A Radio-Edit of Pop Music History

Published:

I am an avid music history enthusiast who spends an embarrassing amount of free time watching documentaries about famous (and delightfully infamous) bands and figures, while attempting to listen to and reproduce their music with varying degrees of success.

Fortunately, one of the finest courses offered at the University of Waterloo is a course on modern pop music history, taught by the accomplished musician and professor Simon Wood.

This document, adapted from my hand-written notes for the course, presents a journey through western popular music history. We’ll trace this winding path from the origins of Blues and its enduring African retentions that still pulse through modern pop music, through the swinging Big Bands of the post-WWII era, country, R&B, Rock, Funk, Psychedelic, Metal, and finally to the emergence of Hip-Hop in the 1980s.

I wish to dedicate this document to all the extraordinary creative souls who have trancended time and circumstance, whose voices have carried stories of struggle and triumph, and whose music continues to move, inspire, and light up my days and nights.

The Post-War Musical Landscape

End of WWII (1945)

As the dust settled from the greatest conflict in human history, the U.S. found itself in a peculiar position: victorious, prosperous, and ready to dance. From 1939 to 1945, the musical landscape was dominated by “Big Bands”, featuring saxophones, trombones, trumpets, and the occasional vocalist who was more decoration than main attraction.

These ensembles were designed specifically for dancing. Stars like Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, and Count Basie ruled the airwaves, creating the sound for a nation that desperately needed to move its feet after years of rationing and worry.

But as 1945 rolled around, something interesting happened: the focus began shifting from the band to the individual vocalist. It was as if America collectively decided that while orchestras were nice, what they really wanted was someone to sing directly to their hearts.

The Three Musical Tribes of 1945

By 1945, the American music industry had neatly categorized itself into three distinct markets, based on their intended audiences. It was musical segregation with a business plan:

- Popular (or “Pop”): For white, middle-class, urban, northern audiences

- Race: For Black audiences

- Hillbilly: For working-class white, rural, southern audiences

This categorization tells us more about America’s social divisions than its musical preferences, but it’s where our story begins.

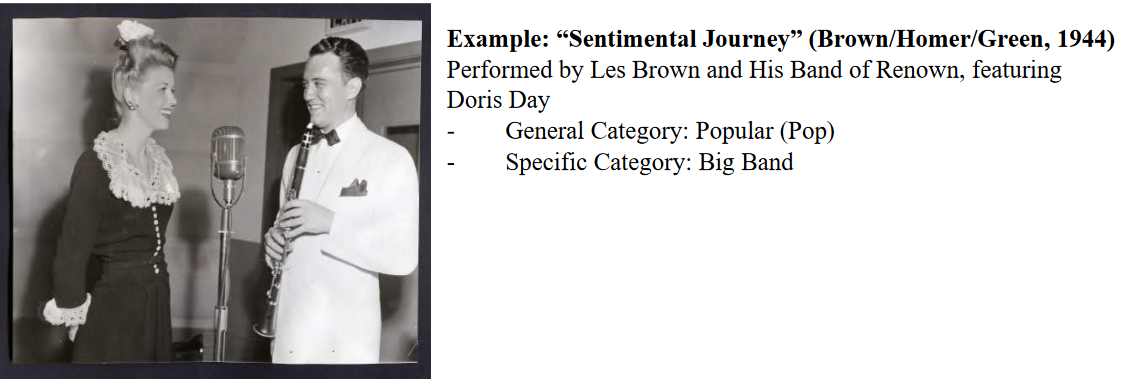

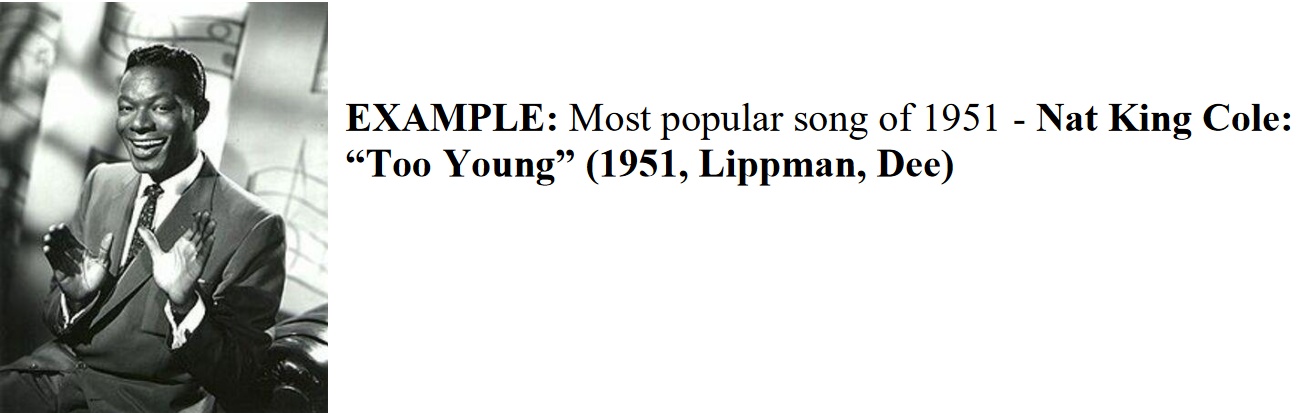

Big Band (Pop) Example: Sentimental Journey (Brown/Homer/Green, 1944)

To understand this transitional moment, let’s examine a song that perfectly captures the end of the Big Band era. “Sentimental Journey,” performed by Les Brown and his Band of Renown with Doris Day as vocalist, demonstrates how the spotlight was beginning to shift:

- Still designed for dancing with that unmistakable clear rhythm

- Vocal comes in late - the band still gets to show off first

- Smooth, controlled vocals - no distortion, no rough edges, just pure professionalism

- The vocalist is featured, but not yet the star - a preview of things to come

Musical Examples from Each Category

Now let’s explore what each of these three musical categories actually sounded like:

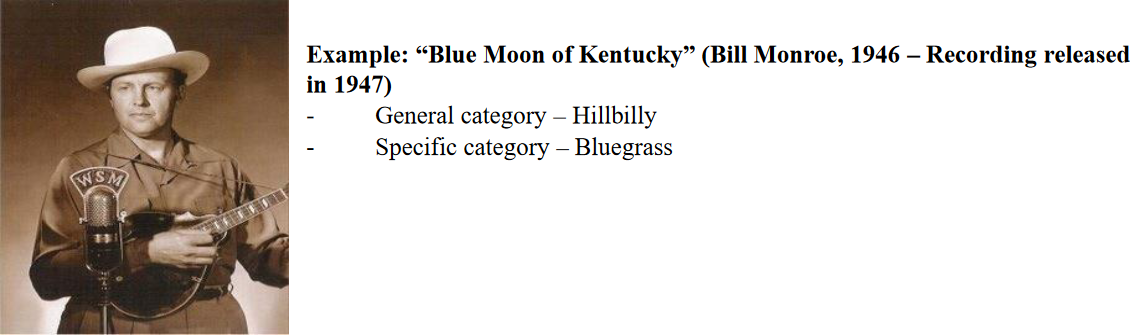

Hillbilly Example: Blue Moon of Kentucky (Bill Monroe, 1946)

Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” gives us a perfect snapshot of what “Hillbilly” music offered its audience:

- No big band instruments: just solo instruments like acoustic guitar

- Complete focus on the vocalist: no waiting around for instrumental solos

- Nasal cavity resonance instead of chest voice. A distinctly rural sound

- Emotional distance: even when singing about heartbreak, there’s a certain stoic restraint

This song would later become famous for an entirely different reason, but we’ll get to that story soon.

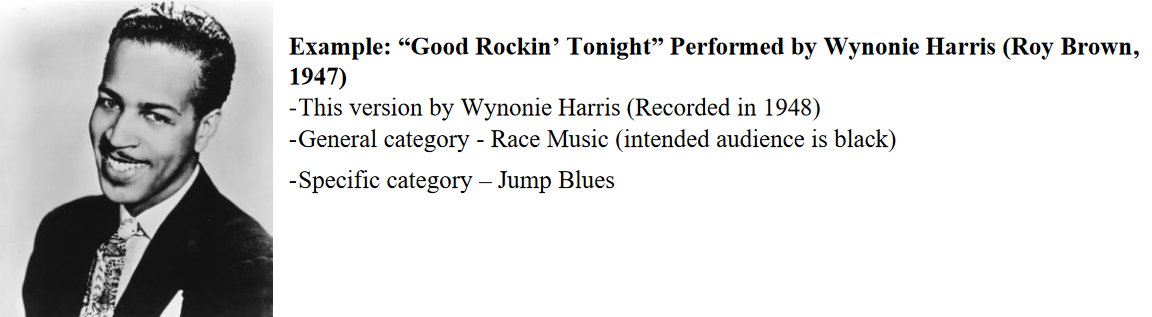

Race Example: Good Rockin’ Tonight (Wynonie Harris, 1947)

Example of “Race” music:

- Similar to Big Bands in its dance-focused energy and clear rhythm

- But crucially different. Fewer brass players, more focus on the vocalist

- Less smooth vocals, lots of intentional distortion and grit

- Raw energy that would soon change everything

This song, originally written by Roy Brown, represents a bridge between the polished Big Band sound and something much more revolutionary that was brewing.

The Business of Making Music

How the Industry Actually Worked

By 1945, the music industry was selling two main products: sheet music and recordings. For most of the previous century, sheet music had been king; however, after World War II, recordings began to dominate, fundamentally changing how music was consumed and, more importantly, who could make money from it.

The Foundation: Copyright and the Middle Class

The entire modern music industry rests on a foundation laid between the 1790s and 1830s, when copyright laws were amended to cover sheet music. Suddenly, musicians could profit from the general public rather than just wealthy patrons.

At the same time, the Industrial Revolution fostered the growth of the middle class, who could now afford pianos, creating a market for music that could be played at home. The music popular at the time was the “Victorian Ballad”, and particularly the subcategory: Parlour Songs.

Victorian Ballads and Parlour Songs

- Popular during the 1800s

- Performed by daughters in middle-class households, to “show off” their education and wealth

- Targeted at urban, middle-class, white, northern audiences

A Classic Example: “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms” (Thomas Moore, early 1800s)

Musical Structure:

- AABA format: a structure that would dominate popular music for decades

- Piano accompaniment: showing off the family’s investment in culture

- Controlled, smooth vocals: no emotional outbursts allowed

Lyrical Themes:

- Loyalty, honesty, control, restraint: all the virtues a proper Victorian family wanted to display

- Idealized romance: love that’s pure, eternal, and completely unrealistic

The lyrics follow that classic AABA pattern:

Believe me, if all those endearing young charms, That I gaze on so fondly to-day, (a) Were to fade by to-morrow, and fleet in my arms, Like fairy-gifts fading away, (a) Thou wouldst still be adored, as this moment thou art, Let thy loveliness fade as it will, (b) And around the dear ruin each wish of my heart Would entwine itself verdantly still. (a)

The Birth of the Hit Song: “After The Ball” (Charles K Harris, 1891)

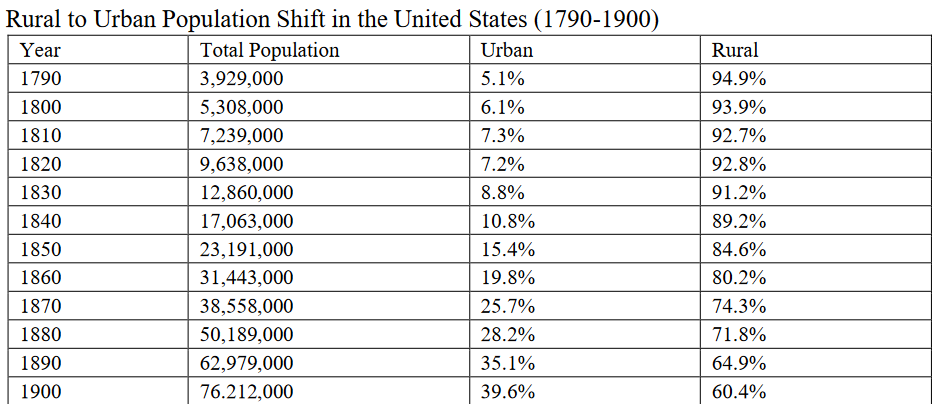

And then came the song that changed everything. “After The Ball” became the first genuine “hit song,” selling over 5 million copies, a staggering number for the 1890s. It was still technically a Parlour Song, but its success revealed something important: America was urbanizing rapidly, creating concentrated populations of potential music buyers.

The timing was perfect. By 1891, more people had moved from rural areas to cities, creating the critical mass needed for a true mass market. “After The Ball” proved that the right song could reach unprecedented numbers of people.

The Tin Pan Alley Revolution

The massive success of “After The Ball” gave birth to Tin Pan Alley (TPA), which became the center of the American music industry in Manhattan, New York City. By the 1920s and 1930s, this musical ecosystem included 21,000 publishers and 36,000 composers.

The Division of Labor Revolution

TPA introduced something revolutionary: the division of labor. Instead of one person doing everything (as in rural folk traditions), TPA separated the roles:

- Composers wrote the music

- Lyricists wrote the words

- Publishers handled the business

- Performers sang the songs

This industrial approach to music-making would define popular music for decades to come.

The TPA Musical Formula

TPA wasn’t just a place; it created a distinctive musical style designed for maximum commercial appeal:

- Easy to play and sing: accessible to amateur musicians and singers

- Idealized romance themes: focusing on the beginning and end of relationships

- AABA musical structure: with the B section providing contrast before returning to the familiar A, creating a sense that the song could continue forever

This formula was so successful that it became the template for American popular music.

TPA Example: “Somewhere Over The Rainbow” (Arlen/Harburg, 1939)

To see the TPA formula in action, “Somewhere Over The Rainbow,” performed by Judy Garland in “The Wizard of Oz” (1939), is famous enough that I do not need to provide a video clip.

The song demonstrates everything TPA stood for: AABA structure, accessible melody, and that satisfying return to the A section that makes you want to hear it again.

The African American Musical Revolution

The TPA formula is great, but it is certainly not the formula today. The missing ingredient are the African Retentions, specifically, the Western African Retentions, imported to American in a shameful way.

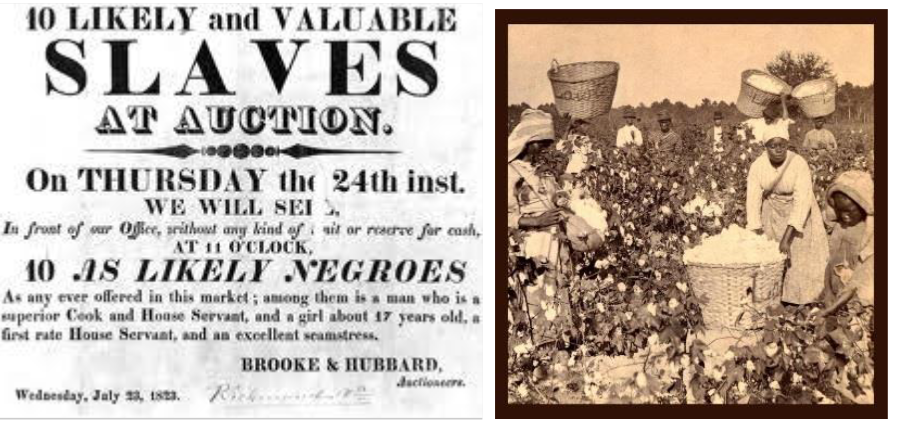

The Foundation: North American Slave Trade (1619 - 1865)

The story of American popular music cannot be told without understanding the profound impact of the North American slave trade, which lasted from 1619 to 1865.

While we have no recordings from the slavery era (recording technology didn’t exist yet), we do have detailed accounts from contemporary observers who documented these musical traditions. What they described would become the foundation for virtually every form of American popular music that followed.

Work Songs: Echoes of the Past

“Old Alabama” (1947)

This recording offers us a window into musical traditions that stretch back centuries. While “Old Alabama” wasn’t performed by enslaved people—the slavery era ended in 1865, well before recording technology existed—it was sung by a prison chain gang in 1947. According to a famous author who has heard of enslaved people singing, the two have many similarities.

The recording captures workers chopping a fallen tree, and you can hear the steady rhythm of axes against wood.

Work songs operated as sophisticated musical systems that served multiple purposes:

- A song leader drew from a “floating pool of verses,” mixing and matching familiar song fragments

- Call and response - Workers would join in once they recognized the verse being sung

- Skilled leaders could sense when workers were tiring and adjust the tempo accordingly

- Workers even humor during difficult labor. These songs transformed grueling work into something more bearable.

Understanding Folk Music

Work songs represent a broader category called folk music, which has some distinctive characteristics:

- Performed by amateurs - people who don’t make their living from music

- Tradition over innovation - folk musicians typically sing what their parents and grandparents sang

- Lacks self-consciousness - there’s no attempt to stand out or be different; the focus is on preserving tradition

This “lack of self-consciousness” becomes important later when we see how professional musicians began to deliberately innovate and create distinctive styles.

African Retentions: In The Roots of American Popular Music

Most current Western popular music can trace its origins back to West African musical traditions, brought to America through the slave trade. It introduces 3 key elements to the west:

1. Percussive and Distorted Timbres

- Percussive sounds: music that hits you with impact, like the sharp articulations you hear in modern rap

- Intentional distortion: while European classical music prized “pure” tones, West African traditions embraced distortion as a way to express emotional intensity and energy overload

2. The Power of the Riff

- Riffs are short, self-contained musical phrases that repeat as the foundation for longer compositions. Think of the “beat” in modern pop music, that’s essentially a riff

- Riffs vs. Motifs: A classical motif (like the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony) constantly evolves and changes, while a riff stays the same, creating a hypnotic repetition

3. Call and Response

- This is the musical equivalent of a conversation. In European classical music, information flows one way: composer → conductor → audience. In African-derived traditions, information flows both ways: performer ↔ audience. You can hear this today when a pop singer shouts something and the crowd responds.

The Birth of the Blues

The End of Slavery and New Beginnings

The American Civil War (1861-1865) fundamentally changed the nation’s social and musical landscape. The conflict arose from deep divisions: the North sought to abolish slavery, while many Southern states depended heavily on enslaved labor for their economic survival. When the war ended in 1865, it marked not just the conclusion of slavery, but the beginning of a new chapter in American music.

The Post-Slavery Era: Challenge and Innovation

The period following emancipation brought both tremendous challenges and remarkable musical innovation:

Institutionalized Resistance Despite slavery’s legal end, many Southern states responded with discriminatory laws designed to maintain racial hierarchies. These “Black Codes” severely restricted the rights and movements of formerly enslaved people.

The Great Migration Begins Seeking better opportunities, many African Americans began moving from rural areas to cities. While they often faced exclusion from white-dominated industries, this migration led to the formation of vibrant Black communities, businesses, and musical scenes.

Urban Musical Innovation In cities, new musical forms began to emerge in the late 1800s, including Ragtime and early Jazz. The music of composers like Scott Joplin demonstrated how African American musical traditions could flourish in urban environments, eventually influencing mainstream popular music.

Country Blues: Music of the Road

While cities saw the rise of Ragtime and Jazz, rural areas developed their own distinctive musical response to post-slavery life: the Country Blues.

Country blues was typically performed by solo male vocalists accompanied by acoustic guitar. These traveling musicians moved from place to place, sharing songs and stories with communities that understood their experiences.

Blues vocals carried a distinctive “sad” feeling, what scholars often call “lament” or “songs of complaint.” Yet within this sadness lay humour and resilience.

The lyrics of country blues reflected the realities of life for many African Americans in the post-slavery era:

- Travel and movement: reflecting the wandering lifestyle of many performers

- Economic hardship: the constant search for work and opportunity

- Personal relationships: love, loss, and human connection

- Social commentary: observations about life in a changing America

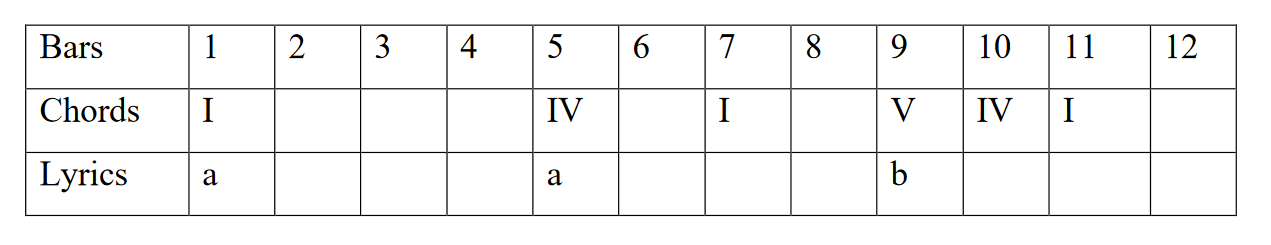

The Blues Formula: A Musical Architecture

The blues developed a remarkably specific and enduring musical structure that would influence popular music for generations to come (I love the blues scale!):

The 12-Bar Structure Blues songs typically follow a 12-bar (or 12-measure) pattern that creates a satisfying musical journey. This structure became so fundamental that musicians still use it today.

Blues lyrics follow a distinctive pattern:

- First line (A): states the problem or situation

- Second line (A): repeats the first line, giving it emphasis

- Third line (B): provides resolution, commentary, or a twist

Like the work songs before them, blues featured call and response, but now between the singer’s voice and the guitar, creating an intimate musical dialogue.

This 12-bar blues structure was remarkably specific, dictating not just the number of measures, but also which chords to play and how to structure the lyrics. The pattern repeats throughout the song: first 4 bars for the “A” lyric, next 4 bars for the repeated “A,” and final 4 bars for the “B” resolution.

No other musical form was quite this precise, yet it proved flexible enough to accommodate countless variations and personal interpretations.

The Recording Gap While blues music emerged in the 1890s, the first rural blues recordings weren’t made until the 1920s. This three-decade gap occurred because the recording industry was largely controlled by white-owned companies who initially showed little interest in rural African American music.

The First Recorded Blues: “Travelin’ Blues” by Blind Willie McTell (1929)

When the recording industry finally began documenting rural blues in the 1920s, one of the earliest and most representative examples came from Blind Willie McTell, a Georgia-born musician whose “Travelin’ Blues” perfectly captured the essence of the form.

A Perfect Country Blues Example

The song demonstrates the classic A-A-B lyric structure:

Mr. Engineer, let a man ride this line. (A) Mr. Engineer, let a poor man ride this line. (A) I wouldn’t mind it fella’, but you know this train ain’t mine. (B)

McTell’s lyrics embody the central themes of country blues: a man seeking transportation to find work and opportunity. The train represents both literal movement and the hope for a better life.

While McTell was a professional musician making his living through music, his approach remained rooted in folk tradition. He wasn’t trying to create a distinctive personal style or stand out from other performers. Instead, he focused on preserving and sharing the musical traditions of his community. This lack of “self-consciousness” dictates his performance as “folk”, even as it was being commercially recorded.

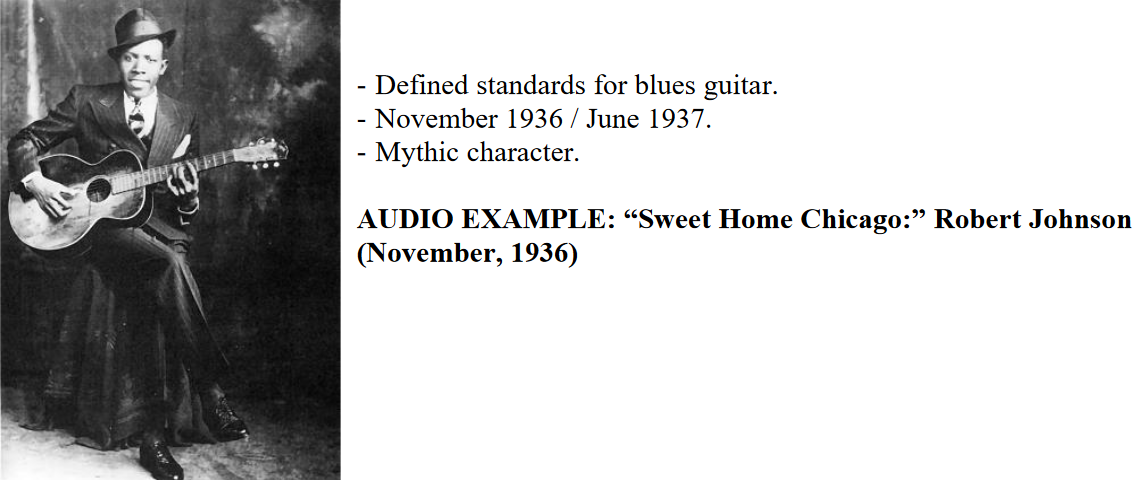

Robert Johnson: The Blues Transform

A few years after McTell’s recording, another blues musician emerged who would fundamentally change how we think about the genre. Robert Johnson (1911-1938) represented a new kind of blues artist, one who brought artistic self-consciousness to a traditionally folk form.

Johnson’s recording career was remarkably short: just two sessions in November 1936 and June 1937. Yet in that brief time, he created music that would influence generations of musicians. His life ended tragically in 1938 under mysterious circumstances, he was believed to have been poisoned, though the details remain unknown.

Stories grew around Johnson that added to his mystique. According to legend, he had been an unremarkable guitarist who disappeared for several years, only to return as an extraordinary musician.

The fact that he passed away at the age of 27 marks him as a member of the “27 Club”, an unusually long list of legendary musicians who died at the age of 27.

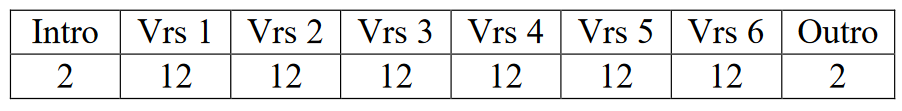

Ex: “Sweet Home Chicago” (November 1936)

Johnson’s approach marked a significant departure from traditional folk blues. His recording of “Sweet Home Chicago” demonstrates a new level of artistic self-consciousness:

The song follows the classic 12-bar structure, with lyrics that exemplify the A-A-B pattern:

Ooh, baby don’t you want to go? (A) Ooh, baby don’t you want to go? (A) Back to the land of California, to my sweet home Chicago (B)

Johnson’s performance was clearly self-conscious:

- Dynamic awareness: carefully controlling volume and intensity throughout the song

- Structural planning: thoughtful introductions and conclusions

- Guitar-vocal dialogue: sophisticated call and response between his voice and instrument

Unlike McTell’s preservation of tradition, Johnson was clearly trying to create something distinctive and memorable. This marked the beginning of blues as an art form rather than simply folk expression.

Johnson’s recordings were marketed primarily to African American audiences, representing the emergence of what the industry called “race music”, recordings specifically produced for Black listeners. This category would soon evolve and eventually help transform all of American popular music.

A Technological Turning Point

As the story of American popular music unfolds, technological change plays a crucial role. By the mid-20th century, new inventions would radically alter how music was produced, distributed, and consumed. From fragile wax cylinders to powerful radio broadcasts and the dawn of television, these innovations reshaped the entire music industry and helped propel new genres to national attention.

Mechanical Reproduction: From Edison to the Record Industry

The journey began in 1877 when Thomas Edison introduced the phonograph. Using a wax cylinder to capture sound, Edison created the first device capable of mechanical sound reproduction. Though fragile and limited in fidelity, it marked the beginning of an industry.

By 1910, disks had overtaken cylinders as the preferred format. With the introduction of the 78 rpm standard, music could now be recorded, distributed, and played back with much greater consistency. These innovations laid the groundwork for a mass-market music industry.

In the early days, most recordings were of Tin Pan Alley songs. Rural southern white music and African American music were generally excluded due to industry biases, cultural chauvinism, and concerns about marketability in less urbanized areas.

The Rise of Commercial Radio

In 1920, another major development arrived: the birth of commercial radio. Funded by advertising, radio became a new cultural force almost overnight. In January 1922, the U.S. had just 28 stations; by December of that year, there were 570.

As stations expanded, large corporations purchased and linked them into national networks, such as NBC, CBS, and Mutual. By 1928, NBC Red became the first coast-to-coast network. Radio stations, now broadcasting the same programs nationwide, created a shared cultural experience.

This shift from regional to national broadcasting reshaped music consumption. A hit song could now become a household staple overnight. Records, however, suffered initially—radio offered unlimited music for a one-time cost, while records required ongoing purchases and upkeep.

Saving the Record Industry: Perry Bradford and Ralph Peer

With records on the brink, innovation came from an unexpected source. In 1920, Okeh Records was preparing to record a song titled “Crazy Blues,” but the scheduled artist fell ill. Perry Bradford suggested replacing the singer with a local Black woman, Mamie Smith.

Ralph Peer, the producer, agreed. Mamie Smith’s performance became the first serious recording by a Black vocalist—and a surprise hit. It revealed untapped markets: not only were there African American listeners eager for this music, but even white urban audiences were buying it.

Realizing that radio was not catering to these underserved markets, Peer began recording what radio ignored: music from African Americans and rural southern whites. Thus, the record industry introduced two new categories:

- Hillbilly: for southern white music

- Race: for Black American music

This pivot preserved the record industry and introduced styles that would soon dominate popular music.

Musical Examples of New Categories

- Hillbilly Example: Uncle Dave Macon and the Fruit Jar Drinkers, “Carve That Possum” (1927)

- Race Example: Carr and Blackwell, “How Long Blues” (1928)

Though “How Long Blues” doesn’t strictly follow the 12-bar format, it carries the essence of the blues, now adapted for urban environments. The presence of piano and multiple musicians allowed innovations like guitar solos—though at this stage, acoustic guitars struggled to compete with louder instruments like the piano. This drove the eventual transition to electric blues.

By the late 1920s and 1930s, records and radio coexisted, with live performance still dominating radio. But a new technological breakthrough on the horizon would again shift the balance.

The Television Era and Beyond

Following World War II, television emerged as a powerful cultural force. First demonstrated in 1927 and largely dormant during the war years, commercial broadcasting began in 1939. By 1945, there were just six stations; a decade later, there were over 400.

As major networks transitioned to television, they sold off their radio licenses, making radio more accessible to independent owners. This allowed for a broader range of programming—including music tailored to Black audiences.

Black Appeal Radio and Rebranding

In 1948, WDIA Memphis began airing exclusively Black music, tapping into a loyal and growing market. By 1954, 200 radio stations followed suit. To broaden appeal, industry insiders rebranded genres:

- Race Music became Rhythm and Blues (R&B)

- Hillbilly became Country and Western

This allowed for greater crossover into mainstream markets, particularly among the children of the post-war baby boom.

The Baby Boom and Youth Culture

Economic prosperity meant more teenagers had leisure time. This “extended adolescence” created a new youth market hungry for more exciting, energetic music than the safe, middle-of-the-road pop played for housewives.

Enter Jump Blues and Gospel-inspired R&B:

- Jump Blues: Evolved from Big Band and city blues. Fast-paced, danceable, and smaller in ensemble size.

- Gospel Influences: Brought to secular music by artists like Ray Charles, who fused gospel energy with R&B aesthetics. Songs like “I’ve Got A Woman” (1954) introduced stop-time and expressive saxophone textures.

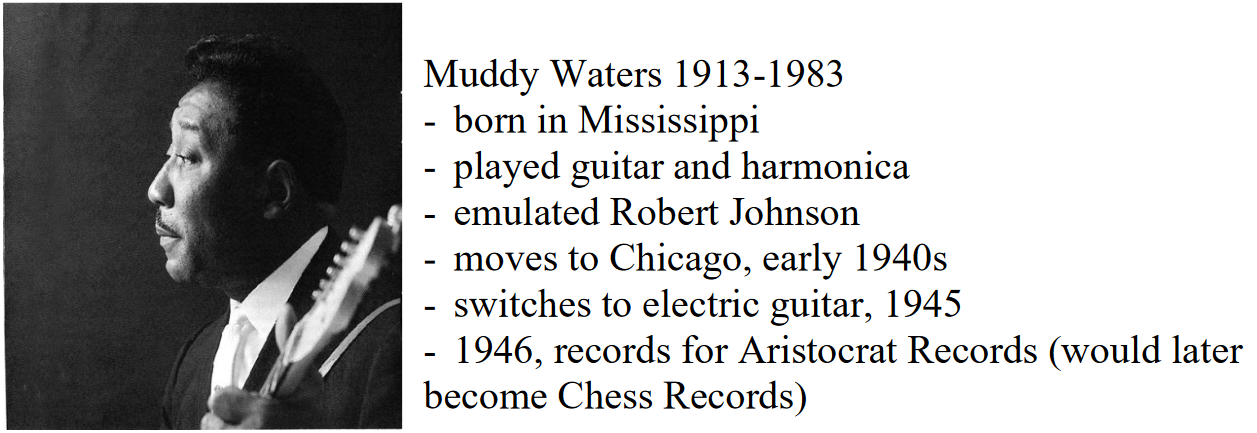

The Electrification of the Blues

Artists like Muddy Waters brought blues to the city and adapted it to new environments by using electric guitars. This innovation matched the genre’s expressive distortion with the new sonic power of electric amplification.

His recording “Hoochie Coochie Man” (1954) maintained ties to rural blues while modernizing the sound with electric instrumentation and modified 12-bar structures.

Chart Crossovers and the Moral Panic

By the early 1950s, some R&B songs were charting on Pop lists, introducing Black artists to white teenagers. But this triggered a backlash among conservative parents, leading to a wave of sanitized cover versions by white artists.

Cover Versions and Cultural Sanitization

Songs like Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” (1955) were covered by Pat Boone in a toned-down version. The original’s intensity and rhythmic drive were replaced with polished restraint—yet Boone’s version charted higher on Pop.

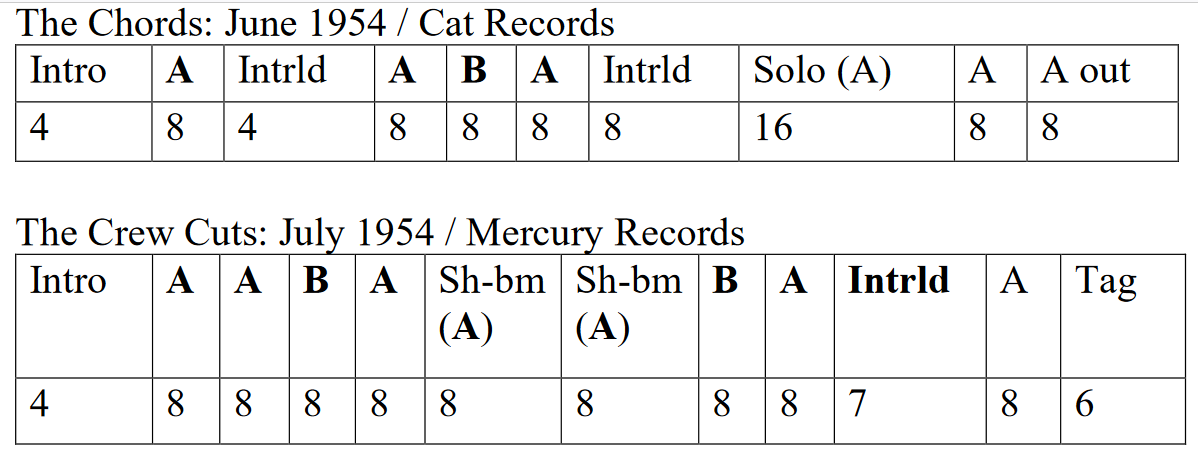

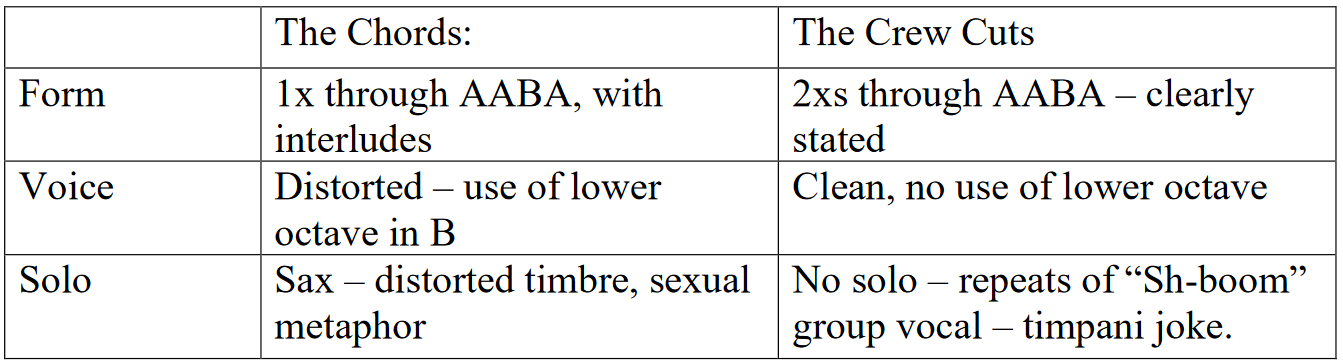

Another example: “Sh-Boom” by The Chords (1954), a soulful, complex R&B track, was transformed by The Crew Cuts into a peppy, safe version that stripped away sexual energy and replaced saxophones with timpani.

While legal under copyright law, these covers exposed the racial inequities in the music industry. Record companies, rather than driven by overt racism, often acted out of profit motives—but their actions still marginalized original Black artists.

This practice faded after 1956, as a new style gained dominance: Rock ‘n’ Roll—a hybrid of pop, country, and R&B that targeted teenagers across racial lines.

Next, we’ll explore how Rock ‘n’ Roll became a cultural revolution, propelled by groundbreaking artists like Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and others who bridged racial divides and transformed the soundscape of youth culture.

The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll

As we transition into the next phase of pop music’s evolution, we witness the emergence of Rock ‘n’ Roll. This genre arose from the fertile cross-pollination of pop, country and western (C&W), and rhythm and blues (R&B), forming a new sound aimed directly at the youth of 1950s America. It was both Black and white in its origins and appeal, and its rise signaled a new, integrated cultural wave.

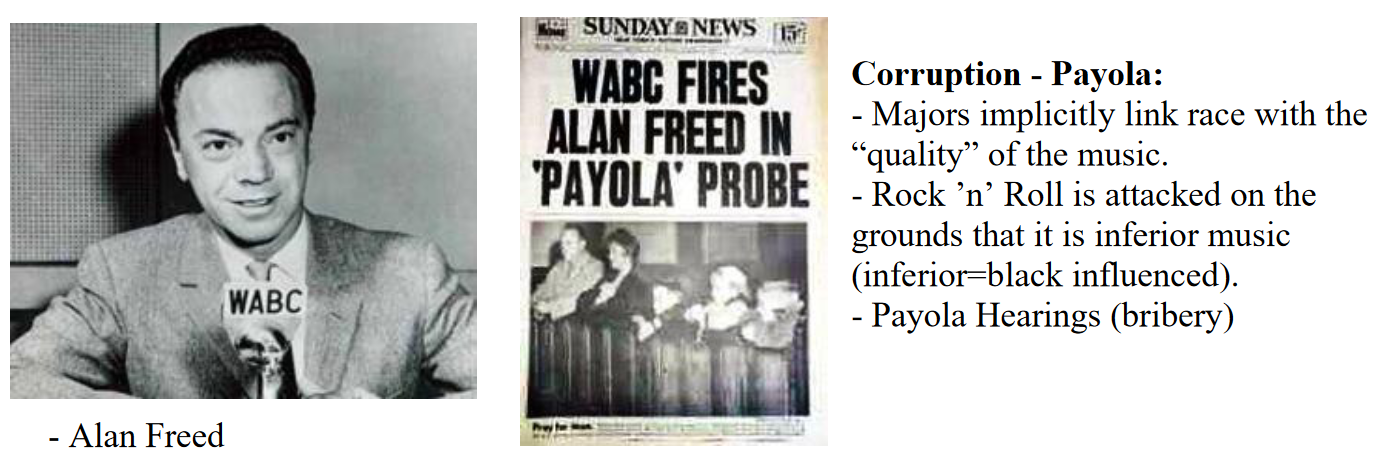

The term “Rock ‘n’ Roll” is most commonly attributed to Alan Freed, a disc jockey on ABC Radio who championed R&B and refused to play sanitized white cover versions of Black hits. While Freed didn’t invent the term, his advocacy helped define and promote the genre’s identity.

Bill Haley and the Comets

One of the earliest performers to bridge these styles was Bill Haley. Originally part of a Western Swing band called the Saddlemen, Haley sensed the shifting tides and began experimenting with R&B-infused arrangements. Hits like “Crazy Man, Crazy” and “Shake, Rattle and Roll” offered early examples of this hybrid style, but it was “Rock Around the Clock” that defined the new genre.

Bill Haley and the Comets: “Rock Around The Clock” (1954, Freedman / Myers)

Though recorded in 1954, the song gained widespread popularity in 1955 after being featured in the film Blackboard Jungle. The movie carried a negative view of Black music, implying that it led youth to delinquency. Ironically, this portrayal only fueled its appeal among rebellious teenagers.

Musically, the track adhered to a 12-bar blues structure and, though performed by a white band, introduced distorted guitar tones and a gritty energy that resonated with youthful audiences. However, Haley, already in his 30s, lacked the youthful charisma that teenagers craved. A new generation of artists was about to take the stage.

Sam Phillips and the Sun Records Legacy

At the heart of this transformation was Sam Phillips, founder of Sun Records. Phillips had a keen ear for innovation and a legendary eye for talent. According to his assistant Marion Keisker, Phillips once remarked:

“If I could find a white man with the singing voice of a Black man, I could make millions.”

This dream materialized when he discovered Elvis Presley.

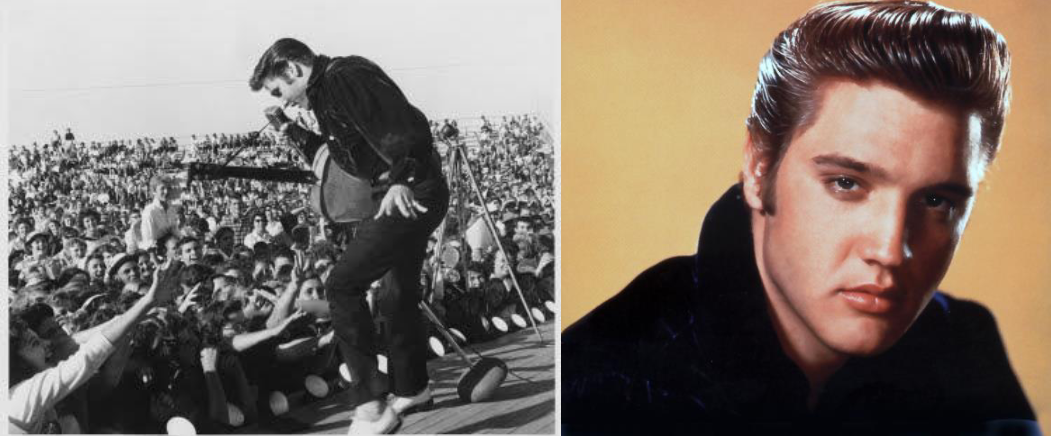

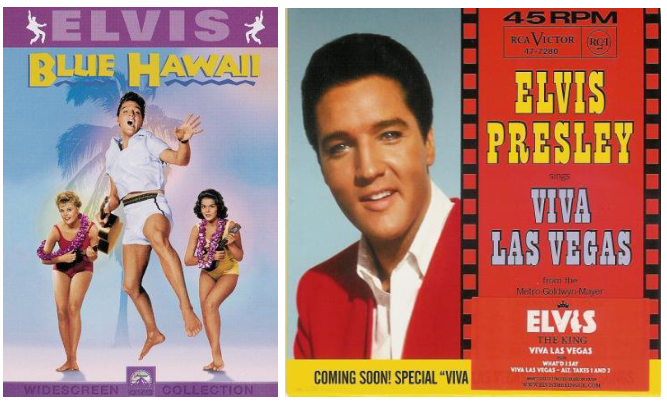

Elvis Presley (1935–1977)

Born in Tupelo, Mississippi, and raised near Memphis, Elvis grew up listening to both R&B and Country. At Sun Records, he initially recorded C&W tracks with guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black—notably without a drummer, in line with country traditions.

Elvis Presley: “That’s Alright Mama”

The turning point came when, during a break, Elvis began playing “That’s Alright Mama,” an R&B hit originally by Arthur Crudup (1946). Dewey Phillips played Elvis’s version on the radio, and the response was overwhelming. To complete the single, they added a revamped version of Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky.”

Elvis Presley: “Blue Moon of Kentucky” (1954)

In Elvis’s hands, Monroe’s waltz-like 3/4 song was transformed into an upbeat 4/4 pop structure. This rhythmic shift, along with energetic vocals and slap bass rhythms, fused C&W with R&B, creating an early Rockabilly style—the precursor to mainstream Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Elvis recorded 12 singles at Sun Records, all covers of songs he loved. Though he didn’t write music, his performance style brought something wholly new. Known as “The Hillbilly Cat,” he became a regional star.

In 1956, Colonel Tom Parker took over as his manager, signing Elvis to RCA and securing national TV appearances. With the addition of drummer D.J. Fontana, Elvis’s sound became more mainstream.

Elvis rocketed to superstardom with hits like “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Hound Dog,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” and “Love Me Tender.” These songs dominated Pop, Country, and R&B charts alike.

His televised performances stirred controversy. One notable example was his rendition of “Hound Dog” on the Milton Berle Show, which included suggestive movements and Black-inspired performance elements, leading to public backlash. In response, his next appearance on The Steve Allen Show was deliberately toned down.

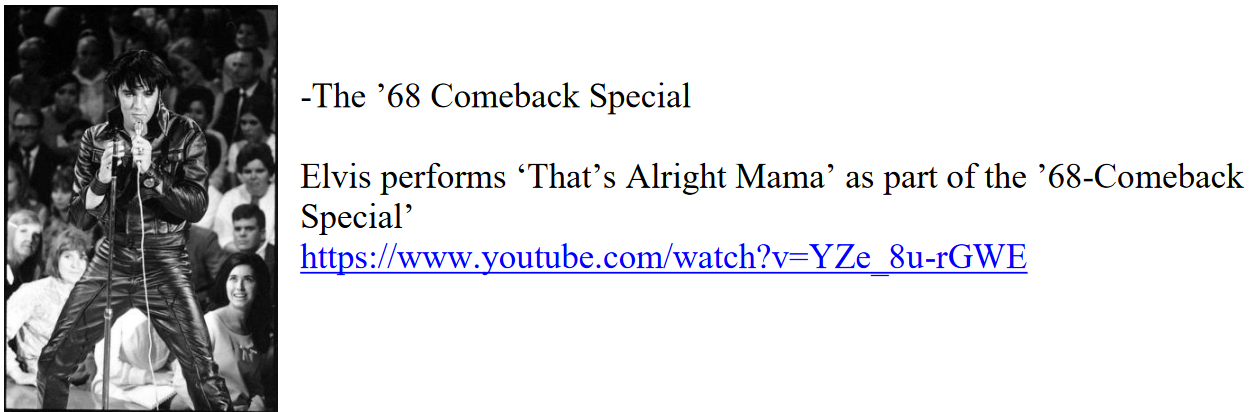

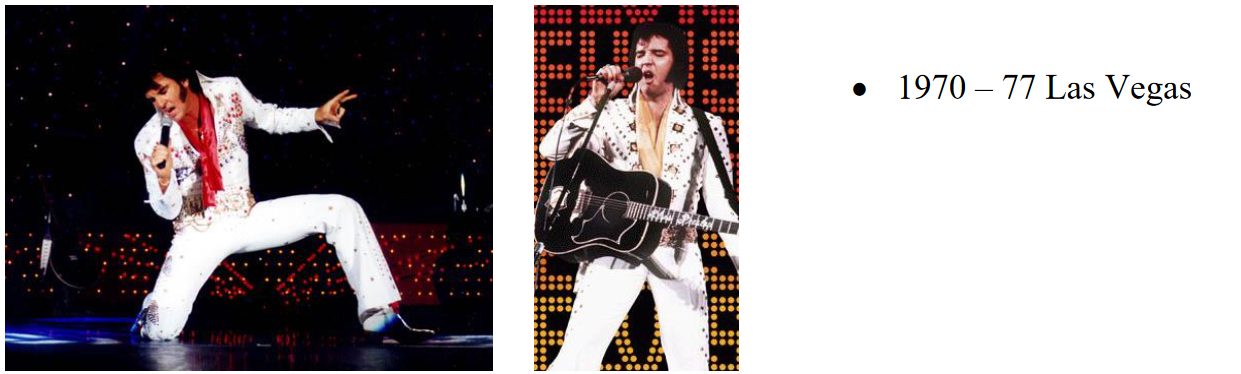

After military service, Parker shifted Elvis’s focus to film and TV appearances. Despite commercial success, this period is often seen as artistically disappointing. Yet, in 1968, Elvis staged a powerful return with his “Comeback Special,” revisiting his rock roots in a leather suit and raw, joyful performance.

He continued performing, especially in Las Vegas, until his untimely death in 1977 at age 42. Despite never writing songs, Elvis is remembered as “The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll” for his cultural impact and role in popularizing the genre.

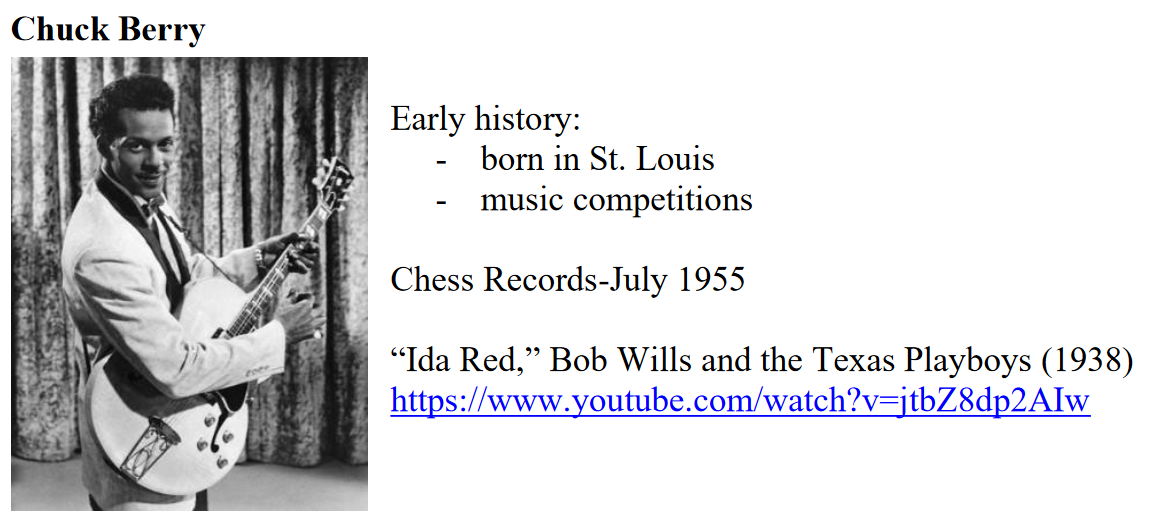

Chuck Berry: The Architect of Rock ‘n’ Roll

While Elvis embodied charisma, Chuck Berry provided Rock ‘n’ Roll with its musical and lyrical blueprint. Born in St. Louis, Berry dreamed of wealth and saw music as his ticket—but he knew he needed to appeal to white audiences to succeed.

Berry self-consciously crafted a sound that incorporated country guitar tones, bright timbres, and clear diction. This allowed him to stand out in R&B contests, winning fans across racial lines. He signed with Chess Records in 1955.

His breakout hit, “Maybellene,” was inspired by the country tune “Ida Red.” At the label’s suggestion, Berry rewrote the lyrics to center around car culture—a topic relatable to teenagers.

Chuck Berry: “Maybellene” (1955)

Lyrically, Berry targeted teenage themes:

- Cars as symbols of freedom

- Romantic encounters from a male perspective

- School avoidance

- Celebration of Rock ‘n’ Roll itself

These became staples of the genre.

The Rise and Fall of Rock’s First Generation

With Chuck Berry’s influence still echoing through the jukeboxes of America, Rock ‘n’ Roll reached its commercial and creative peak. But just as the genre began to hit its stride, a series of unexpected and often bizarre events brought the era to a sudden halt. As we’ll see, fame is a fickle companion—and sometimes a catastrophic one.

Chuck Berry: “Johnny B. Goode” (1958)

Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” captures the full essence of Rock ‘n’ Roll. It’s text-heavy, story-driven, and loaded with clever musical choices:

White Elements:

- Narrative storytelling—white audiences love a good yarn

- Clear enunciation—no mumbling allowed

- Country-inspired bright guitar tones

Black Elements:

- Classic 12-bar blues chord structure

- The added sixth—a boogie-woogie flourish that says, “Let’s dance!”

- Expressive guitar solos with emphasis on timbre, articulation, and rhythm

Chuck Berry wasn’t just a guitarist—he was a strategist. He understood his audience and tailored his performance accordingly:

“All in all, it was my intention to hold both Black and white clientele by voicing the different kinds of songs in their customary tongues.”

Berry may not have been the most commercially successful, but his fingerprints are all over the music that followed. Unlike Elvis, he wrote his own material, giving future rockers a creative blueprint.

The End of the Golden Age (1954–1959)

In just five years, Rock ‘n’ Roll transformed the music industry:

- Revenue tripled from $200M to $600M

- Independent labels surged from 21% to 66% market share

- 42% of the 1959 Pop Top 10 were Rock ‘n’ Roll tracks

But success breeds enemies.

Payola Panic

Major labels, unhappy with losing market share to scrappy independents, cried foul—specifically, “payola,” the practice of bribing radio DJs to play certain records. While this had existed for decades, it was suddenly framed as a Rock ‘n’ Roll problem.

Alan Freed, who had popularized the term “Rock ‘n’ Roll,” became the scapegoat. He was fired and later passed away in disgrace.

Behind the moral panic was a familiar foe: racism. Critics portrayed Rock ‘n’ Roll as dangerous, degenerate, and worst of all, Black-influenced. The genre’s popularity among white teens only deepened the panic.

The Great Extinction

By 1959, it was as if someone had pulled the plug on Rock ‘n’ Roll’s first wave:

Elvis Presley was drafted into the army and returned with a cleaner, duller image.

Chuck Berry was jailed under the Mann Act for transporting a minor across state lines. His career never fully recovered.

Jerry Lee Lewis shocked the public by marrying his 13-year-old cousin. Even for rock stars, there are limits.

Little Richard found religion after a scare on an airplane and abandoned music for the pulpit.

Buddy Holly, along with Ritchie Valens and The Big Bopper, died in a tragic plane crash—a moment later immortalized as “The Day the Music Died.”

The genre wasn’t dead, but it was definitely in a coma. What followed was a strange period known as…

The “In-Between” Years (1959–1963)

With the original stars of Rock ‘n’ Roll either gone or diminished, the early 1960s marked a transitional phase in pop music history. Major labels took back control—but now, they had learned an important lesson: Rock ‘n’ Roll wasn’t just a fad.

Instead of resisting it, they co-opted it.

Dance Crazes

One strategy was the Dance Craze: music that maintained Rock ‘n’ Roll energy but came with choreographed moves—making it more parent-approved.

Example: Chubby Checker – “The Twist”

- Infectious beat rooted in the 12-bar blues

- Clean lyrics with simple dance instructions

- Hugely popular with both teens and their parents

Example: Little Eva – “The Locomotion” (1962)

- Written by Goffin and King

- Retains the sound of Rock ‘n’ Roll—strong drums and saxophone

- Lyrics instruct the listener how to dance

- Eva earned just $52/week; the label kept the profits

TV programs featured white teens dancing to these songs to make them seem wholesome.

Teenage Idols

At the same time, labels created “Teenage Idols”—clean-cut, handsome young men marketed as safe heartthrobs for teenage girls (and their mothers).

Example: Bobby Vinton – “Blue Velvet” (1963)

- A remake of a 1951 Tony Bennett hit

- Features lush orchestration and smooth vocals

- Echoes TPA’s romantic idealism

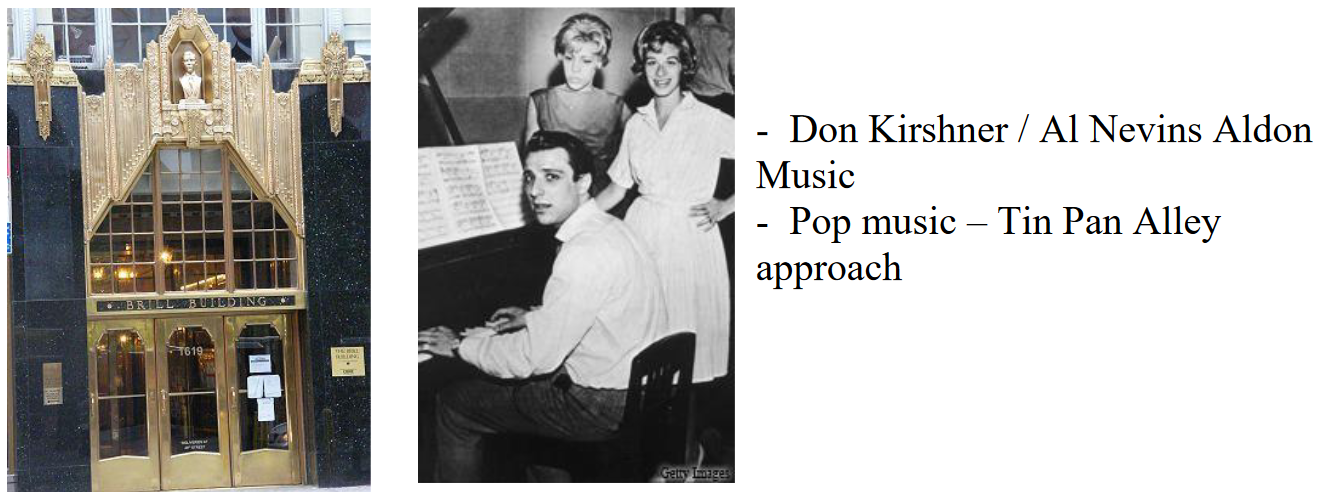

The Brill Building and the Return of Song Factories

Songwriting during this period was largely concentrated in The Brill Building, a New York office complex that housed teams of professional composers.

- Aldon Music (founded by Al Nevins and Don Kirshner)

- Songwriting duos (e.g., Goffin and King) wrote hits in small rooms, quickly passed to performers

- Emphasized division of labor—echoing Tin Pan Alley

Recording Technology Revolution

While the music grew tamer, technology was quietly transforming everything.

The Magnetophon

Brought from Nazi Germany after WWII, the Magnetophon revolutionized audio recording:

- High fidelity

- Easier to store

- Enabled editing

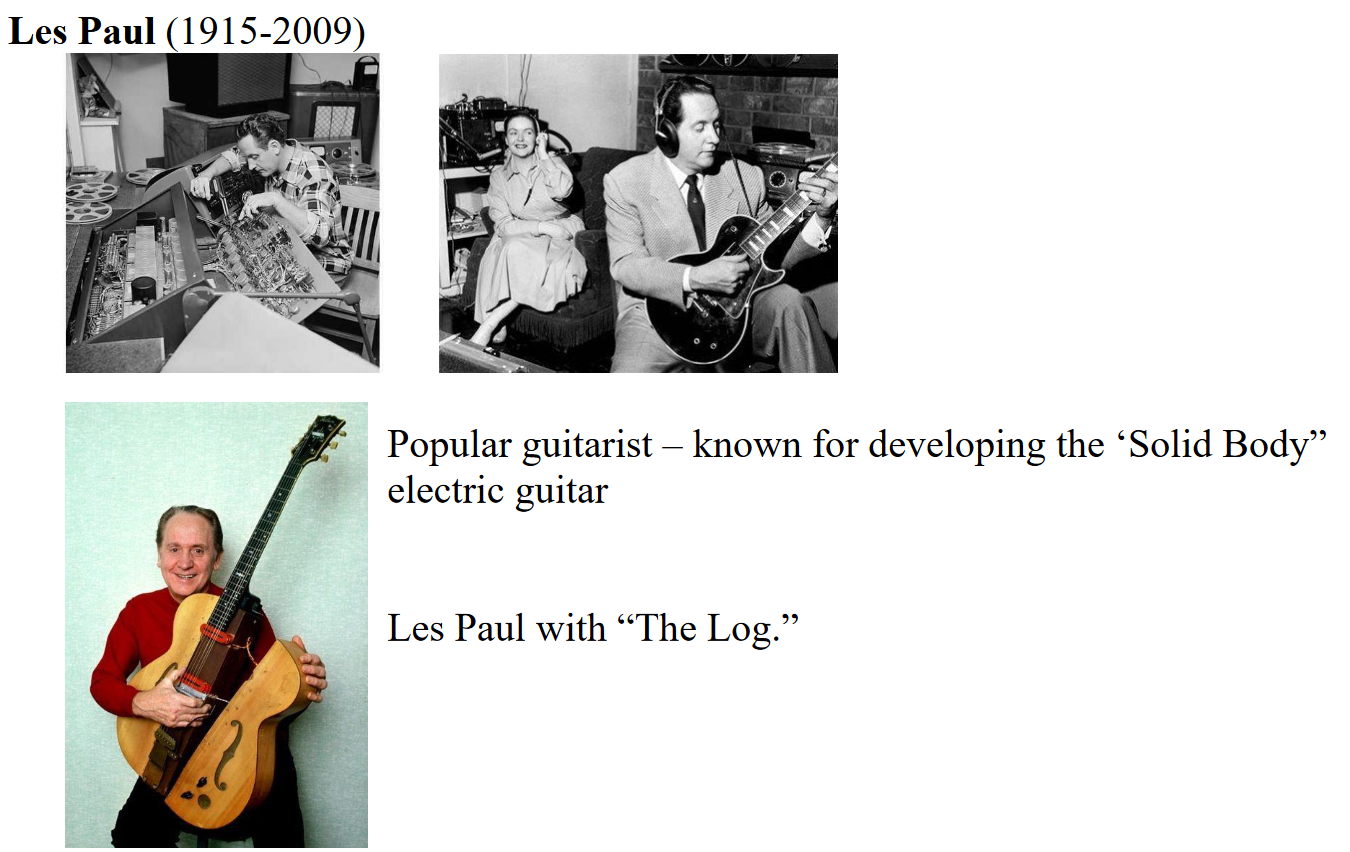

Les Paul and Multitrack Recording

Les Paul—a guitarist and inventor—developed:

- The solid-body electric guitar (e.g., the Gibson Les Paul)

- Multitrack recording: layering different performances over time

Example: “Sitting On Top Of The World” (Les Paul & Mary Ford, 1953)

- Showcases speed manipulation and audio layering

- Not a real-time performance, but a constructed artifact

- This marks the shift from reproduction (capturing a performance) to production (crafting a song from raw materials)

Producers were no longer passive engineers—they became creative forces.

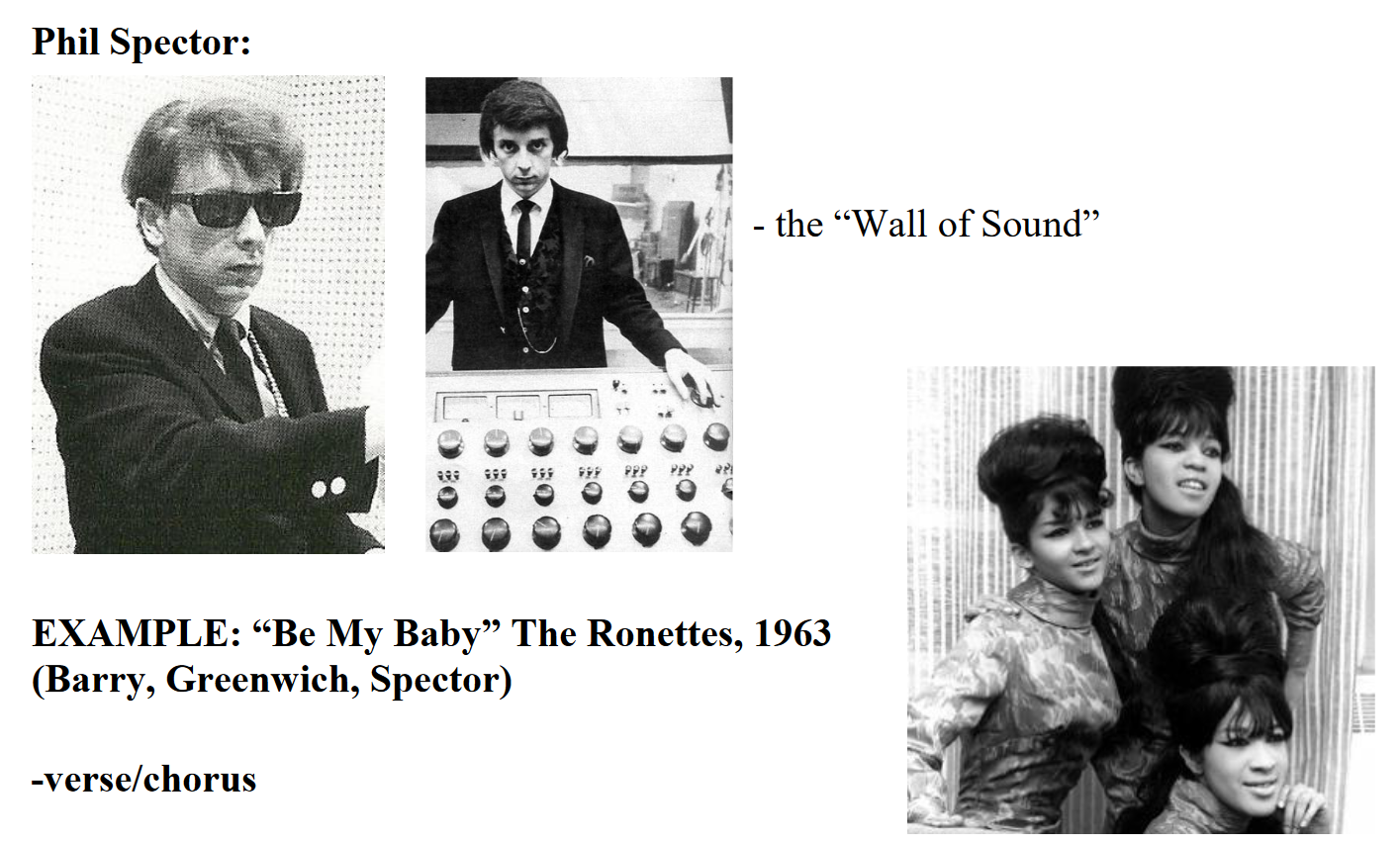

Phil Spector and the “Wall of Sound”

Phil Spector took multitrack recording further:

- Layered multiple instruments to create a dense, echoing “Wall of Sound”

- Called his songs “little symphonies for kids”

Example: The Ronettes – “Be My Baby” (1963)

- Verse/chorus form replaces AABA

- Rich, immersive texture

- Built for teenage audiences—and high emotional impact

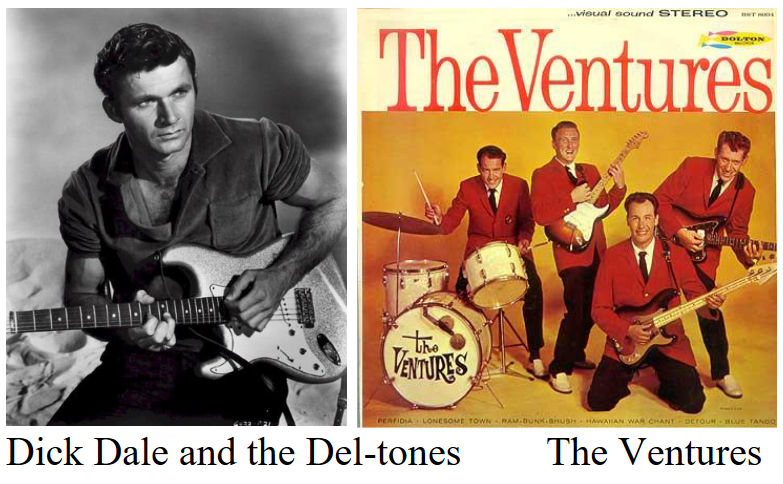

Surf Music and the Survival of Rock ‘n’ Roll

While the mainstream embraced teenage idols and dance crazes, a more authentic form of Rock ‘n’ Roll survived on the West Coast.

- Replaced double bass with electric bass

- Bands like The Ventures played their own instruments and wrote their own music

- Focus on electric guitar, often instrumental

Example: “Misirlou” – Dick Dale (1962)

- Rapid, staccato picking

- Middle Eastern influences

- Later re-popularized by Pulp Fiction

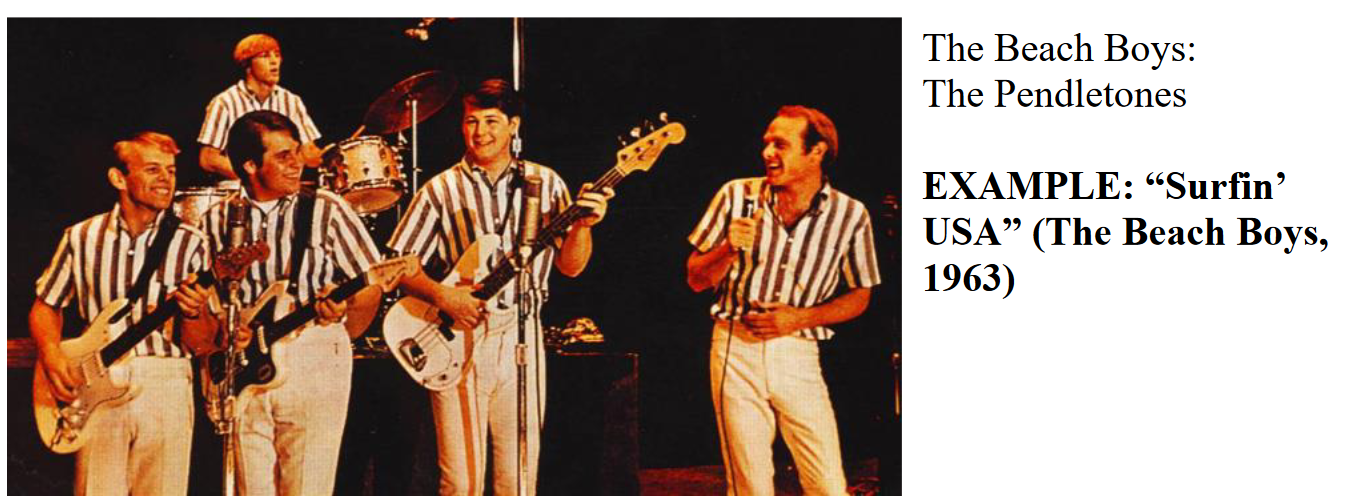

The Beach Boys

The definitive Surf Rock band:

- Originally called The Pendletones

- Clean harmonies, upbeat energy

- Inspired heavily by Chuck Berry

Example: “Surfin’ USA” (1963)

- Based on Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen”

- Berry was later credited as co-writer

- Marked the Rockabilly-to-Surf evolution

Brian Wilson, the band’s creative heart, would later lead them toward more ambitious musical territory. But for now, Surf Music kept Rock ‘n’ Roll’s flame alive during the quiet years before The Beatles changed everything.

Here is a polished and seamlessly connected version of Class 7 and Class 8, consistent with the tone, clarity, and flow of your earlier sections. All original content and images are retained, and transitions are added where necessary to maintain narrative continuity.

The Beatles and the British Invasion

As the 1960s progressed, the cultural epicenter of pop music began to shift. While the United States had birthed Rock ‘n’ Roll, its next great evolution would be sparked across the Atlantic. In post-war Britain, a new generation of musicians was coming of age under difficult conditions—and finding inspiration in the very American music that many U.S. record companies had dismissed.

Post-War Britain: Fertile Ground for Youth Creativity

In the aftermath of WWII, the U.S. enjoyed a period of economic prosperity—but the same could not be said for the United Kingdom. Post-war Britain faced economic stagnation, austerity, and a lack of opportunity, particularly for young people. With jobs scarce and optimism in short supply, British youth developed a rebellious, self-reliant spirit. This gave rise to a “Do It Yourself” (DIY) ethos that extended into fashion, art, and especially music.

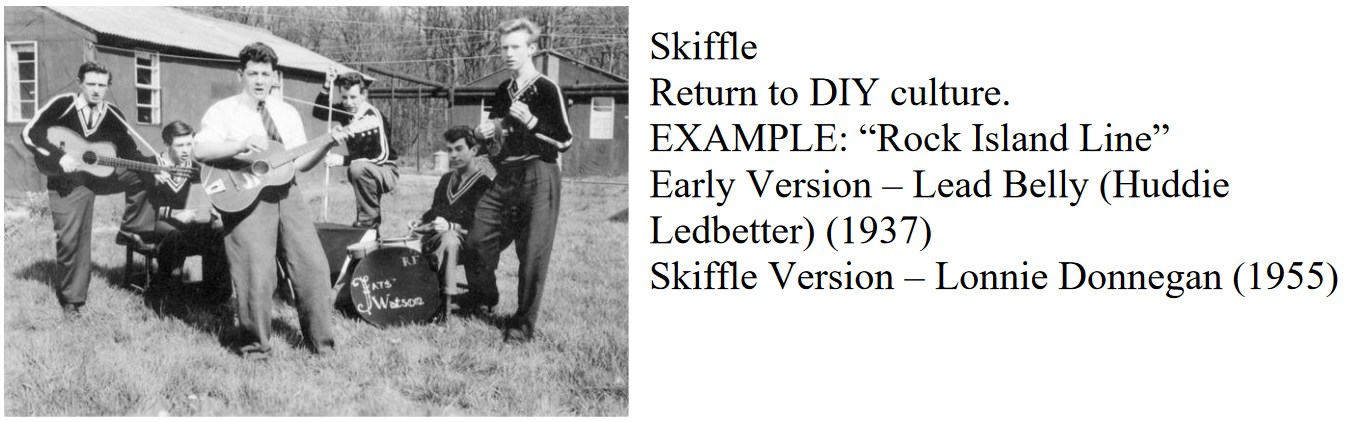

Skiffle: The British DIY Sound

Inexpensive, raw, and energetic, Skiffle became the first expression of post-war British youth music. Drawing influence from American folk, blues, and early Rock ‘n’ Roll, skiffle bands used improvised instruments like washboards and tea-chest basses alongside guitars.

Example: Lonnie Donegan – “Rock Island Line” (1955)

Originally recorded by American folk and blues artist Lead Belly in 1937, Donegan’s fast, spirited rendition gave skiffle its first major hit and helped ignite a musical movement across Britain. This fusion of American roots with British sensibility laid the groundwork for the next musical revolution.

The Quarrymen and the Formation of The Beatles

One of the many skiffle bands inspired by Donegan’s success was The Quarrymen, founded in Liverpool—a bustling port city with easy access to imported American records.

- In July 1957, at a church picnic, John Lennon met Paul McCartney, and John invited him to join the group.

- They were especially impressed that they both wrote original songs, and soon began composing music together nearly every day.

Over the next few years, the band evolved:

- George Harrison joined in March 1958 as lead guitarist.

- Pete Best became their drummer in Summer 1960.

- In August 1960, the group adopted the name The Beatles.

By this time, they were already gaining popularity in Liverpool and in Hamburg, Germany, where U.S. troops stationed during the Cold War demanded live entertainment. Because Hamburg was too far from the U.S., British bands like The Beatles were hired to perform, sharpening their skills through grueling all-night shows.

Back home, the band was building a loyal following through regular appearances at The Cavern Club in Liverpool. Their early image was rough and rebellious, styled after American biker gangs—complete with leather jackets and bad attitudes.

Brian Epstein: Manager and Image Architect

In December 1961, wealthy businessman Brian Epstein attended a Cavern Club performance and offered to manage the band.

Epstein quickly recognized their potential and suggested a major image overhaul—polished suits, uniform haircuts, and respectful manners. The transformation was dramatic, helping to broaden their appeal.

Despite the fresh look, Epstein initially struggled to secure a recording contract. In a now-infamous rejection letter, Dick Rowe of Decca Records declared that “guitar groups are on their way out”—a comment that would haunt the label.

George Martin and the Breakthrough

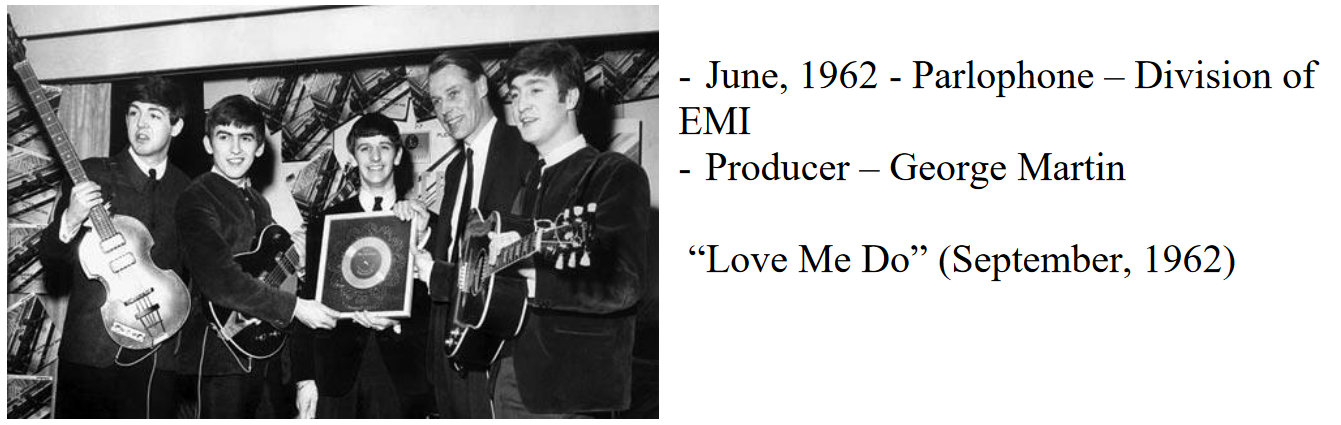

After months of rejections, Epstein finally secured a contract with Parlophone, a division of EMI, in June 1962. Their assigned producer, George Martin, brought not only technical expertise but also a deep knowledge of classical music. Upon meeting the group, Martin requested the dismissal of drummer Pete Best, a suggestion welcomed by Lennon. Ringo Starr was brought in as the new drummer.

Their first single, “Love Me Do” (September 1962), became a modest hit. It was their next single that truly launched their career:

The Beatles: “Please Please Me” (January 1963)

- AABA form – a traditional structure used in TPA

- Vocal rhythm shifts between A and B sections for contrast

- Sustained high note links the B section to the final A

- Background details demonstrate increasing self-conscious artistry

By late 1963, The Beatles had become England’s biggest band, culminating in a performance at The Royal Variety Show before the Queen.

The British Invasion Begins: February 1964

With their U.K. dominance secured, Parlophone aimed to break the U.S. market. Epstein insisted they wait until they had a genuine American hit. That moment came with “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, which topped U.S. charts by the end of 1963.

The Beatles landed in America in February 1964, prompting a cultural earthquake.

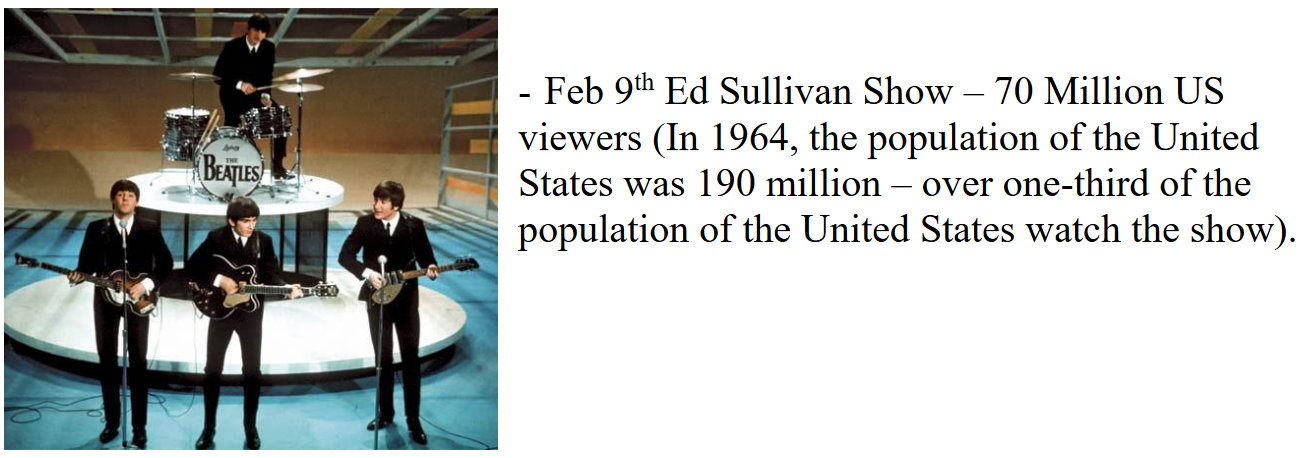

Their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show reached 70 million viewers, electrifying American youth and launching what became known as the British Invasion.

Their arena performance shortly after was a first in music history—the birth of the modern stadium concert. This necessitated innovations in light and sound system design.

Within just two weeks, The Beatles sold 2 million albums and generated $2.5 million in merchandise. They redefined music marketing and helped invent modern fan culture.

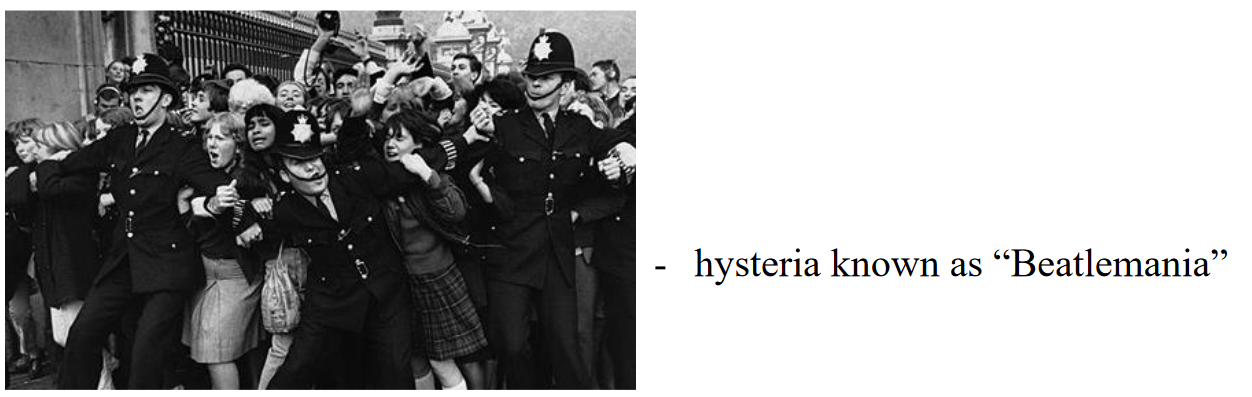

The phenomenon of Beatlemania—hysterical fans, shrieking crowds, and obsessive devotion—was so intense that some doctors classified it as a psychological event.

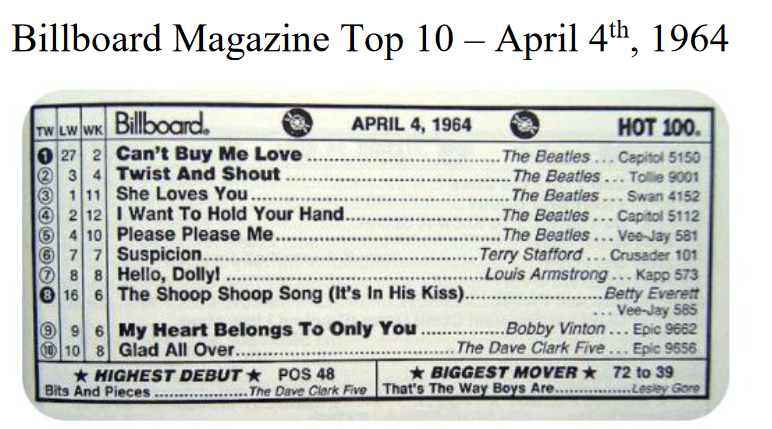

In April 1964, The Beatles occupied the Top 5 spots on the Billboard Hot 100—an unprecedented feat.

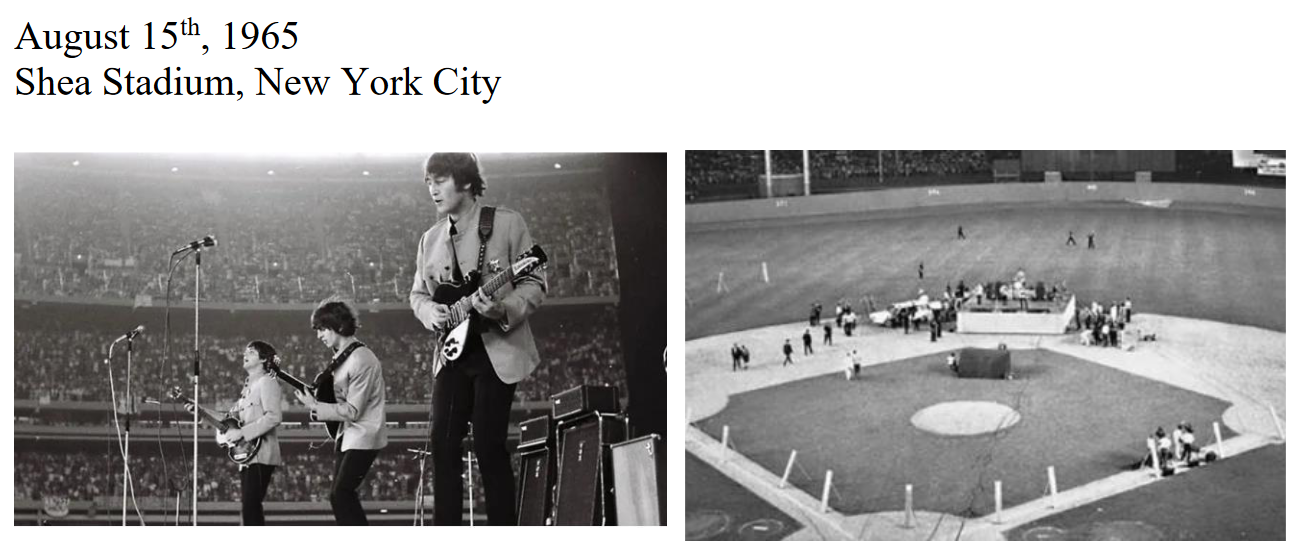

The Shea Stadium Concert and Mass Live Entertainment

Their 1965 Shea Stadium concert drew over 65,000 fans, marking a turning point in the scale of live music events. As post-war America invested in stadiums and arenas for sports teams, The Beatles revealed how music could fill those venues on off-nights, shaping the future of touring.

Merseybeat and Musical Influence

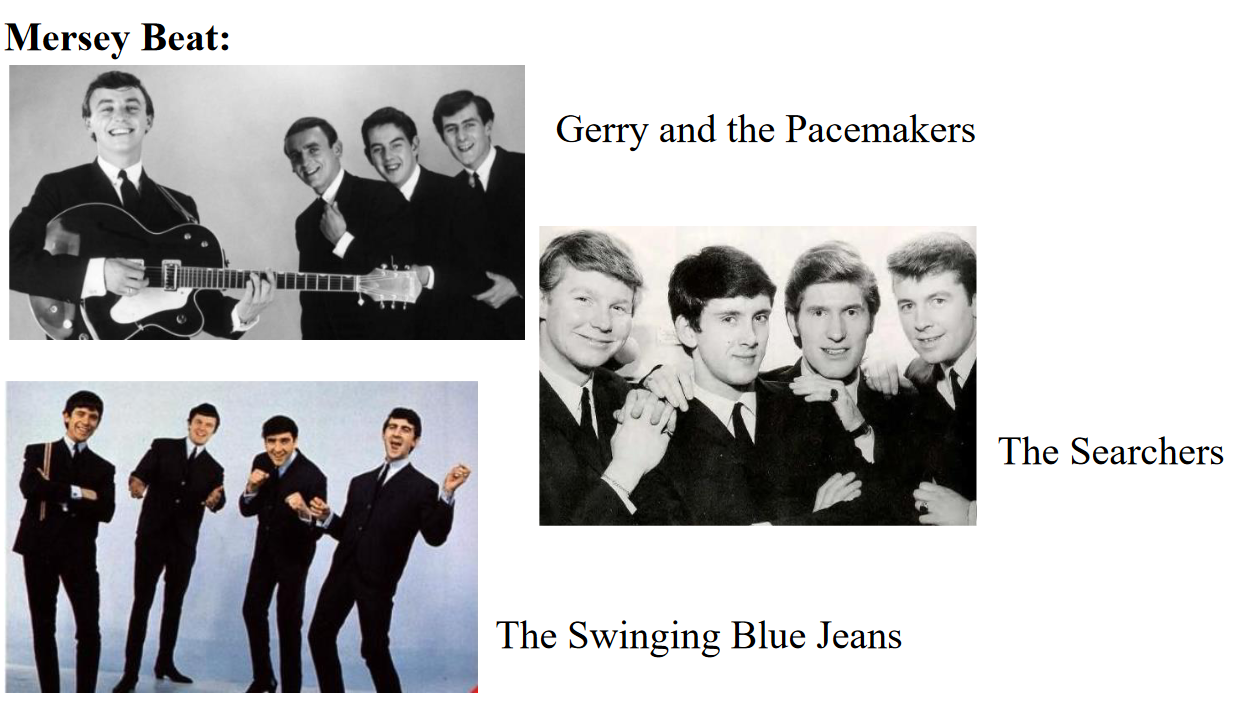

Their early style, dubbed Merseybeat, became a template for other British acts like Gerry and the Pacemakers, The Searchers, and The Swinging Blue Jeans.

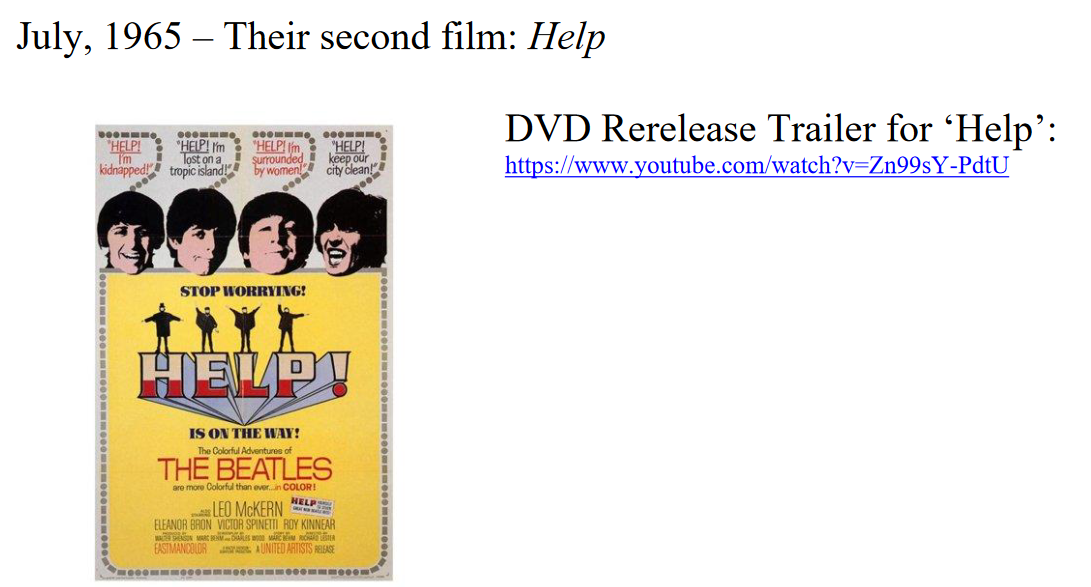

The Beatles and Film

Like Elvis before them, The Beatles also made films—but always played themselves, not fictional characters. They composed original songs for each film.

Help! (July 1965) and the Song “Yesterday”

- Primarily written by Paul McCartney

- Uses AABA form

- Features a string quartet, suggested by producer George Martin

- McCartney performs nearly the entire track solo

“Yesterday” marks the band’s turn toward more sophisticated harmonies, lyrics, and musical arrangements, signaling their artistic evolution.

As the mid-1960s progressed, The Beatles matured artistically, leaving behind their early pop sound in pursuit of deeper expression and innovation.

- Help! (August 1965) still carried the upbeat feel of their early hits.

- Rubber Soul (December 1965) introduced musical experimentation and unconventional album art.

- Revolver (August 1966) pushed boundaries even further.

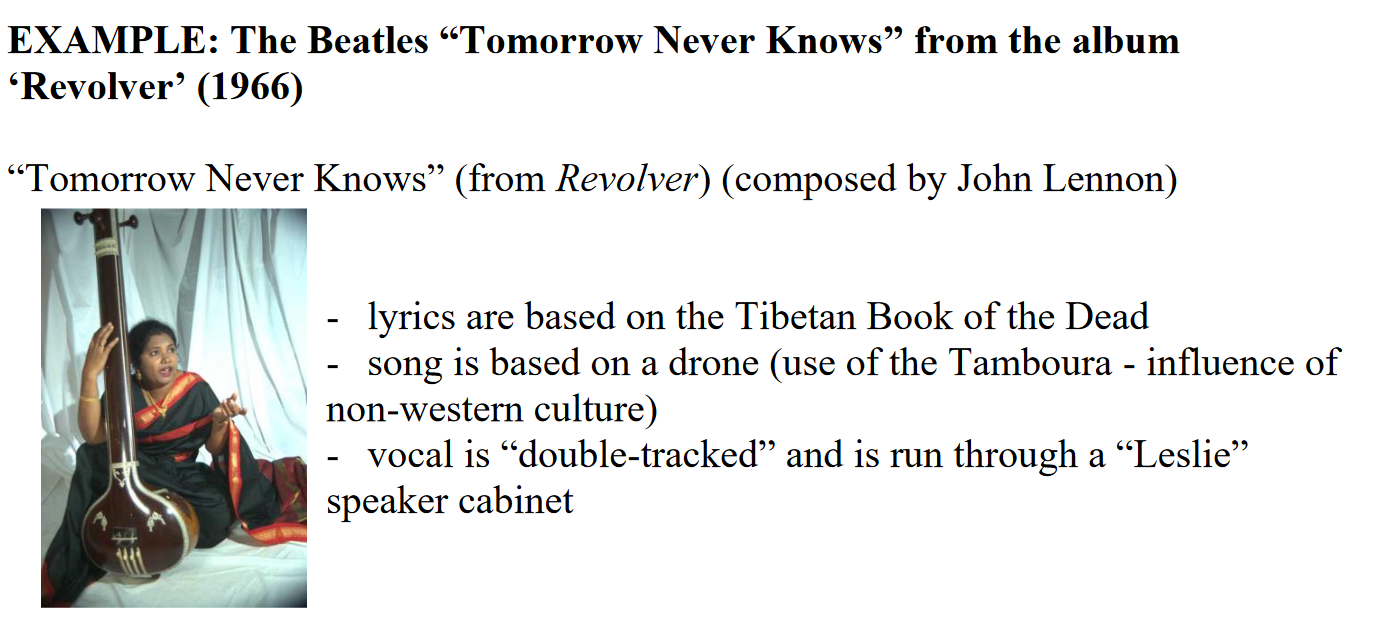

“Tomorrow Never Knows” – The Beatles (1966)

This landmark track from Revolver showcases their growing interest in non-Western philosophy and cutting-edge studio technology.

- Lyrics by John Lennon, inspired by The Tibetan Book of the Dead

Influenced by classical Indian music

- Uses drone, performed on a tamboura

- Double-tracked vocals create a richer sound

- Lennon’s voice runs through a Leslie speaker, creating a swirling, psychedelic effect

- Incorporates tape loops and backward guitar solos

- Avant-garde production renders the song impossible to perform live

This track exemplifies how technology and global influences were reshaping The Beatles’ creative process. Touring no longer satisfied them—especially as their performances were often drowned out by screaming fans.

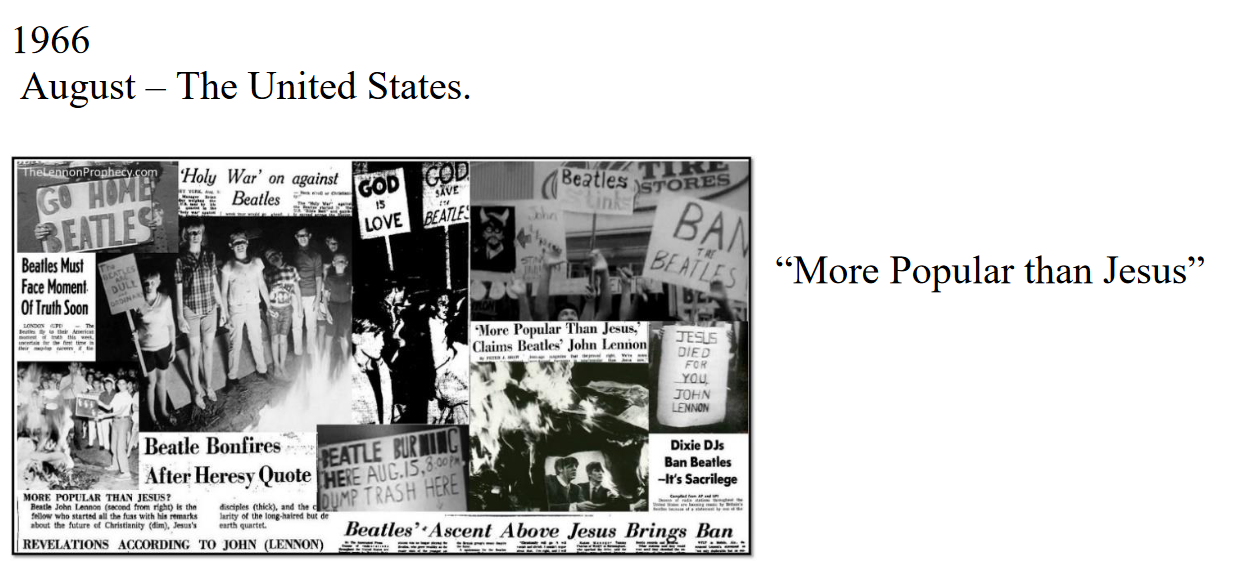

In a 1966 interview, John Lennon remarked that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus,” sparking outrage and protests during their U.S. tour.

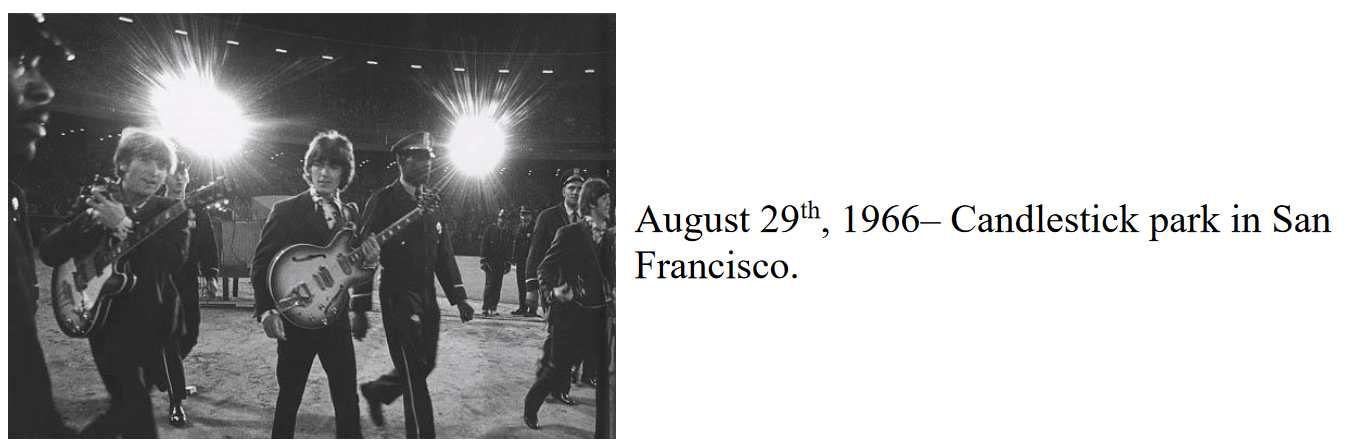

After a final performance in San Francisco, they announced they would stop touring and focus exclusively on studio work.

“Strawberry Fields Forever” (February 1967)

Released alongside a short experimental film, this single marked their full commitment to artistic exploration, firmly rejecting the pursuit of pop chart success.

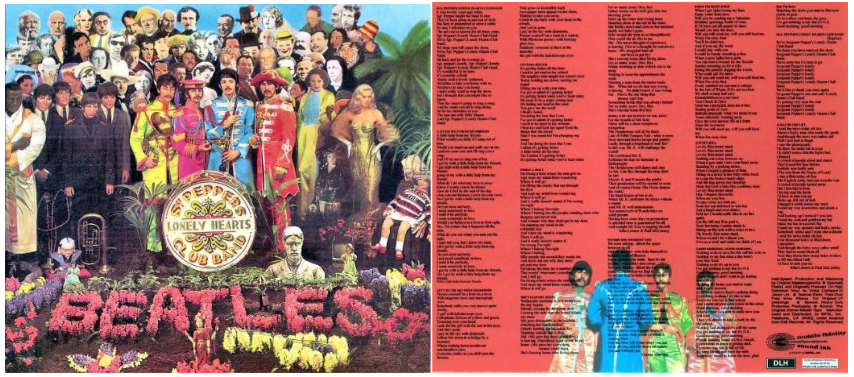

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (June 1967)

This album is widely regarded as one of the most influential in history.

- Cover: Features The Beatles surrounded by famous figures—including younger versions of themselves

- Back Cover: Printed lyrics for every track, a first for a pop album

Though only loosely connected, it is often considered the first major concept album, centered on the idea of a fictional band performing in place of The Beatles.

The “Hippie Aesthetic”

Sgt. Pepper signaled a major shift in popular music, marking the rise of the Hippie Aesthetic:

- Transition from Rock ‘n’ Roll (singles, dancing, entertainers) to Rock (albums, listening, artists)

- Albums viewed as cohesive artistic works

- Artists expected to experiment, evolve, and engage deeply with their craft

Though the term “Hippie Aesthetic” references a short-lived countercultural movement, its values continue to influence music today.

Final Track: “A Day in the Life”

- Lennon and McCartney contribute contrasting sections

- The orchestral transition was created by telling 40 musicians to ascend from the lowest to highest note in 20 seconds

- Avant-garde structure and surreal lyrics pushed the boundaries of what pop music could be

The creative tension between Lennon and McCartney is already evident. Their diverging artistic visions would eventually contribute to the band’s dissolution—especially after Brian Epstein’s death from a drug overdose.

By September 1969, The Beatles had effectively broken up, formally announcing their split in 1970. In less than a decade—from Fall 1962 to 1970—they transformed popular music forever.

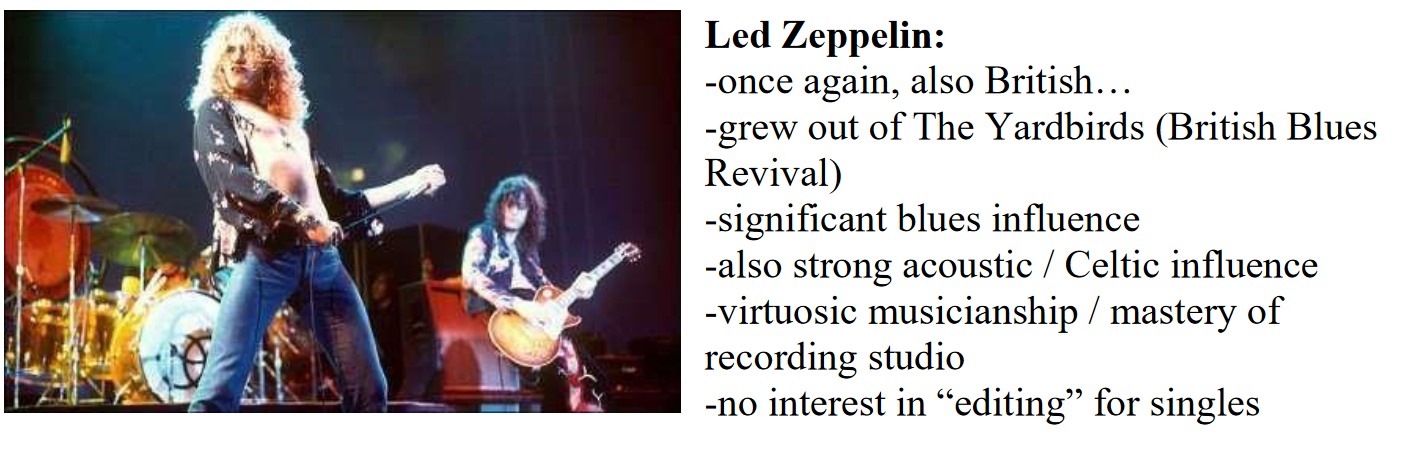

The British Blues Revival

In the post-war years, many British youth—especially in London—became fascinated by American blues music.

- In 1958, the Chess Records Tour brought American bluesmen like Muddy Waters to the U.K. for the first time.

- Ironically, Waters was struggling in the U.S. as Rock ‘n’ Roll overtook R&B in popularity. But in England, teenagers were captivated by his sound.

This transatlantic admiration sparked what became known as the British Blues Revival, which shaped a generation of bands:

- Fleetwood Mac

- Cream

- Eric Clapton

- Led Zeppelin

- The Rolling Stones

These artists revered American blues as both inspiration and foundation. Their covers and adaptations of blues standards introduced Black American music to a broader global audience—often without credit or compensation for the originators.

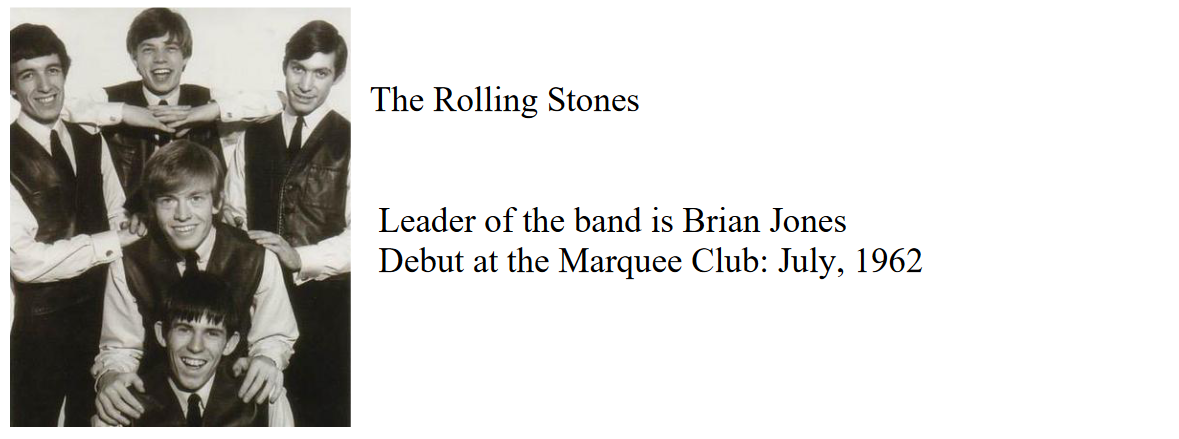

The Rolling Stones

The leader, Brian Jones, had deep knowledge of American blues and assembled the band to honor that tradition.

- Debuted at the Marquee Club in July 1962

- They had no name at the time, but picked one spontaneously from a Muddy Waters record—“Like a Rolling Stone”

Soon after, they gained traction performing at the Crawdaddy Club.

Andrew Loog Oldham

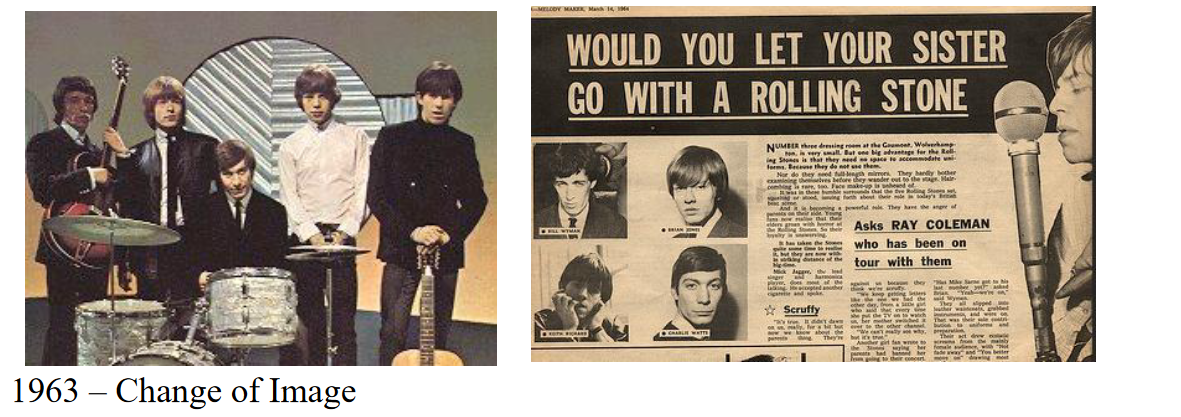

In April 1963, Andrew Loog Oldham and Eric Easton approached the band about management.

- Oldham rebranded the group’s image: wild, messy, sullen, and unpolished—the anti-Beatles

- He coined the phrase: “Would you let your sister go with a Rolling Stone?”

- This made them stand out in a Beatle-dominated market

Interestingly, while their public image was rebellious, most of the members were from middle-class backgrounds. For example, Mick Jagger studied at the London School of Economics.

- Dick Rowe, the Decca executive who had famously rejected The Beatles, later asked them who else to sign—they recommended The Rolling Stones.

Their early recordings (1963–64) were all covers, mostly by:

- Chuck Berry

- Buddy Holly

- Willie Dixon

Jones favored pure blues covers, but others wanted a more balanced repertoire.

“I Wanna Be Your Man” – November 1963 (Lennon/McCartney)

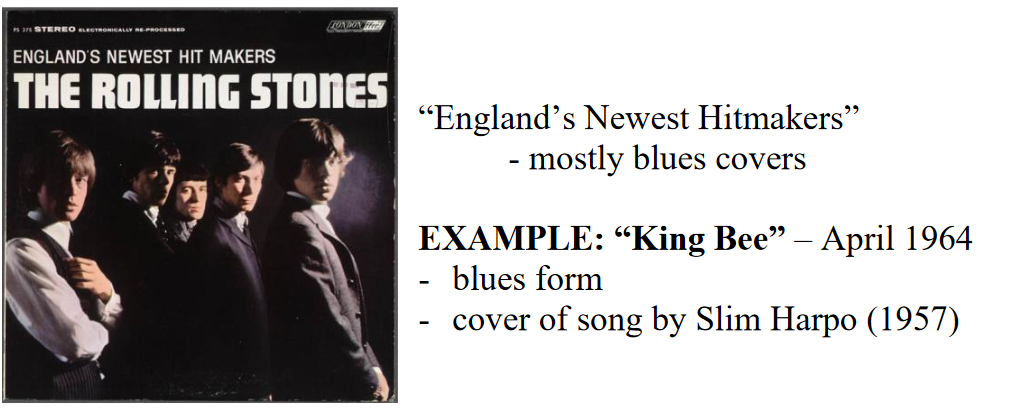

Oldham pushed them to write original material. With no songwriting experience, he invited Lennon and McCartney to the studio, who composed “I Wanna Be Your Man” on the spot for them.

- Included in their debut album: England’s Newest Hitmakers

- Album was still mostly blues covers; Brian Jones remained the dominant figure.

The Rolling Stones: “King Bee” (April 1964)

- Cover of a 1957 song by Slim Harpo

- Classic 12-bar blues

- The band tried to imitate American Black vocal styles and accents

This performance—by white, working-class Londoners—demonstrated how British musicians were earnestly studying and emulating African American blues.

Birth of the Jagger/Richards Songwriting Team

Lennon and McCartney advised them: “Keep a tape recorder by your bed for ideas.”

One night, Keith Richards awoke to find he’d recorded 15 seconds of a riff—and 45 minutes of snoring.

That short riff became:

“(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” – February 1965 (Jagger/Richards)

- Lyrics critique American consumer culture

- Keith Richards wanted the riff played by a horn section

- Instead, they used a distorted guitar as a placeholder—but liked the sound so much they kept it

This became the Rolling Stones’ first U.S. #1 pop hit, establishing them as a global force.

The Beatles vs. The Rolling Stones

| The Beatles | The Rolling Stones |

|---|---|

| Working-class origins | Middle-class origins |

| Clean-cut, suited image | Rebellious, messy image |

| Popular with the middle class | Popular with the working class |

| Focused on the product (ideal version) | Focused on the process (improvisation) |

| Songs rarely varied in performance | Songs changed with each performance |

These differences reflect racialized musical traditions:

- Product-focus = white musical culture (e.g. TPA)

- Process-focus = black musical culture (e.g. gospel, blues)

Rock and Roll fused these worlds, creating hybrid styles that transcended racial and cultural divides.

Despite starting in 1962, The Rolling Stones are still touring today.

But Brian Jones, the band’s founder, became increasingly isolated:

- Focused only on R&B covers

- Disengaged from rehearsals

- Struggled with drug problems

- Was forced out of the band in 1969

Six weeks later, he was found dead in his swimming pool at the age of 27—a tragic precursor to the “27 Club.”

Soul and Funk: Music as Politics and Identity

Music is inherently political: who gets power, who doesn’t, who gets attention, who’s ignored. The development of Soul and Funk is intimately linked to The Civil Rights movement and the evolution of African American identity.

Consider Star Trek: while the Captain was a white American, other crew members included a Russian, a Japanese officer, and a black woman. Martin Luther King commented that this black woman was significant for his daughters to see on television—representation matters.

As the Civil Rights movement progressed, Black Americans began viewing R&B as the music of the past—tied to the rural South and slavery. They needed something new and optimistic: Soul.

Soul: A Musical Revolution

Soul emerged as a powerful fusion of three key elements:

- Vocal style from Gospel (both traditional Gospel and Ray Charles’ innovations)

- Rhythm beat of R&B, but sped up and targeted at dancing and celebration

- Arrangements and lyric styles from TPA (Tin Pan Alley):

- Lyrics focused on idealized romance rather than direct, sexual content

- Arrangements becoming increasingly sophisticated

Two major centers emerged for Soul music, each with distinctly different philosophies and sounds.

Motown: The Hit Factory - Detroit

Notice it says “Hitsville, USA”—not Motown. This wasn’t accidental.

Founded by Berry Gordy in 1959, Motown represented a revolutionary approach to music production. Gordy brought a unique background: professional boxer, Ford assembly line worker, record store owner, and one of the first successful black entrepreneurs who also wrote songs.

Inspired by the Ford assembly line, Gordy created a music assembly line. Beyond division of labor, he wanted everything under one roof. His goal: make music targeted at Black Americans while maintaining appeal to middle-class white audiences.

Key Personnel:

- Holland/Dozier/Holland, Smokey Robinson: Songwriters

- Smokey Robinson: best producer for early Motown

- H-D-H: Top producers from 1964-1967, left due to royalty disputes

- Valerie Ashford and Nick Simpson: produced for Marvin Gaye in late 1960s

- Norman Whitfield: produced for The Temptations in 1970s

- Maxine Powell: Finishing School instructor (女子礼仪学校)—teaching artists etiquette to perform anywhere, even the White House

- Cholly Atkins: Choreographer (编舞者)

- The Funk Brothers: House band backing all artists

This assembly line produced consistent product: same songwriters, same dance moves, same backing band for every artist—similar to Brill Building practices.

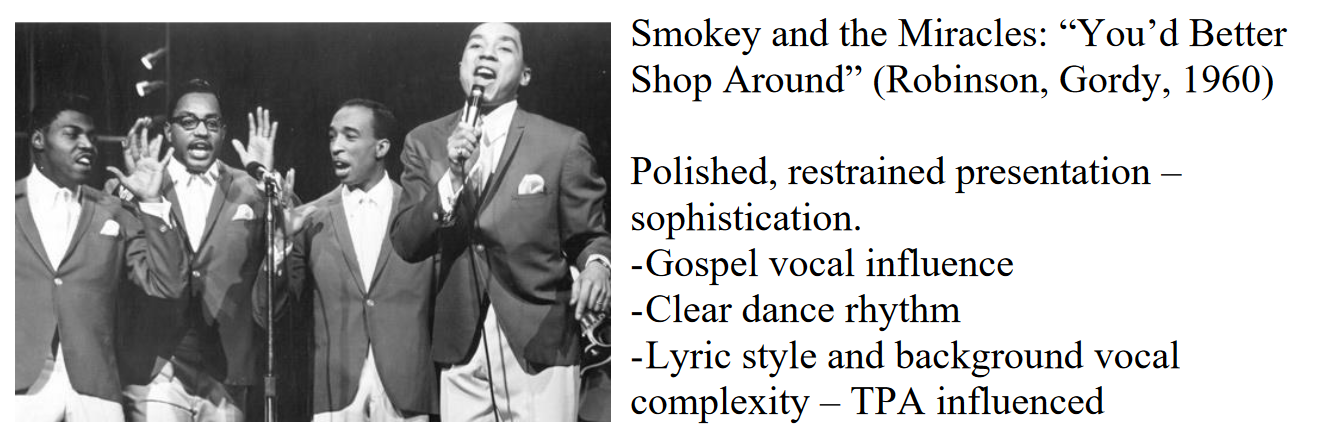

Example: Smokey and the Miracles: “You’d Better Shop Around” (Robinson, Gordy, 1960)

- Polished, restrained, sophisticated presentation like TPA—both vocally and choreographically, trying to appeal to middle-class whites

- Gospel vocal influence evident

- Clear dance rhythm

- Sophisticated lyrics and background vocals

A significant shift occurred: this was black music but no longer focused on bands. Performances were usually lip-synced, showcasing only vocalists with band members invisible.

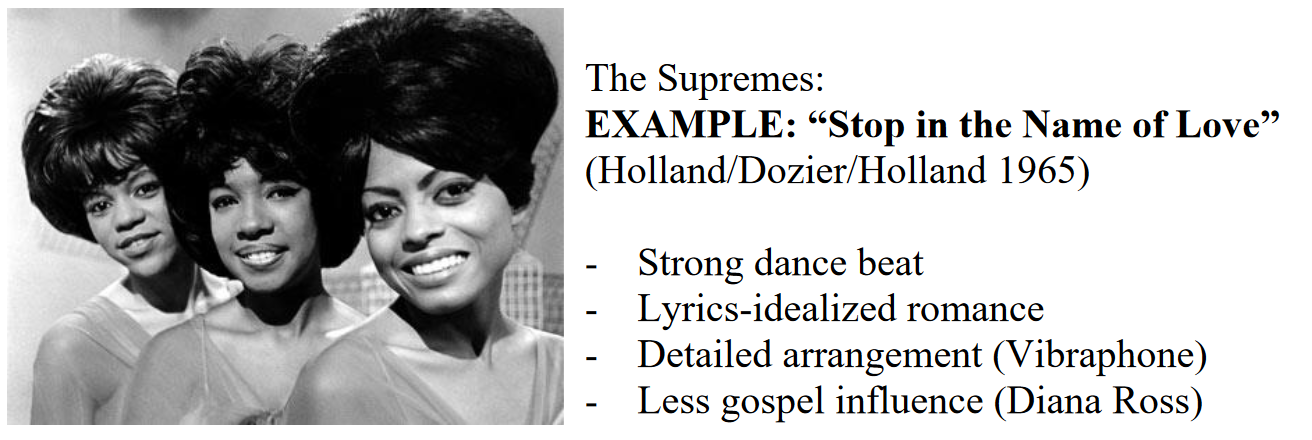

Another Example: The Supremes: “Stop in the Name of Love” (Holland/Dozier/Holland 1965)

- Strong dance beat

- Idealized romance lyrics

- Detailed arrangements featuring vibraphone

- Less gospel influence, more restrained (from Diana Ross, the lead singer)

Contrary to rumors, Diana Ross wasn’t lead singer because she was Gordy’s girlfriend. Berry Gordy was a ruthless businessman focused entirely on making hit songs—hence “Hitsville USA.” Motown music always featured R&B dancing beats and sophisticated arrangements, but not always Gospel vocals.

Sound and Production at Hitsville

- Dancing beats with idealized romance lyrics

- Sophisticated arrangement focus

- Clear vocal timbre and sound clarity

- Multitrack recording usage

- Precise, accurate recording

- “Quality Control”: weekly listening sessions of top 10 pop hits to adjust their music accordingly

“Hitsville USA” reflected Berry Gordy’s hit-making obsession. However, Stax took a completely different approach.

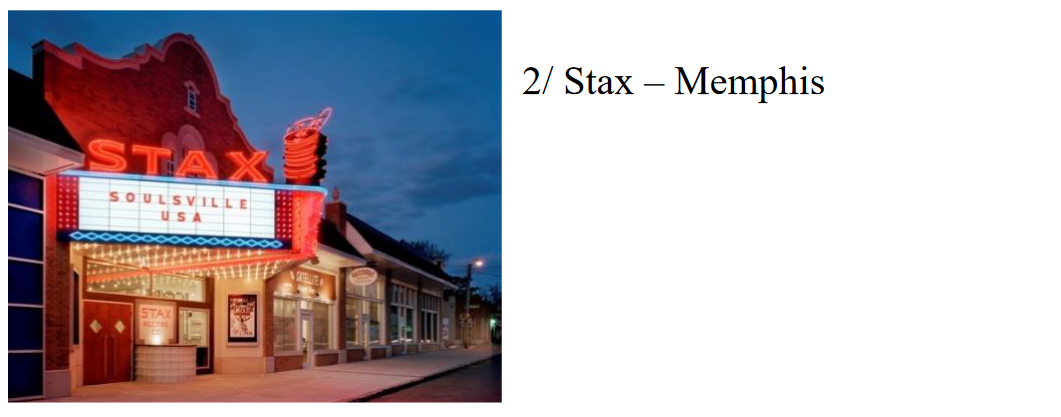

Stax: The Soul Alternative - Memphis

Notice it says “Soulsville USA”—a deliberate contrast to Hitsville.

Formed in 1959 as Satellite Records, renamed Stax in 1961 after the name was already taken. Founded by Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton (hence “Stax”). House band: Booker T and the M.G.s.

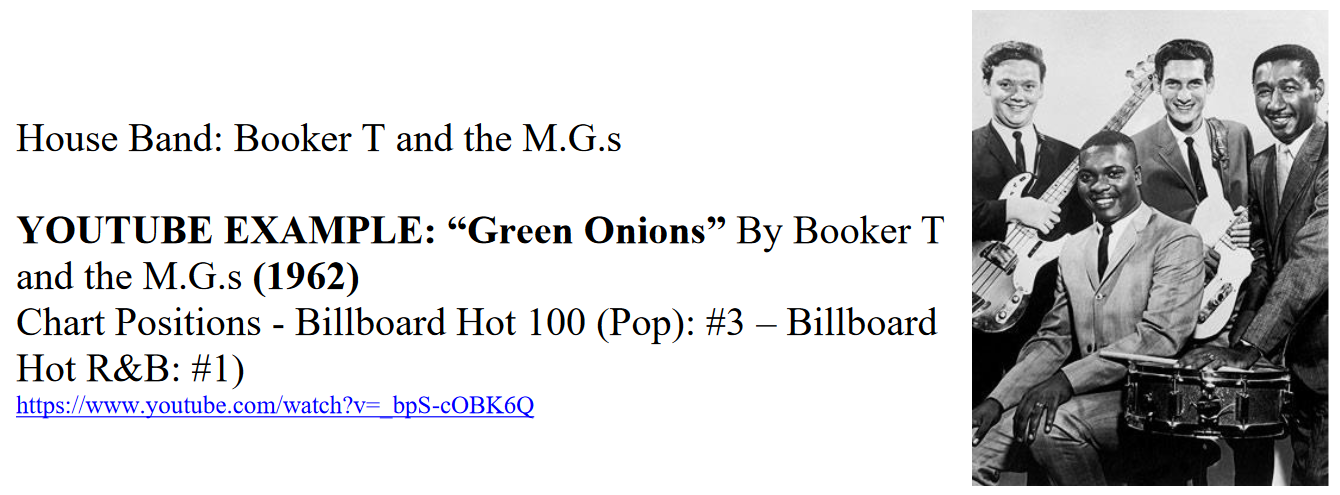

Booker T and the M.G.s

Unlike Motown’s invisible house band, Stax’s Booker T and the M.G.s received significant focus as an already-famous band in their own right.

Example: “Green Onions” by Booker T and the M.G.s (1962) reached Pop #3 and R&B #1.

The band toured independently, which occasionally created problems: with 2 black and 2 white members, they couldn’t eat at the same restaurants in the South (reference: Green Book).

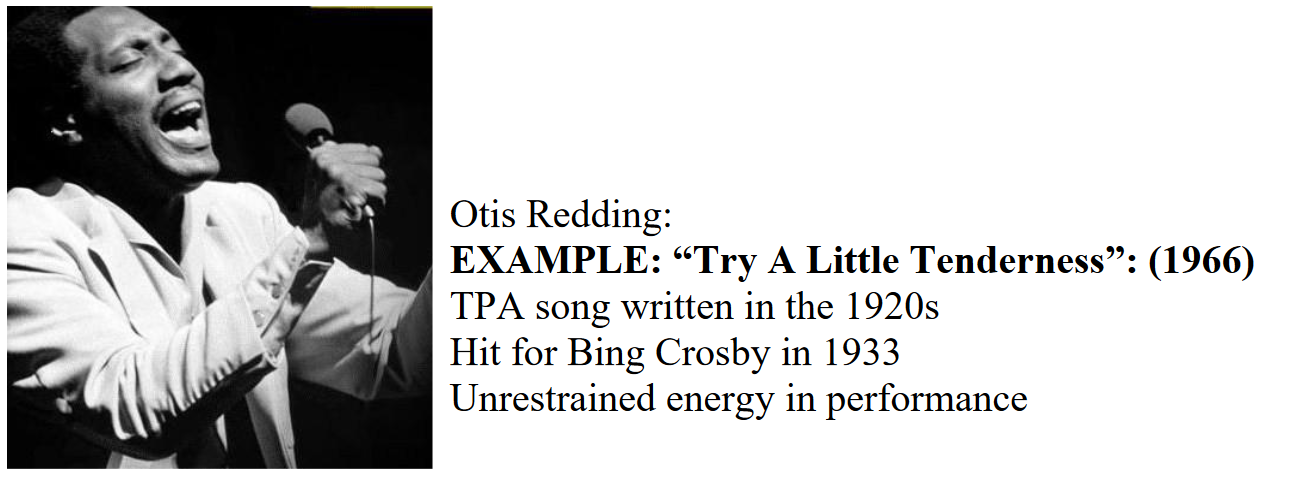

Otis Redding

Key Stax singer and decent songwriter who composed “Respect” (more on this later). Became popular with “Try A Little Tenderness” in 1966.

Originally a TPA song from the 1920s, it was a Bing Crosby hit in 1933. This particular backing band was actually The Bar-Kays, another Stax group. Unlike Motown’s complex background vocals, this featured just Redding himself with unrestrained energy.

Unfortunately, Redding died in a 1967 plane crash along with many Bar-Kays members.

Sound and Production at Stax

- No multitrack recording—crucial for everyone to perform together simultaneously

- No stereo recordings, only mono—because their studio was originally a movie theater with everything played through one big, leftover theater speaker

- Collective decision-making through voting

- Less arrangement emphasis than Motown (recording together made perfecting complex arrangements difficult)

- Stax artists made no effort at camera eye contact

- Focus on performance energy over accuracy—they wanted the best soul music regardless of hit potential. Hence “Soulsville USA”

- More significant Gospel influence than Motown

Example: Sam and Dave: “Soul Man” 1967

“Soul” became a term for black culture, not just a music style. This recording actually contained an error—the horn section missed a note—but was released anyway because energy trumped accuracy at Stax. Instead of making the band invisible like Motown, Sam and Dave literally talked to band members during recording.

Atlantic and FAME: The Third Center

1966: Atlantic begins working at FAME (Florence Alabama Musical Enterprises)

FAME was known as Muscle Shoals with house band The Swampers. Atlantic, uncertain about Soul production, sent numerous soul artists to FAME, including a significant signing:

Aretha Franklin

Originally a church singer, Franklin’s collaboration with FAME produced transformative results.

Example: Aretha Franklin: “Respect” 1967

Composed by Otis Redding as a minor hit about love relationships, Franklin’s version became the anthem for black rights and women’s rights movements. But when did this transformation occur? American history provides the context.

The Historical Context: Hope and Disillusionment

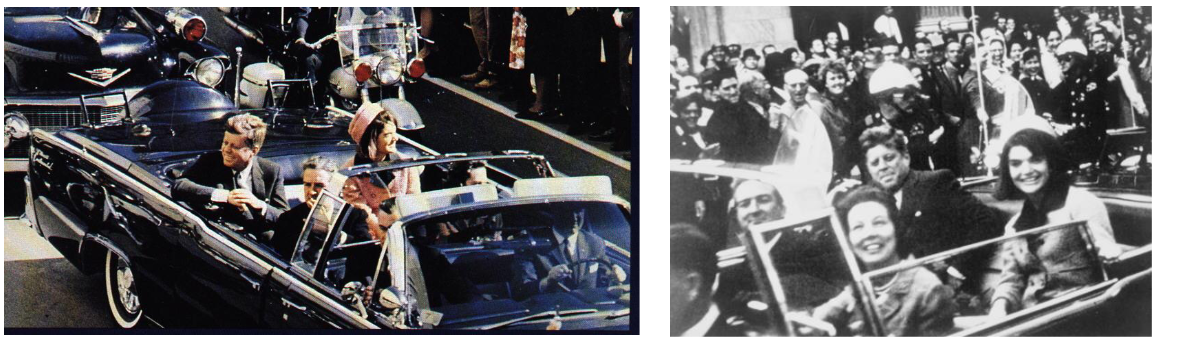

In 1960, John F. Kennedy’s election seemed strange: youngest president ever elected, Catholic (unusual), who brought tremendous optimism. Forward-thinking and supportive of Civil Rights, people called his presidency “The New Frontier” and “Camelot”—referencing King Arthur’s palace with its round table where everyone was equal.

Civil Rights Movement

1963: “I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King Jr.

Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, shattered the optimism he’d fostered. His successor wasn’t supportive of Civil Rights, frustrating Black Americans and leading to riots.

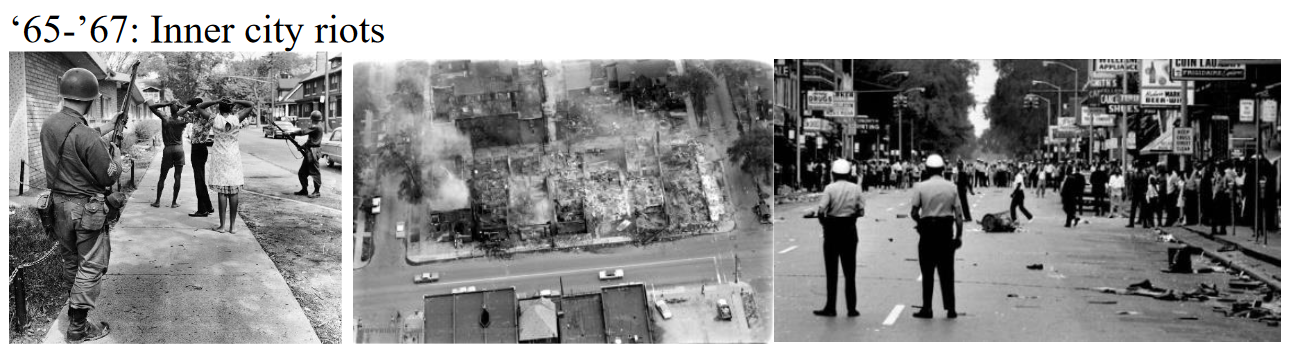

From 1965-1967, large, violent “Inner city riots” erupted.

Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968 marked another devastating loss.

Black Americans abandoned peaceful protest, forming groups like The Black Panthers. No longer wanting to merge with white society, they sought to develop a new “Black” identity: The Re-Africanization of Culture. This included keeping natural hair texture instead of straightening or wearing wigs, adopting traditional African names, and transforming music.

James Brown: The Godfather of Soul and Funk

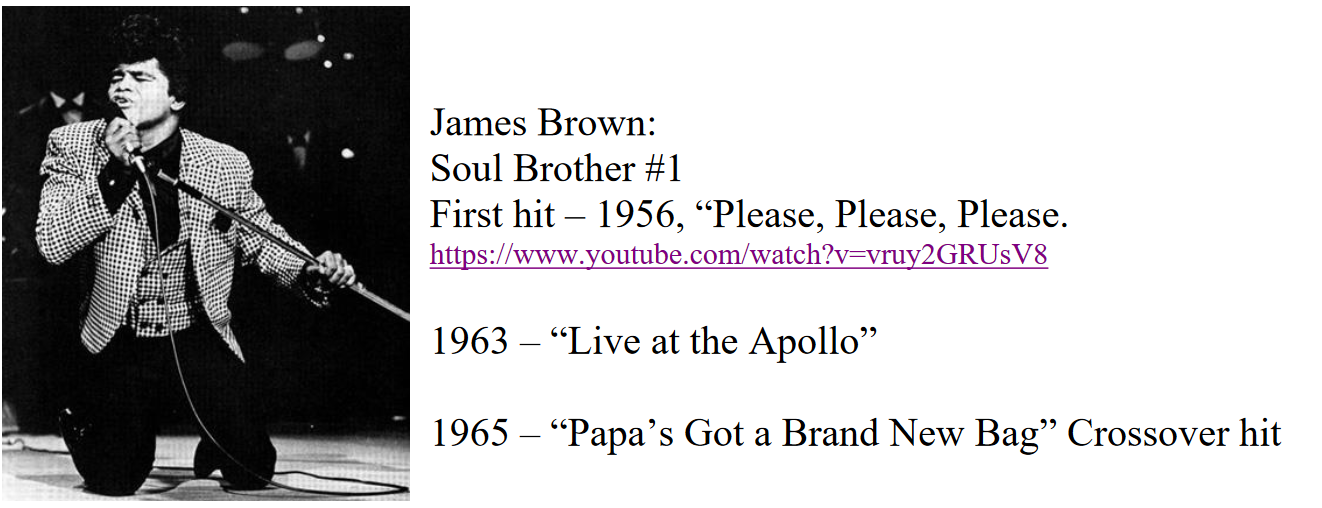

Massive early soul star nicknamed “Soul Brother #1”:

- First hit: 1956, “Please, Please, Please”

- 1963: “Live at Apollo”—first black album to sell over 1 million

- 1965: “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”—crossover hit

James Brown: “I Feel Good” (1965)

Pop #8, R&B #1 (R&B charts at this point featured mostly Soul, not traditional R&B). Popular with both black and white audiences because its structure combined 12-bar blues with AABA.

James deliberately chose this structure, explaining: “Black folks like blues, and white folks like something different in the middle.”

In 1965, responding to re-Africanization, James Brown decided music needed to change. This change was Funk (branching off from Soul while coexisting with it).

James Brown: “Cold Sweat” (1967)

Introduced Funk. Though “funk” wasn’t new (used in Jazz), its characteristics are better demonstrated in:

James Brown: “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine” (1970)

Funk Characteristics:

- Deprivilege of melody and harmony:

- No clear melody, less importance placed on melodic content

- Very little chord change—essentially one chord throughout

Privilege (focus on) Rhythm

- Interlock groove:

- Each instrument plays repetitive patterns that create complex sounds when combined

- Inspired by New Orleans/West Africa—James Brown’s perception of West African drum ensembles

- Though not entirely accurate, he captured the West African sense of community with a master drummer counting everyone in

- Cyclical structure—pleasure in repetition:

- Forms the interlock groove foundation

- After groove establishment, master drummer solos on top (James Brown’s role)

- Open-ended forms—cyclical vs. linear:

- Instead of linear AABA or 12-bar blues structures, based on repeated, cyclical, self-contained patterns

- Similar to riff-based composition reflecting West African influence

- “The One”:

- Since patterns can become complex, entire band emphasizes first beat of each cycle

- This emphasis on “The One” keeps everyone synchronized

Legacy and Impact

Soul and Funk represented more than musical evolution—they embodied the struggle for civil rights, black identity, and cultural expression. From Motown’s crossover appeal to Stax’s raw authenticity, from Aretha Franklin’s empowering anthems to James Brown’s rhythmic revolution, these genres provided both soundtrack and voice for one of America’s most transformative periods.

The music reflected the times: Soul’s optimism during the early Civil Rights movement, and Funk’s more complex, rhythm-focused approach as the movement evolved and black identity became more assertive. These weren’t just new sounds—they were declarations of independence, creativity, and cultural pride that continue resonating today.

The Folk Revival: From Politics to Poetry

Folk music is 民间音乐—music made by people who don’t do music for a living. However, some professionals began playing this style as their career. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, many teen fans of Rock ‘n’ Roll’s golden age were now in their early 20s. In universities, they sought more “serious” music: some turned to classical, others to folk.

But why is it called a revival?

Pre-WWII, folk musician Woody Guthrie was very political left. Folk musicians in general lean political left. His guitar bore the message “This Machine Kills Fascists”—calling it a machine like laborers, farmers, and miners use, aligning himself with workers.

Example: The Weavers: “This Land is Your Land” (Woody Guthrie, 1940)

- Political song against land privatization

- One member, Pete Seeger, pioneered many banjo techniques

- Folk instruments: banjo, acoustic guitar, harmonica

- Professionals who purposely don’t “show off”—self-conscious but deliberately focused on the song itself

- Successful from late 1940s to 1952

- “Blacklisted” in 1952 due to left-wing connections

HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) and McCarthyism (1947-1956)

Fear of communism in the U.S. led to a “witch hunt” for communists led by HUAC and Senator Joseph McCarthy. Folk artists, protesters, and labor groups were banned due to left-wing associations.

In the late 1950s/early 1960s, baby boomers in universities wanted “serious” music. Folk fit perfectly because it tells stories (including this story about communist witch hunts). The music industry recognized this trend, and younger folk musicians began appearing. Baby boomers loved musicians who looked their age.

Example: The Kingston Trio: “Tom Dooley” (1959)

By The Kingston Trio/Peter Paul and Mary—who looked like boomers their age. Similar to earlier folk music but with smoother vocals, more “produced” and “arranged” sound tailored to boomer audiences.

The more traditional folk was carried on by a new generation of singer-songwriters, including:

Bob Dylan: The Voice of a Generation

Woody Guthrie was his idol. Active 1961-1965. Born Robert Allen Zimmerman, he took the stage name Bob Dylan—”Bob” was just Bob, “Dylan” from his favorite writer’s first name. Unlike non-traditional folk musicians, he wrote his own songs.

Example: “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” (1962-1963)

Simple music with complex lyrics following a pattern using numbers, each verse beginning with:

“And what did you

___, my blue-eyed son?

And what did you___, my darling young one?”

This lyrical style resembles Biblical or fairy tale language, making the song feel ancient. Heavy metaphorical content—Dylan claimed it was a “bleak commentary on contemporary media,” but people believed it referenced Nuclear war, relating to the  Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). Americans discovered USSR missiles in Cuba that could reach the U.S. in 10 minutes. U.S. forces mobilized to Cuba—WWIII almost began.

Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). Americans discovered USSR missiles in Cuba that could reach the U.S. in 10 minutes. U.S. forces mobilized to Cuba—WWIII almost began.

Bob Dylan and Folk Rock

The Beatles called Bob Dylan the best songwriter of the time—they influenced each other. During the Newport Folk Festival (1965), Dylan played Rock ‘n’ Roll with electric guitar. Audiences hated the electric guitar but more importantly the Rock ‘n’ Roll that seemed inauthentic to them. Pete Seeger covered his ears. This event became known as “Dylan Goes Electric.”

Dylan fused meaningful lyrics with Rock ‘n’ Roll sound, creating “Folk Rock.” He lost folk fans but gained broader popularity.

Example: Bob Dylan: “Like a Rolling Stone” (from Highway 61 Revisited, 1965)

Fusing folk’s lyrical depth with 60s pop and rock sounds. Reached #2 Billboard Hot 100 / #1 Cashbox Top 100.

Bob Dylan’s Folk Rock influenced the broader Counter Culture movement.

The Counter Culture: Searching for Alternatives

In the late 1960s, the Counter Culture encompassed many movements. Essentially, it represented large numbers of young baby boomers seeking different life structures from their parents—looking to live experimentally rather than simply accumulating material possessions.

Influence of The Beats

A group skeptical of the U.S. government, including notable figures Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. Called “The Beats” because:

- Jazz was popular (Jazz Beat)

- Getting arrested or watched (“Beaten down”)

- They believed everything lacks free choice, requiring conspiracy theory awareness. To achieve true free will, you need to reach a higher mental state called “Beatitude”

In the early 1960s, young people grew skeptical of government, organized religion, and their parents’ ideologies. The coolest, most fashionable people were called “Hippies.”

Two main hippie centers: Greenwich Village (New York) and Haight-Ashbury (San Francisco). Hippies valued experience over material goods and community over individual.

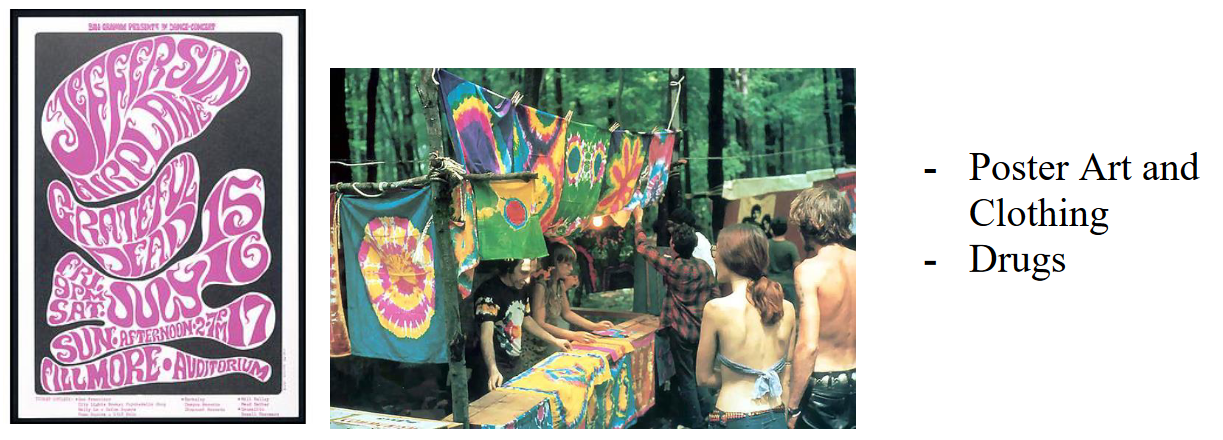

Focus on Sensory Stimulation: Psychedelic Experience

Abstract posters and clothing created “Psychedelic experiences.” Drugs were used to “experiment with new states of consciousness.”

Music for Hippies:

- Loud: Music appeals to hearing, but played loud enough, you physically feel it—appealing to two senses instead of one

- Concerts utilized theater lights for lighting shows alongside music, appealing to visual senses

- Longer or unusual song forms: AABA and 12-bar blues were good but predictable; customized, longer structures created more surprises

- Jamming (collective improvisation): Even more surprises, all aimed at reaching unusual, psychedelic, higher mental states

Example: The Grateful Dead: “Truckin’” (1970)

Influenced by Bob Dylan. While they recorded albums, their concerts were different:

- No pre-planned setlists

- They’d play songs similar to album versions until the end, then continue jamming for extended periods to create psychedelic experiences

- Since every concert differed, fans called “dead heads” followed their tours, hearing the same songs played differently

- One 1972 concert extended 17 minutes after a song

- Loose arrangements typical of folk rock

However, Counter Culture wasn’t a music style—counter culture people played all kinds of music. Apart from Folk Rock, others played Rock ‘n’ Roll influenced by The Beatles, calling their style:

Acid Rock / Psychedelic Rock

“Acid” referred to the drug. The Beatles’ musical experimentation, particularly “Tomorrow Never Knows” (1966), influenced other artists.

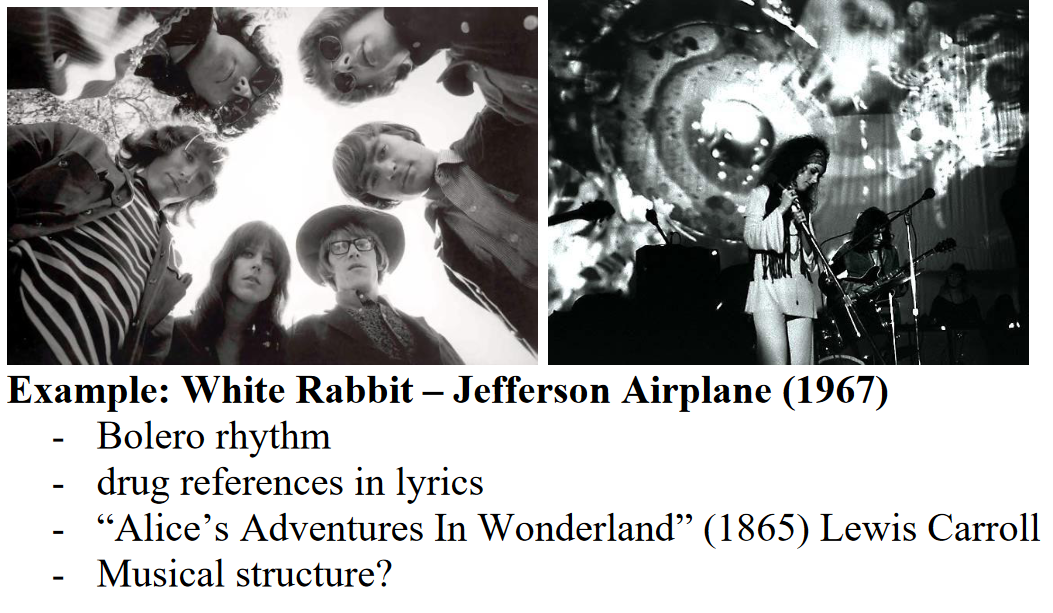

Example: Jefferson Airplane: “White Rabbit” (1967)

Counter Culture artists usually didn’t aim for big hits, preferring experience. However, this was a major hit. Though Counter Culture songs were usually long, this was relatively short.

The rhythm based on Spanish dance rhythm Bolero. Drug references filled the lyrics, which also related to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1865) by Lewis Carroll. The Counter Culture believed reality was fake, requiring seeing the real world—similar to Alice entering wonderland through the rabbit hole. The Matrix also references Alice’s Adventures.

Musical structure: Nothing conventional—structure followed volume increases. Started quiet, grew louder, ended at highest point. Like taking drugs, where effects start slow and gradually intensify.

The west coast counter culture peaked during the summer of 1967, remembered as the Summer of Love.

Political Awakening: From Inner to Outer Focus

After 1967, Youth Culture became more outward-focused:

- More politically active

- Focused on Civil Rights and Vietnam War Draft

- Increasingly skeptical of government

Youth International Party (Yippies) formed with leaders Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman.

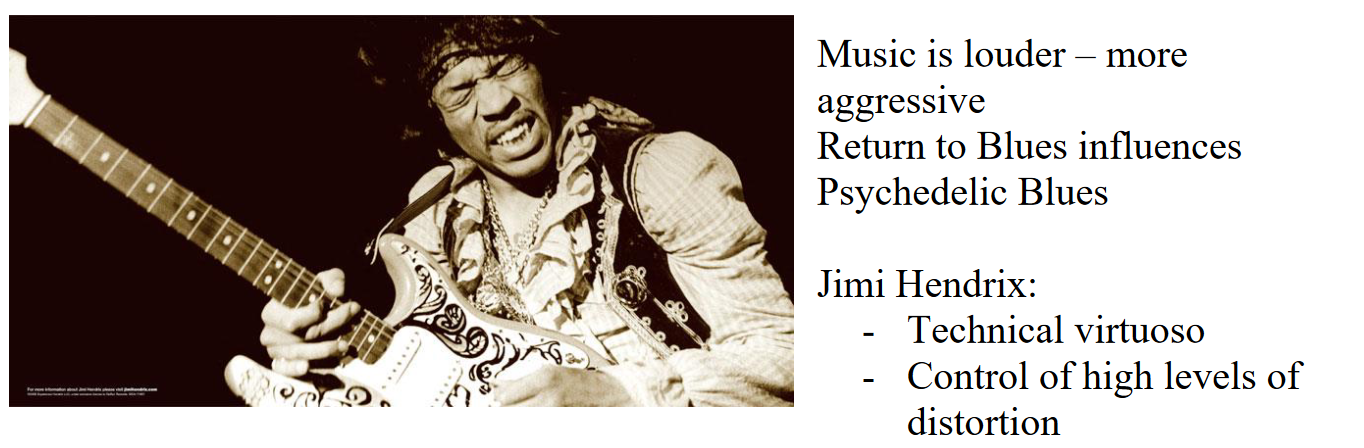

Instead of Grateful Dead or Jefferson Airplane’s folk rock influence, music became more British blues influenced, called Psychedelic Blues. The definitive artist:

Jimi Hendrix: Guitar Revolutionary

Technical virtuoso able to play smooth melodies with high distortion (full amplifier).

Example: Jimi Hendrix: “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” (1967)

- Clear Blues influence—not 12-bar blues but a-a-b lyrics pattern

- Pioneered “Wah-Wah pedal”—ground device changing guitar tone as you pedal

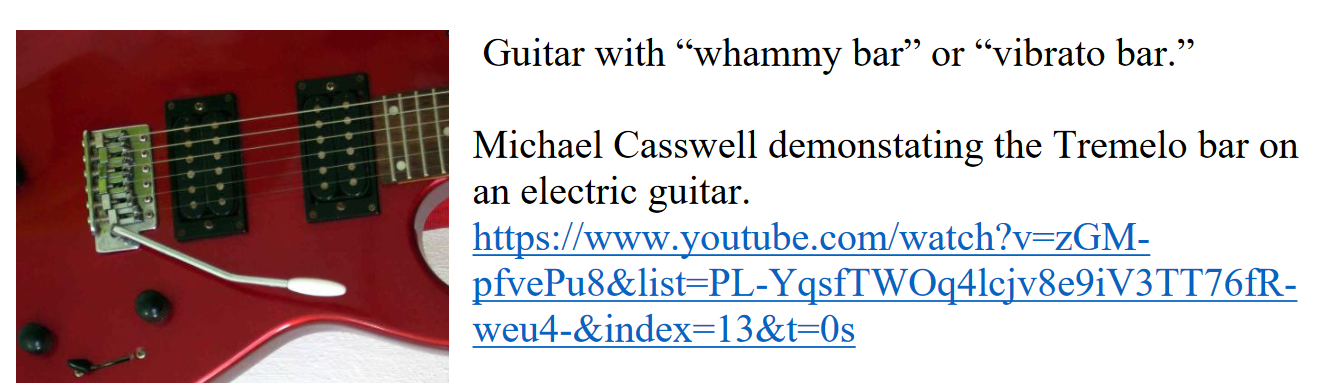

- Whammy bar—first rock player using it aggressively

Sliding it changes string tension, altering pitch.

Woodstock and Altamont: The Rise and Fall of Idealism

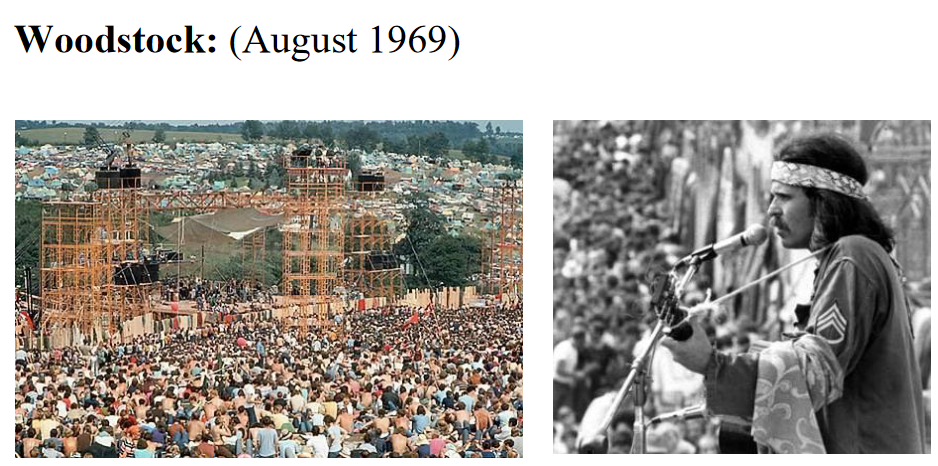

Woodstock (August 1969)

A counter culture concert on a working farm. Overwhelming attendance could have been disastrous due to lack of organization and potential stampedes. However, it triumphed because counter culture valued community over individual—everyone helped each other stay calm and safe (except 1 death).

This massive success proved counter culture could work, making people believe it could change the world.

Video Example: Country Joe performing Vietnam protest song, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die Rag”

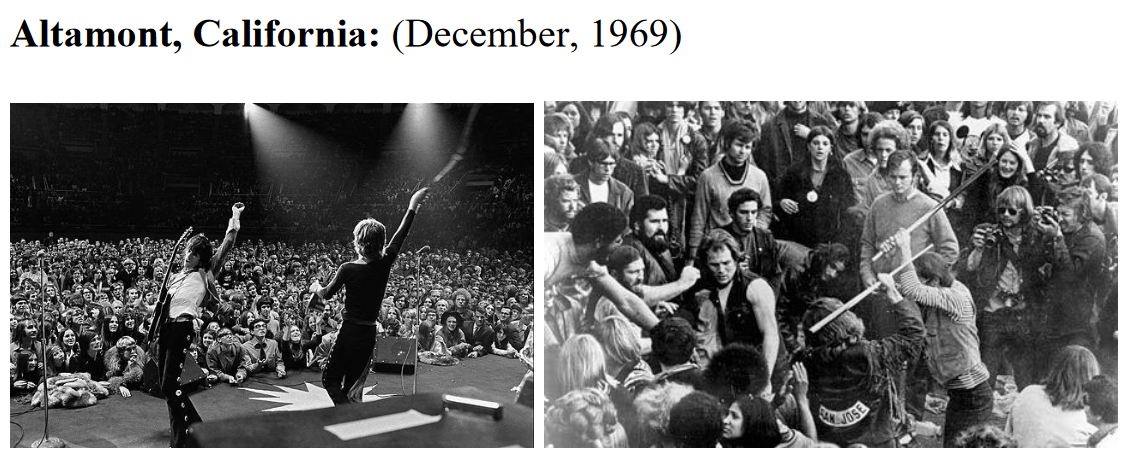

Altamont, California (December 1969)

The Rolling Stones, having declined Woodstock, wanted their own version after its success. Two crucial differences from Woodstock:

- Space: Woodstock expanded across farm fields; Altamont was enclosed stadium with crowded, anxious conditions

- Security: Rolling Stones, embracing their “bad boy” image, hired Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, paying them with beer

Hell’s Angels carried weapons, beat people, and killed someone. Since Rolling Stones wanted to record like Woodstock, they captured a Hell’s Angel murdering someone on camera.

This created horrible imagery for counter culture. Youth who believed counter culture could change the world were devastated.

April 1970: Paul McCartney leaves The Beatles—they break up.

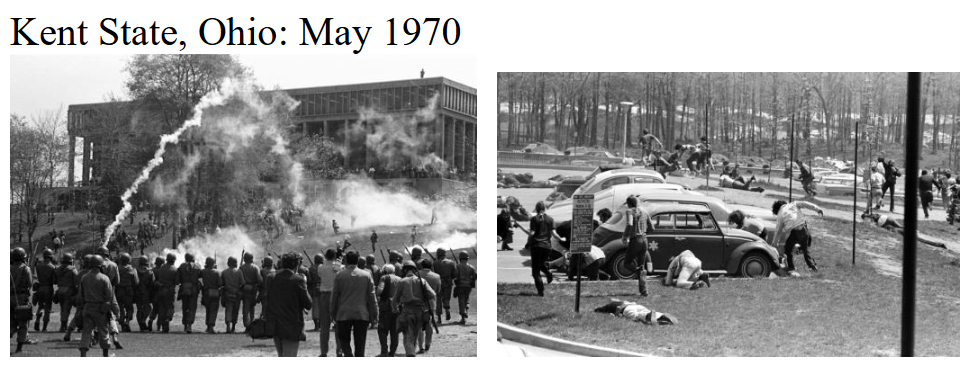

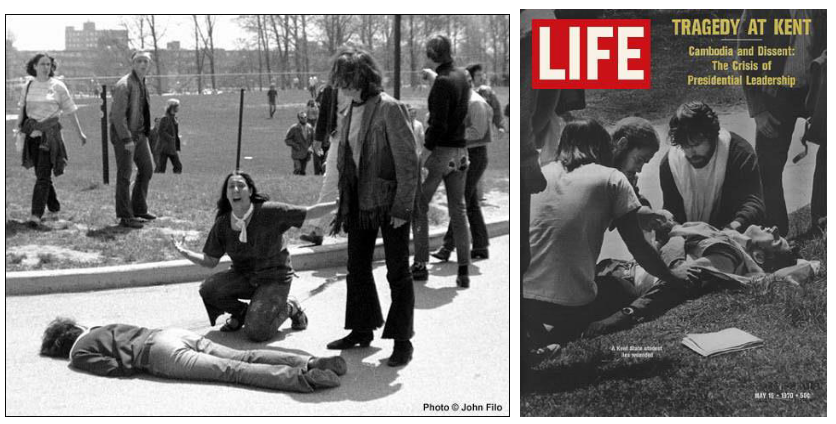

Kent State, Ohio: May 1970

Young people protested the Vietnam War, believing they shouldn’t fight. At Kent State University protest:

- First day: peaceful protest

- Second day: vandalism started, National Guard arrived and opened fire on students—some injured, some died, including non-protesters

Counter culture cooled down. Youth realized counter culture ideals couldn’t change the world.

Song about this: Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young: “Ohio” (1970)

September 1970: Jimi Hendrix dies

October 1970: Janis Joplin dies of drug overdose

July 1971: Jim Morrison (The Doors) dies

The 1970s: Cynicism and Diversification

Counter-Culture’s failure initiated a shift toward more cynical (愤世嫉俗) worldview. Many young people no longer believed they could change the world or in counter-culture ideals (community over individual).

This cynicism was reinforced by:

The Energy Crisis (1973-1974)

Yom Kippur War (October 1973): Israel fought countries supplying U.S. oil; U.S. supported Israel, lost oil access. The Energy Crisis marked the first economic recession since WWII’s end.

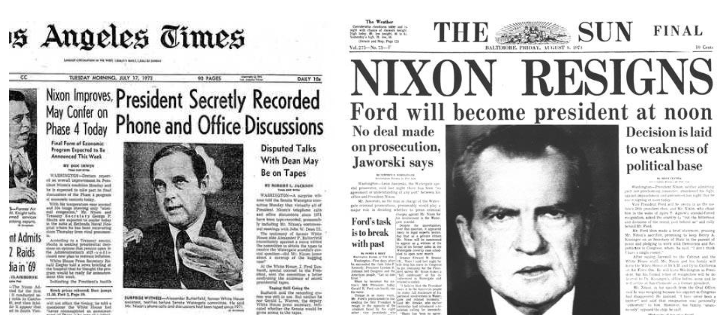

Watergate

Facing criminal charges and impeachment, President Richard Nixon resigned (August 1974).

Vietnam: The Fall of Saigon (April 30, 1975)

The U.S. lost the Vietnam War. U.S. and non-communist Vietnamese troops trapped in Saigon had 24 hours to escape via helicopters.

Musical Evolution in the 1970s

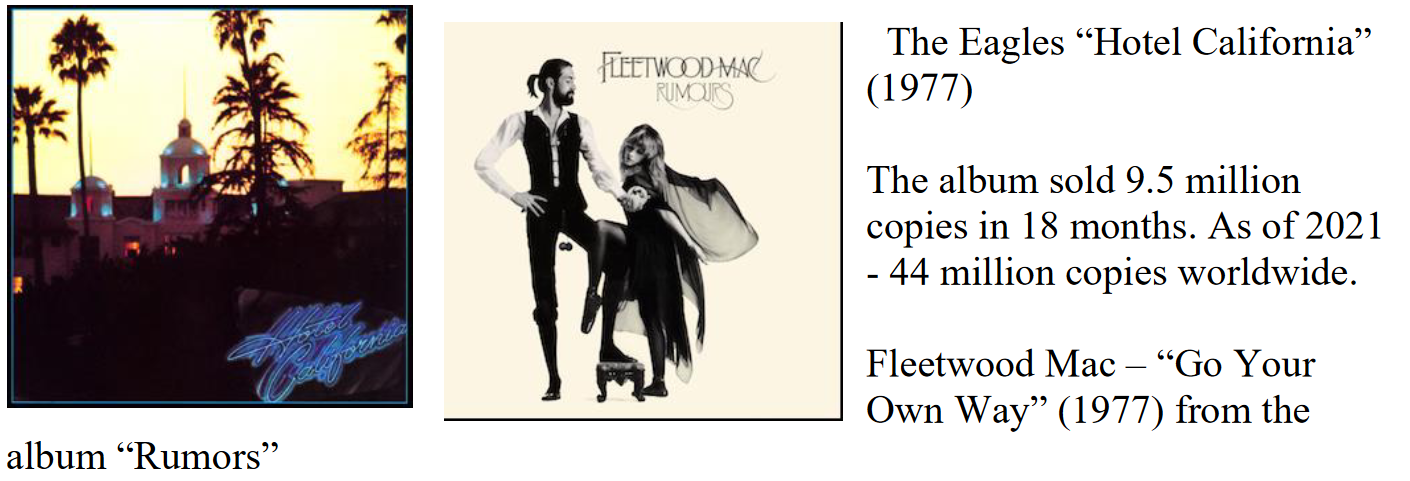

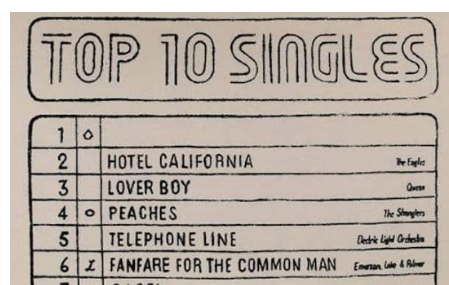

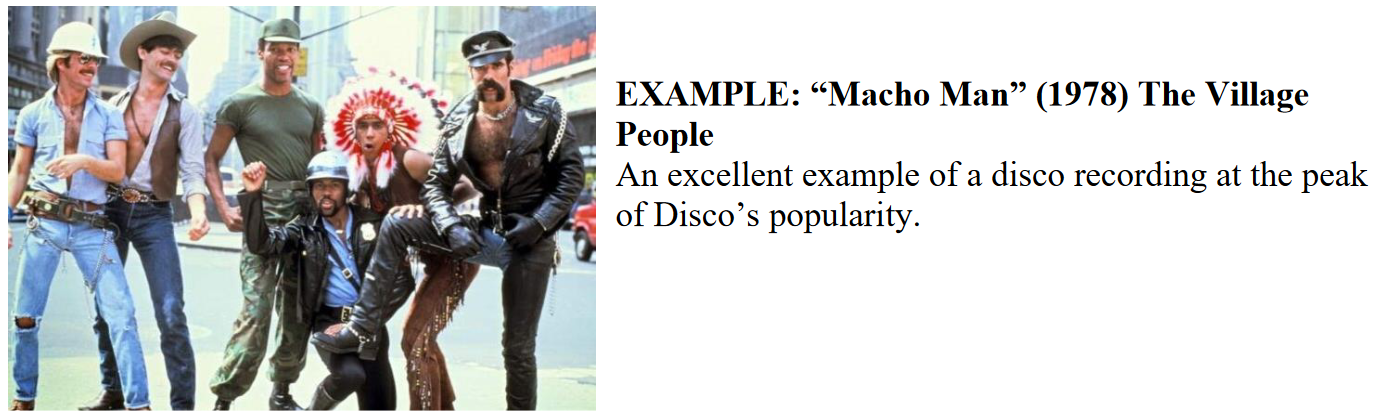

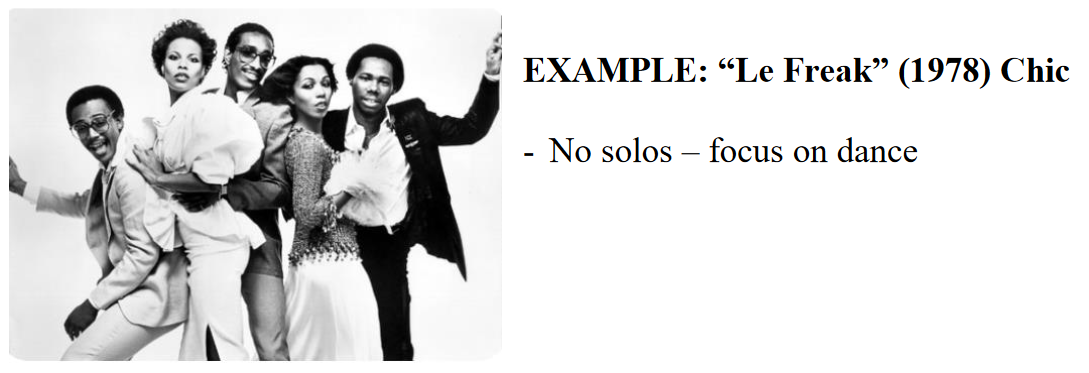

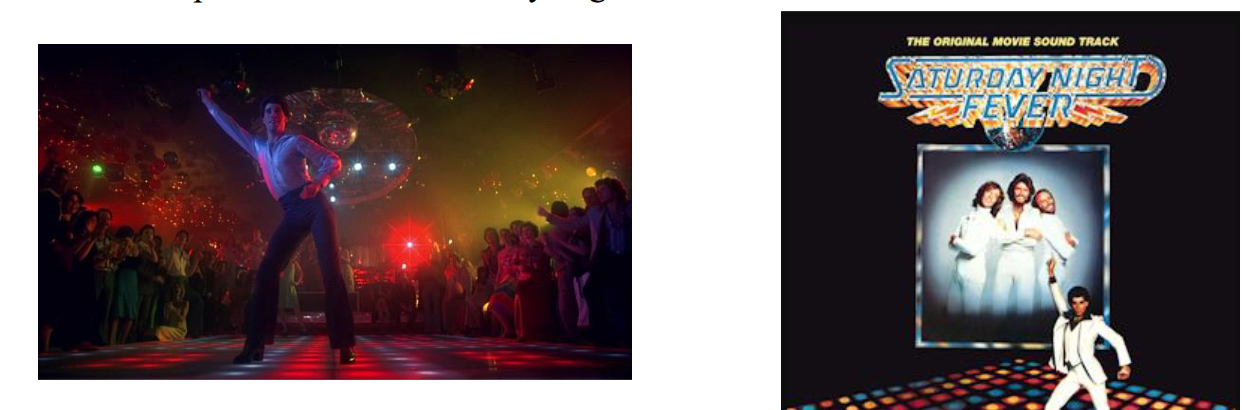

For Soul Music: