks at a bar but has no money, steals a lady’s purse, goes to bathroom for money, returns wanting to pay.

Only source music plays: piano player performing pop song at bar. Plays constantly during stealing. Instead of intentional score representing stealing, constant source music makes stealing more subtle, like watching a real person steal.

When he returns from washroom wanting to pay but gets caught stealing, source music instantly stops, creating shocking contrast. As he gets kicked out, source music resumes, piano singing “someone stole a purse,” mocking Burnham.

This scene and music largely change audience perception of Burnham to pathetic drunk man.

We’ll pause Rózsa here. He’s also important in the 1950s with very different pictures than film noir. Rózsa’s career divides into three major periods.

The 1940s saw increased numbers of American-born composers rising to prominence, such as Bernard Herrmann and David Raksin, after the 1930s “Émigré” period of European immigrants.

David Raksin (1912-2004)

during big band era. Worked on Broadway for 15 years.

Charlie Chaplin

but couldn’t write sheet music. Raksin was hired to help Chaplin compose musical ideas into notation.

Raksin made connections with Chaplin and director friends, entering film industry through these relationships.

Laura (1944)

. Raksin chose this because Laura is dead, so he used this theme representing her ghost, which doesn’t change since she’s dead. Music is closely associated with Laura, representing her “ideal” and her ghost, giving insight into McPherson’s mind.

After movie fame, many pop singers covered Laura’s theme with added lyrics.

Video Example: Laura 1

Focus shot on Laura’s portrait—sophisticated/urban, almost unearthly, ethereal. Laura’s theme plays during opening credits. After credits, we hear main character McPherson’s inner thoughts; Laura’s theme continues. Theme stops as McPherson speaks his first line, indicating we’re now out of his mind into real diegesis.

Hearing characters’ inner monologue is common in film noir.

Video Example: Laura 2

Lydecker’s Story Part A. Lydecker and McPherson go to restaurant. Since it’s a restaurant, music begins with source music of piano player performing Laura’s theme.

Recall Raksin made Laura’s theme after shooting (director intended “Sophisticated Lady”; Raksin created Laura’s theme last minute), so piano player played dummy music during shooting. Raksin made special arrangement of Laura’s theme fitting piano player’s finger movements.

Lydecker talks about his story with Laura; music transitions to score entering the story. Laura’s theme.

In Lydecker’s memory story, Laura approaches wanting endorsement for a pen advertisement, but Lydecker refuses while eating lunch. Laura’s theme switches to Waltz—metaphor for the struggle between Laura and Lydecker, where Laura wants endorsement and Lydecker wants to play with her patience. They’re “dancing” like a waltz.

Laura loses patience and argues back. Laura’s theme returns, demonstrating she’s no longer hiding feelings to play “waltz” with Lydecker. She’s showing true feelings.

Video Example: Laura 3

Lydecker’s Story Part B: Lydecker becomes intrigued, starts dating Laura. Talks about helping her career; she’s good because she doesn’t talk much, just listens.

Theme grows in complexity as Laura’s career grows. Notice Laura doesn’t speak—Lydecker and music speak for her. Mirrors Lydecker’s desire for Laura to just listen, not talk. Lydecker is a collector wanting to collect Laura as an object.

Montage of Lydecker discussing dates with Laura—music creates continuity. Seamless transition between source and score of Laura’s theme.

Video Example: Laura 4

Scene of McPherson in Laura’s apartment. McPherson cycles between: restless (agitated music), sees something about Laura and calms down (Laura’s theme plays briefly).

Music balances following action and reflecting McPherson’s internal state as he searches. When taking action, music is agitated. When seeing Laura’s portrait or belongings, Laura’s theme plays briefly, and he calms down. Note music’s connection to the portrait.

Laura returns to her apartment. Turns out her friend with similar body was murdered. Since it was shotgun to head in Laura’s house, everyone thought it was Laura. She was just at cottage, letting friend care for apartment.

Laura’s theme was used frequently until this point for anything about Laura. However, when Laura actually appears in flesh, Raksin left the scene with absolutely no music. The idea: Laura’s theme was about her ghost or “idealized,” “perfect” version. When Laura finally returns, she isn’t the “goodness” or “perfect young woman” discussed. Thus, this “idealized” Laura theme doesn’t play for real, flawed Laura, and never appears again for the rest of the movie.

The 1950s

End of the Studio System

Prior to the 1950s, the movie industry was dominated by 8 major studios where everyone involved in filmmaking was a studio employee. Benefits: studios knew exact movie budgets. Downside: this was monopoly—you couldn’t make movies outside the 8 major studios.

Government monopoly complaints existed long ago but were ignored during WWII while government focused on war. In the 1950s, with war over, government pressed monopoly issues. Finally, the Studio System broke down in the 1950s.

Competition With TV

TV was invented long ago but really popularized in North America in the 1950s. Why travel to movie theaters when you can watch at home?

Movies competed with TV in two main ways:

Competition: Technology

Movie theaters had color films; TVs couldn’t. This led to more colored films, though some remained black and white.

Movies used to be only 4:3 (all previous discussed movies). TVs were also 4:3. To make experiences more unique, movies started using much wider aspect ratios:

. About a Jewish prince betrayed and sent into slavery, who becomes chariot driver, then Roman army general, seeking revenge on betrayers.

Visually spectacular but essentially no narrative development during scenes. Focus is on sound and image grandeur. Music is tonal/orchestral again—somewhat back to “traditional” Wagner tonal music because atonal Modernism doesn’t fit epic films.

Competition: Subject Matter

Movie and TV content competed. Movies had been getting increasingly sexy and violent, drawing complaints from women and Christians.

March 1930: The Production Code (Hays Office) was created:

- No implied sex scenes except married couples

- Criminals must be caught

- etc.

Rules were voluntary until 1934. From 1934 briefly after, violations meant fines or no theater showings. Famous example: Gone with the Wind—”Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn” incurred language fines.

Compared to movies, TVs were even more restricted since children could potentially watch at home, and TV content was completely controlled by advertisers worrying parents.

Movies tried using more controversial content, pushing Production Code boundaries to compete with TV. Since movie theaters could restrict audiences (unlike home TVs), some places started showing adult-only films.

This was strengthened by foreign films: Italian and French films didn’t conform to production codes and featured more provocative content.

Hollywood wanted to compete with TV and foreign films, pushing for more controversial content. This period saw movie ratings introduction (G for everyone, F for family, etc.).

Finally, in 1968, the Production Code was officially abolished.

Dimitri Tiomkin (1894-1979)

; It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

High Noon (1952)

where score was composed before scene cutting. Movie director cut scenes to fit score.

Score’s beat syncs with clock ticking. Scene cuts every score downbeat. Score used Frank Miller’s villain theme to anticipate battle. During battle toward end, Will’s theme represents protagonist, Frank Miller’s villain theme represents villain.

Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975)

composer by age 20 and often supported young composers by performing their lesser-known works.

Herrmann was notably harsh and direct with movie directors about their films’ quality. He joined CBS Radio in 1934, writing radio dramas and conducting the CBS orchestra. Radio in the 1930s was essentially TV before television existed, featuring various dramas (suspense, comedy, etc.) with sound only. Afternoon advertisements targeting housewives often promoted soaps, hence “soap operas.” Herrmann excelled at this music and stayed very busy.

Later, he worked for Mercury Players, owned by Orson Welles, an even younger man. In October 1938, Welles’ radio show adapted H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds, presenting it as a series of “fake news” reports about alien invasion.

Many Americans tuned in after the disclaimer, thinking the news was real. Many were scared; one person even shot someone. This made headlines the next day as “The Night that Panicked America.” Welles was forced to apologize.

Hollywood wanted Welles: if you can cause that much disturbance with radio, you’d make a good movie director. Welles demanded complete control of his films, which was too bold for many studios. Eventually, in 1940, a studio accepted his demands and brought him to Hollywood. Following Welles, that’s how Bernard got into Hollywood.

Citizen Kane (1941)

, two theremins, three electric organs, three vibraphones, two glockenspiels, two pianos, two harps, three trumpets, three trombones, and four tubas.

This very unusual instrumentation pioneered modernism. Definitely not tonal.

Video Example

Scene of alien landing; American soldiers point guns at alien and shoot. Then a “destroyer of worlds” alien appears and starts destroying.

When the alien first lands, music creates a “sound cloud”: music focusing on texture, not themes or melody. Just stationary notes with rich, dark texture from unusual instrumentation. Makes you anticipate something.

A soldier shoots the alien. Sound cloud suddenly stops. Unlike Alien Resurrection, there’s no buildup—it just stops. Even though you were anticipating something, it still shocks you. Sound cloud needs good conclusion; it’s so noticeable you can’t just fade away. Music stops at gunshot.

Then the destroyer alien appears with very rich, dark textural music. Modernist approach.

Not “Standard” Instrumentation

Herrmann’s biggest contribution to film scores was realizing movie music can use “non-standard” instrumentation.

Symphony Orchestra: a standardized performance ensemble. In music, certain instrument sets have become standardized over years. Composers write for symphony orchestras because many such orchestras exist worldwide, so your music can be performed. If you write weird instrumentation, no one can play it.

However, Herrmann realized film scores only need to be played once in recording studios, never again. Thus, he doesn’t need standard instrumentation everyone can play; he just needs instrumentation fitting the scene best.

Beneath the 12-Mile Reef (1953)

and North by Northwest (1959). Herrmann uses standard orchestra and tonal music when they fit well—not always atonal and unusual instrumentation.

Psycho (1960)

, sounding cold. Overall score is dissonant.

Psycho 1: The Money

Marion debates in her room whether to take money and disappear. Short repetitive theme that fractures. Quiet but unsettled—Marion’s discomfort with theft. Theme grows slightly as she decides. Notice sustained string notes without vibrato—very cold.

Almost like film noir era scene: visually small, but music intensifies and highlights inner turmoil.

Psycho 2: Flight

Marion wants to buy a new car since people could track her current one. She buys one but gets called by police; apparently she left her suitcase in the old car. She escapes.

Music enters as she makes her “escape” and does not change. Initially seems to play her fear of being caught. However, she starts thinking she’ll get away and smiles evilly. As she becomes evil, music seems to play her fall to the “dark” side. Throughout this transformation, music doesn’t change; it just creates mood.

Psycho 3: Norman’s Theme

After brief chat between Marion and Norman, Norman’s theme starts as he watches her walk to her room.

Theme made of only semitones, creating uncertainty since semitones are very close; you can’t tell “which note is dominant.” Definitely not major scale. Gives weird feeling of “where will this cue start or end.”

As he looks through peephole to spy on Marion’s room, violins play “harmonics” (泛音). Uncomfortable to listen, no emotion.

Psycho 4: The Shower

Scene of Marion being stabbed in shower. No music until attack. No tonality at all. Strings were “shrieking”—very violently striking strings with bow.

As murderer runs away, music played is actually Norman’s theme with semitones after thematic transformation. This hints the murderer is actually Norman. Also illustrates that despite modernism, old techniques like thematic transformation still work.

Trivia: Censorship people demanded film censoring, especially shower scene bits. Alfred Hitchcock waited three days, sent exact same film back saying “yeah good advice we’ve fixed it.” Executives said “yeah that’s much better great film.” Good example studied in film school. No direct stabbing shots on body, just implied through shots.

Hitchcock initially insisted no music for shower scene. When vacationing for a weekend, Herrmann said “yeah let’s add music because Hitchcock’s dumb.” Monday Hitchcock returned saying “yeah with music is better haha.”

Fake blood didn’t look right in black and white, so they used chocolate sauce instead.

Unfortunately, Psycho was the collaboration peak between Herrmann and Hitchcock. Herrmann was very opinionated and hated pop music in films. Hitchcock asked him to score Torn Curtain (1964) using pop music. Arguments heated up and Herrmann decided never to collaborate with Hitchcock again.

Bitter, Herrmann moved to Europe, making music for Fahrenheit 451 (1966), directed by Truffaut—a sci-fi dystopian film.

His last movie was Taxi Driver (1975). Herrmann returned to the U.S. to make this film but passed away during filming due to heart attack. Credits were dedicated to him.

The 1960s

, “generational gap” with most young people disagreeing with previous generations and wanting to break the status quo. Young people were major movie audiences.

Films in the 1960s:

- Cultural revolution of late 1960s resulted in films with strong irony and cynicism

- End of Studio System: movie industry workers became freelancers and independent productions, causing movie costs to explode

- When tested: Studio system started collapsing in the 1950s, finished collapsing in 1960s

- While orchestral scores continued, big orchestras weren’t used as often: more expensive to shoot movies, so smaller ensembles were used, or just popular music. This was also when popular music exploded—The Beatles era.

General 1960s film music observations:

- Continuing growth of popular music influences

- Continuing growth of dissonance, atonality, following modernism

John Barry (1933-2011)

all James Bond movie-songs using his pop music background.

John Barry’s Orchestral Music

does one thing. His style is clear, tonal, melody-focused music showing pop music influence.

John Barry exemplifies how pop music started influencing film music.

Jerry Goldsmith (1929-2004)

. However, he disliked academic courses except Rózsa’s, so dropped out for community college.

He started at CBS radio in 1950, initially hired as typist even though he couldn’t type. They didn’t hire him as music composer. He bribed typist colleagues to do his work while sneaking into the music department. Friends there secretly let him make music.

One day an executive found out: “this music nice, who made it?” His friends said “Jerry Goldsmith.” That’s how Jerry got to CBS’s music department.

By early 1950s, TV was overtaking radio, so Jerry jumped to CBS TV shows instead of radio shows. First composer we discuss who came from TV show music. He did music for The Twilight Zone, though not the main theme.

His TV work gained attention, and he started writing film music in 1957. Alfred Newman recommended him to Universal music. Goldsmith’s famous work: The Universal Fanfare.

:

- “March theme”: very tonal, used for military marching

- Chorale: Patton has strong Christian beliefs, believing God blesses him for battle victories. Recall from Apollo 13: chorale is sacred church song type. Simple melody in small steps because chorales were meant for laypeople to sing

- “Call to war” theme: Patton believes in reincarnation (转世), getting reincarnated as needed heroes. Theme features trumpet solo with 3 notes, but trumpet is echoed repeatedly. Echo reflects Patton’s belief in constant reincarnation. 1960s was when music studios gained much more technology, including echoes. Use of electronic processing on orchestral instruments

First march theme is very tonal. Second chorale is fairly tonal. Third call to war theme is fairly modernist.

Patton Ex 1: North Africa

“Sound cloud” as they arrive at battlefield, creating tension. Note electronic echo use on trumpet—example of “call to war” theme.

We are back to a composer making music matching scenes very closely. When Patton says “two thousand years ago,” chorale plays reflecting his Christian belief. His next line “I was here” triggers “call to war” theme reflecting reincarnation belief.

When chorale plays, it overlays the sound cloud, creating weird feeling.

Patton Ex 2: Advance in Europe

Montage blending all three themes. When shot switches to Patton marching to Berlin, march theme plays. When commanding officers discuss Patton, chorale plays, reflecting Patton as God-sent hero. When scene switches to German side where Germans write casualty numbers, call to war theme plays.

Most prior films portrayed Germans and Japanese as absolutely evil, U.S. generals as absolutely good. This film shows empathy for Germans and protagonist Patton also has many flaws.

Patton demonstrates Jerry Goldsmith’s comfort writing both tonal and modernist music.

Planet of the Apes (1968)

, mixing bowls, thunder sheets (metal sheets sounding like thunder). Uses prepared piano: piano with objects on strings changing texture and sometimes pitch. Putting screws at certain string positions, ping pong balls, etc.

Lots of electronic processing on film music, like echoes. This is Jerry Goldsmith’s big contribution: using electronic processing in film music.

Planet of the Apes Ex 1: The Crossing (Part 1)

Scene of astronauts just landing on planet of apes, unsure where to go. No clear music organization—more like “sound” than music. Uses electronic echo, metal thunder sheets.

Planet of the Apes Ex 2: The Crossing (Part 2)

Compared to just “sound,” music is more organized with clear melodic structure. Melodic structure uses 12-Tone technique: play 12 notes, 3 at a time, so 4 sets of 3 notes. In fact, entire score themes are just these 12-note patterns.

Arnold Schoenberg (2nd Viennese School) developed 12-Tone technique. Schoenberg is Raksin’s teacher. He and a group of musicians, called the “2nd Viennese School,” developed this technique.

The idea: traditional tonal approach prioritizes white keys over black keys. He wanted music equally valuing all 12 semitones in chromatic scale.

Thus, 12-tone technique says you can only use the same note twice after using all other 11 semitones. This forces equal weight to all 12 semitones.

In 1923, “tone rows” were introduced: , music is chaotic—”chirping” woodwinds, log drums; more “primitive” sound.

Music characterizes humans and takers very differently, not through tonality vs. atonality but through “organization” vs. “chaos” feeling.

Throughout scene, music switches rapidly between humans and takers; Jerry Goldsmith follows scenes very closely.

Planet of the Apes Ex 4: No Escape

Protagonist tried escaping apes’ prison but was caught. He couldn’t speak due to throat injury. When captured in net, he spoke for first time, shocking apes who thought he couldn’t speak.

At this moment, a long, loud tonal note plays. This is the only time a tonal note plays in entire score because this is the only time protagonist is in control by shocking apes.

Planet of the Apes Ex 5: The End

At ending, protagonist found proof humans existed before apes on Earth, but ape doctor bombed it to preserve ape faith (propaganda).

12-tone theme plays, sounding more comfortable now because we’ve heard it many times. Protagonist ends in despair; movie concludes.

No music at end, just waves, leaves dramatic image in your head. If dramatic music ended instead, it reminds you “it’s a movie” and provides relief. Without music, it doesn’t pull you out, making you resonate with human race despair.

scores seemed outdated and irrelevant.

John Williams (1932-Present)

. He’s also a good jazz pianist and writes music daily.

Went to do military music in Newfoundland. Newfoundland wanted him to write music for a tourism film—that’s how he entered film music. Made music for popular TV shows in late 1950s. We discussed how after TV became popular, writing TV show music became the “academy” for film music.

Popular TV series: Lost in Space, Land of the Giants, Gilligan’s Island. Miklós Rózsa was an early mentor.

The Sugarland Express (1974)

—folk music, southern style.

Jaws (1975)

by Igor Stravinsky. Steven wanted “pirate music,” but Williams made this simple but effective theme with repeated notes.

However, lots of orchestral, tonal music like Korngold was used—Neo-romantic style.

Trivia: The mechanical shark didn’t work in the first half, so they couldn’t show the shark until the second half. However, this made the movie better because “not showing the monster” actually makes it scarier. Without the real shark, music was critical for building suspense and mood.

Video Example 1: Get Out Of The Water

First shark appearance on beach, killing tourist. Underwater shots as shark’s POV seeing people’s legs.

Shark theme enters with underwater shot, rising in intensity before attack. Modernism-like strings (like Psycho) during Brody’s (sheriff’s) reaction. Brody sees blood in ocean. Camera physically moves toward sheriff’s face while zooming out simultaneously—cool effect.

During this zoom shot, music has very modernistic, dissonant strings like in Psycho. Theme fades away, implying shark departure.

Video Example 2: The Fishermen

Fisherman on dock with underwater baits. Shark theme enters as tire (with food bait) is pulled to sea, then grows in intensity. Shark pulls hard on bait, destroying dock with fisherman on it.

Dock changes direction while fisherman swims to shore, suggesting shark pursuit. Fisherman barely makes it back; theme fades, suggesting shark departure.

Video Example 3: He Made Me Do It

In previous attacks, setup was always: underwater shot, people screaming, shark theme builds up. In this scene, same setup happens except shark theme wasn’t played. To emphasize shark theme absence, John even included source music of band playing on beach.

Turns out attack is prank with kids making shark fin-looking object. This gives audiences feeling that shark is only real if shark theme plays.

Video Example 4 (A): You’re gonna need a bigger boat

The rug pull: sheriff Brody goes on boat with Quint (captain) to catch shark. But no music when shark suddenly appears, creating visual jumpscare.

Audience got impression shark appears iff shark theme plays. Thus, no shark theme but shark appearance gives jumpscare. This makes rest of film scarier: now shark can appear anytime.

Now that audiences are scared out of their comfort zone (only scary when music comes), Brody says famous line “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

Jumpscare shot uses classic “negative space”: main character on screen side with nothing at center, setting up something scary to happen at center.

Video Example 4 (B): The Barrel

They decide shooting harpoon at shark with attached empty barrel, thinking floating barrel will prevent shark submersion.

Shark theme builds after first sighting. When whole shark passes boat, new theme appears with wondrous/amazement feel.

Quint’s theme plays on top (as fugue): highly structured, deliberate, focused (as captain). Hooper’s theme (oceanographer) as he tries photographing shark: childlike, wonder, excitement, very tonal.

Theme builds to harpoon shot (Quint trying to capture shark). Arrow hits; music feels like “pirate music,” very romantic and Korngold, giving excitement and uplift.

At end, barrel disappears underwater unexpectedly, suggesting shark is much stronger than thought. Pirate music gets lower and slower, bringing scene to conclusion—good pacing example. Similar to how Korngold concluded Sea Hawk scenes. After all modernism, music sounds like it could be straight from 1930s.

Jaws was major hit; everybody, including audiences, realized John Williams’ music importance. People started singing shark theme whenever indicating danger or someone messing up silly. Williams was first composer having music famous beyond films.

Star Wars (1977)

.

George Lucas (director) wanted Korngold-sounding score, so Spielberg recommended Williams to Lucas. Lucas wanted literally Korngold’s style—temp tracks were Korngold’s music.

Williams composed for standard orchestra with completely tonal themes and thematic transformations—totally Korngold. However, when needed, some score parts can be modernist, like Sand people’s theme.

John Williams’ style:

- Neo-romantic, influenced by traditional Wagner/Korngold and recent modernist styles

- Williams never used contemporary pop music but was capable of jazz-influenced styles

John Williams is perhaps the most famous film composer, with Hans Zimmer being only recent competition. Why?

, and they’ve been playing it for 40 years.

That’s why John Williams is this famous.

1980s

The 1980s operated under John Williams’ shadow. All film scores were strongly influenced by Williams’ work. Composers moved back to orchestra as starting point. Neo-Romantic fused with modernism elements became dominant film music style. Main themes tend to be tonal.

Notable composers becoming prominent: James Horner, Michael Kamen, and Alan Silvestri.

Back to the Future (1985)

in 1978.